"cobwebs to catch flies"

There really is a difference between picture books, picture-story books, and illustrated books, but I'm using the term picture book to refer to them all here.

The difference really has to do with the ratio of picture to text. Picture books have few if any words; they are often concept books for very little children, or they may just be soothing bedtime stories, such as Margaret Wise Brown's classic Goodnight Moon (which I have memorized from having read it a zillion times!). Picture-story books, like the wonderful Frog and Toad books by Arnold Lobel, have more text; they are often intended for early readers (Frog and Toad happens to be part of the "I Can Read" series). Illustrated books are "chapter books" which have occasional pictures. Both Alice and Wonderland and The Wonderful Wizard of Oz are two examples.

Most of what we think about in this category are books for younger children--picture and picture-story books, and there are many, many to choose from. As with most things, some have more to offer than others. I'd rather not enter a discussion of "better" and "worse" books here; ironically, many of the books children hold as their favorites would be in the "worse" bin (*sigh*). I'll just stick to a brief look at how some books are richer than others.

Two favorites in the how-can-we-cause-eye-strain genre are the Where's Waldo books (often imitated) and the I Spy series.

The books are fun.

The inherent problem with both series is the lack of repeatability. Once you've located Waldo on the page, you're done with that page FOREVER. The I-SPY books are more challenging, and occasionally there are mysteries in the back of the book that extend the book a little, but, again, once you've found four red flies and a king's wife and a blue eye on a page, you've done the page; it won't offer you anything new the next time through. Still, the I-SPY books are a little more sophisticated. If nothing else, they leave one wondering at the amount of time and painstaking effort the photographer went to to set up the elaborate and often inventive scenes.

Laurie Keller's Scrambled States of America and Open Wide have more going for them. The books have simple, creative stories: in Scrambled States of America Kansas, upset at always being stuck without an ocean view, convinces the states to switch places; at first the change is fun, but soon Florida gets too cold in Minnesota; Alabama, New York and Indiana are bothered by the earthquakes in California. There are also interesting sub-plots: Nevada and Mississippi meet and fall in love and are reluctant to go back to their original places (there's a charming image at the end showing the hearts of these states connected by a dotted line). Spread throughout the books are small incidental drawings that cause the reader to look closer. Unlike the "I found it!" response to finding Waldo in a crowd, the reader discovers an interesting fact or a joke or bit of sub-sub-plot; there's even a snapshot of Idaho winning a limbo contest.

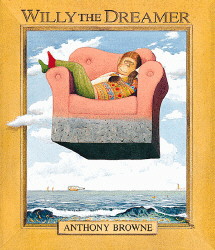

Another spin on this "look closely to discover more" can be found in Anthony Browne's books, such as Voices in the Park and Willy the Dreamer. Not only are Willy's dreams (in the latter book) interesting and suggestive of the sorts of dreams children actually do have (of becoming a rock star, of being a powerful monster, etc.), there are also little motifs that demand discovery on each page: where is the banana (does it form a microphone? the body of a flying fish?); how is the design of Willy's vest integrated into the picture? On top of this, Browne is a fabulous artist who pays homage to several famous (many surrealist) artists. In a classroom or at home the Browne paintings could be compared to the original works by Magritte, Dali, and others.

In general, the richer texts offer more. They can be read and re-read, and, often, the reader can discover more on each reading. At the very least, the most interesting picture books explore our world and human nature. The best, er...most successful, blend text and picture to suggest some theme that the reader can identify with.

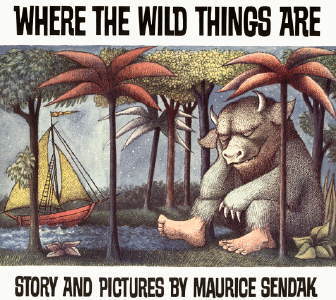

One of the most perfect marriages of text and picture and even page layout is Maurice Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are.

It's the sort of story that some parents object to: "For pity's sake! The book is encouraging kids to have a 'wild rumpus'!" But then there isn't a story in the entire genre that someone won't object to.

The story is simple. Max acts wild and is sent to his room. He exercises his wildness in his imagination and then comes back to his loving family.

Much of the story is suggested (shown) rather than preached (told). Max's wildness is defined by his wearing a wolf suit (he's in an animal state), hammering nails into the wall, chasing the dog with a fork, and by the monster-filled jungle that fills his room. In the real world he doesn't get away with his behavior--he shouts, "I'LL EAT YOU UP!" (there are a lot of eating references here) to his mother, and she sends him to his room without supper. In his room (in his imagination) Max is in control; he is able to tame the monsters, and (with a great example of psychological projection) he can send them to bed without supper.

The eating takes on greater significance when the monster's say to Max, "we'll eat you up--we love you so." Here the eating (like Max's challenge to his mother) is like a parent saying, "I love you so much I could just gobble you up"--eating, consuming, surrounding is equated with love and closeness.

The pictures are imaginative rather than literal. There are monsters, but not the sort that will scare child readers (I'm not too sure about adults though); they're more like mis-matched stuffed animals. The transformation from real to imaginative world is suggested by bits of Max's furniture turning into palm trees and vines. Even the wild rumpus is really just monster-sized kid play (climbing, jumping, making noise).

The relation of illustration to white space is also suggestive. While Max is in the world of his mother's control, the pictures are small, and the surrounding white margins huge. As his imagination takes over, the pictures push away the margins and even the text--there are six full pages of wordless pictures near the middle of the book, at the peak of Max's wild imaginings. As he starts to miss his mom and his dinner (it's the smell of food from far away that draws Max back), the text and margins come back. The final page, once Max has come back to find his dinner waiting for him, has no picture, just text: "and it was still hot." The immediacy of the hot food and Max's real physical hunger push out all the wild thoughts ... for now.

Where the Wild Things Are is a little book, but it is a thoughtful book that works on many levels. It is a prime example of one of the richer picture books.

![[course schedule]](button31s.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button31q.gif)

![