general peculiarities

I love the 1953 movie Invaders from Mars. No, I did not see it at the movie theater (I was only one when it came out), but I watched it fourteen times in one week on Channel 9's Million Dollar Movie on our old black-and-white television set. The martian leader (a part octopus, part grey-glossy head inside a glass orb) was pretty darned scary; it might still be in 2015 (as I write this). However, the plodding mutants who did the leader's bidding were, frankly, stupid. Oh, they looked good enough from the front, but when they moved away from the camera, it was clear there were zippers on the rubber suits they wore.

That sort of spoiled the illusion.

This is what distinguishes (most) drama (whether on stage or on the large screen or the small screen)--drama is an audio-visual form. That difference makes us consider drama differently from other forms of literature. For one thing, a book is an active medium for the reader, and a film is a passive one.

wait! what? that makes no sense!

In France the movie director (and sometimes the producer) is said to be responsible for la realisation d'un film. In other words, the filmmaker makes the film real for the audience.

Is that a good thing? a bad thing? It is definitely a thing. Consider the implications:

barring individual quirks (differences in eyesight, hearing, attention, projector glitches for instance), everyone who sees Furious 7 sees the same thing. The muscle car Vin Diesel (Toretto) drives is a 1970 Dodge Charger. It will always be a 1970 Dodge Charger. If an audience mistakes it for a Prius, well, I don't know how to respond to that, but it is a 1970 Dodge Charger. The filmmakers (various roles) create the setting (location), the costumes, the camera angles, the sound effects, the props, possibly CGI, the edited cut(s) with background music, and so on. So when I go into the Dine-in Theater, I sit and RE-LAX. I don't have to do any work; it's all been done for me.

When I read a book, I do all the work. I have to imagine what things look like and just how scary/thrilling/romantic/funny something might be. I cast the piece in my head (personally, I often cast actors in the roles in my head, but I have seen A LOT of films). I have to imagine how the dialogue is paced and pitched. It's a lot of work. And I even sometimes have to stop to look up words to figure out what in heck the author is talking about.

So a film could certainly be "better" than a book, and (as is often said but not always the case) the book can be "better" than the movie.

Two examples to consider:

Stehen King's Cujo--the monster dog who terrified readers in 1981, appeared in a 1983 film version, and the terror vanished. While reading, that monster St. Bernard can turn into a ravenouos, rabid hell hound, getting creepier and creepier as the reader reshapes it in the mind. On the screen, Cujo is a big, floppy, slobbery, cute St. Bernard. Yes, he barks a lot, but you just want to hug him. The book works where the movie fails.

Furious 7: that would lose SO MUCH as a book. It is all car chases and explosions; it is audio-visual overload. Like Avatar (that makes three examples, I know), the movie is bound to be better than the book because it's strengths are the strengths of sounds and sights. HOWEVER, if James Cameron had not had his mega-budget to recreate a Halo-like universe in Avatar, it would likely look cheesy, like the monster at the end of Cloverfield (yes, that's four examples; stop counting!).

but what about plays--Shakespeare and all that?

The difference between films and live theater is (generally) striking. The history of "drama" is filled with clever technological gimmicks to create the illusion of reality. The Collosseum in Rome was sometimes filled with water, and pitched naval battles took place to entertain the crowds. 19th-century England featured a play with an on-stage horse race (that took place on a massive turntable; it was very dangerous).

More often than not, budget and space restrict what can be realised on a stage. Quite often, a few flats are used to suggest a scene (when Shakespeare's characters moved from, say, the city to the woods, a single tree was placed on the edge of the stage, and audiences knew, "AHA! We are in the woods now." Sometimes plays are performed with bare stages, and what the actors say/do suggests what the audience should be seeing. In this case, the audience is asked to do some of the work while other elements (the actor, the voice, the costume, the lighting) are made real in front of the viewers.

This puts live plays somewhere in the middle with the written word (requiring the most work from the reader) on one end and the film (requiring the least work from the audience) on either end.

That is not to say books are hard and plays are sorta-hard/sorta-easy and movies are easy. Some books are really easy; some movies are really hard. Both can be said of plays as well. Here are examples of each (feel free to disagree, but you should still get the idea):

Books: Stephen King's Under the Dome (easy) / Haruki Murakami's 1Q84 (hard)

Plays: Allers and Mecchi's (and several composers) The Lion King (easy) / Luigi Pirandello's Six Characters in Search of an Author (hard)

Films: James Wan's Furious 7 (easy - I can't get enough of it) / David Lynch's Eraserhead (hard)

don't ignore the differences, but don't be fooled by them

THIS IS AN IMPORTANT POINT: All of the elements we looked at with the story is still relevant in a play. We still look for patterns and peculiarities. Plays and films may have significant setting, character, plot, symbolism, etc. to consider. However, in addition, we need to consider staging--the audio-visual elements that are produced for a live audience. How would you, for example, produce a small play in a small venue which required at least one actor to be delivering her lines while in the water?

A final reflection: (easy) and (hard) do not = (good) and (bad) or vice-versa. They may relate to what some English teacherc consider popular vs. literary, but I don't make that distinction. They certainly do relate to "I can soak up the plot and go along for the ride...wheeeeeee!" vs. "Hmmm...what's going on here? This will take some thinking." Personally, I like both. But if I had to write and analysis (exploring ideas, not just giving personal opinions) about something, I would probably pick something a bit harder and thought-provoking; it would give me much more to write about.

modern theater - "Trying to Find Chinatown"

This week's reading includes two modern one-act plays. As you can imagine, a one-act play is not likely to generate a lot of ticket sales; they are often produced in colleges and universities or at small and/or experimental theaters. As a result, they are typically low-budget productions. To make up for the lack of large venues and abundant funding, these plays are often staged with minimal sets, little technology (lasar light shows are expensive), and more suggestion than realism.

Really, what is absolutely necessary for David Huang's "Trying to Find Chinatown"? Not much. You might want the suggestion of a street corner, but it could easily just be performed on a blank stage instead. The dialogue lets us know where we are. An electric violin would be nice, and some Hendrix playing over a loudspeaker is in the stage directions. Beyond that, the weight of the play is carried in the dialogue (and Ronnie's monologue at the end).

and "The Cuban Swimmer"

Since you will be focusing on Huang's play for this week's discussion, let's focus on Milcha Sanchez-Scott's "The Cuban Swimmer." It really has more staging consierations anyway. It lends itself to more "How would you do this?" and "Why?" questions.

First, there are some problems/challenges to think about:

How do you show someone swimming for twenty-or thirty minutes? If she were really in water (on a tank on stage), she would get tired; the audience would not hear the lines; she might drown.

How do we show the family in a boat? If we did the play at the YMCA pool, the sound would distort, and the actors standing in a canoe-sized boat in the pool would probably tip over and turn the play into a slapstick comedy.

How do we get a helicopter on stage? A drone or remote-control helicopter might work, but the actors would be distracted if they were being buzzed by flying toys

How do we show Margarita surviving many minutes dragged down to the bottom of the sea? That's not even possible.

Maybe film could save us. We could actually film live actors in real boats and helicopters, edit carefully, add the sound later. But would this really be an interesting film? Not much happens to develop a movie version.

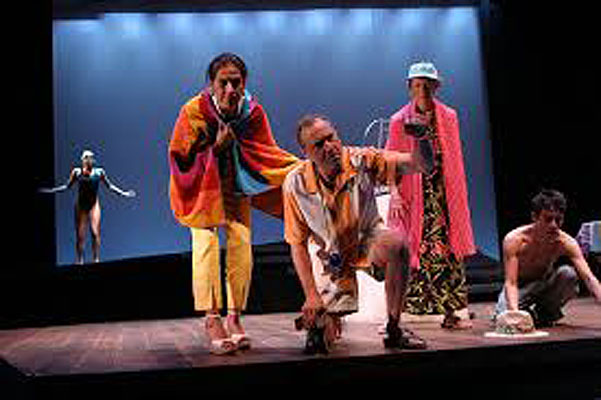

The student production shown in the image at the top of this page offers several solutions--make simple props that SUGGEST ocean waves; create a flat with the silhouette of a small boat for actors to stand behind, have a large, old-fashioned radio for us to hear Mel and Mary Beth over the air waves. The cost is low, but the audience has to be willing to "suspend disbelief" (that is, for the amount of time they are watching the play, audience members have to pretend it is a boat in the waves and so on. Fortunately, audiences often do suspend disbelief; the alternative is to just be grumpy and have a miserable time. Besides, sometimes the simple solutions that theater companies come up with are pretty creative, and audiences often appreciate ingenuity. In one production of "The Cuban Swimmer," for example, the illusion of the helicopter was created by a light shining down through a ceiling fan (out of view of the audience); the shadow fell on the actors, and a soft "Whump, whump, whump" came from a speaker. Clever!

Here are two solutions to the "under the sea" segment:

It actually looks pretty striking in black and white; I'm not sure how to do that completely (lighting, make-up, costumes could get you close).

Margarita, in a position suggesting she is swimming, is surrounded by actors in (I am guessing) dark blue or black costumes. Each is holding a sea creature suggesting that Margarita is being surrounded by sea life as she has been dragged to the bottom of the ocean. The photo probably should not show the faces (why are they all smiling?); the dark costumes should fade into the darkness (representing water where little light reaches the bottom). I would work on that a little; however, the relative positions of Margarita and Eduardo are striking.

Papi is not literally on a boat (he is standing in a raised seating area with a tight spotlight on him), but he could be. He is far above Margarita, and we sense his fear and anger as he is shouting but unable to help his daughter daughter who is quite-likely drowning.

They are in separate pools of light with darkness between. Father and daughter (coach and swimmer), so close to one another are now both on their own.

An interesting feature of this second version, which is on a more-conventional stage, is that the family is agonizing and searching for Margarita over the edge of the boat (over the apron of the stage). Margarita is behind them.

That is doubly effective. First, she can stand in front of the blue-lit screen upstage (up means away from the audience). Second, in an odd reversal, she is higher (not lower) than the family which allows the audience to see her even though she is smaller (farther away) and surrounded by blue. The point is; they are separated, and no matter how long the family looks for her, they are not going to see her the direction they are looking.

Both solutions are easy to recreate, and both insure the actress playing Margarita can deliver her lines clearly, without drowning.

why this play may be particularly well-suited to this

Using symbols to suggest things that they literally are not (blue light is not literally an ocean; a cardboard cutout the shape of a boat is not literally a boat; a ceiling fan is not literally a helicopter) reinforces the fact that this play operates on two levels:

There are actually open water swimming competitions off of San Pedro, around Catalina, up and down the coast.

The title and the travel over the ocean between mainland and island (island and mainland) is suggestive of trip some Cubans have made to places like Dade County, Florida to find a life with few opportunities.

Many things in this play operate symbolically:

Papi is leading them, like a father (head of a traditional family) who will work in the U.S. to give his family greater opportunities.

Different amounts of English/Spanish are spoken by different characters. Eduardo is about 50:50 (he will need English in the workplace, but he needs to be able to communicate with abuela. She, in turn, speaks no English, and would probably rather be back in Cuba where everything she knows is. Simon speaks English, almost exclusively. He is the next generation, the one raised in the U.S. with English being spoken by his friends and classmates. Note also the different amount of English/Spanish spoken by males and females from the same generation (why does Margarita speak more Spanish than Simon?); I will let you wrestle with that.

Margarita is out of the boat; she is racing towards some goal. As a woman in Cuba, would she have had the opportunities for education and career she does in the U.S.? Is it harder for her as a woman because the traditions she was raised in expect her to become the next mami? Simon gets a free ride in the boat (he is expected to go to school and/or work). The good news is, even though the race almost defeats her, she miraculously (walking on water) WINS! It is a very hopeful play :)

Mel and Mary Beth, on relatively equal levels with one another, are above all of this. This is the home they know and are comfortable with. They don't have to struggle to acculturate. They also do not really understand the struggle of the family in the boat/sea below them; they stereotype.

Suggestive/symbolic staging actually parallels the symbolism that operates on one level of the play.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)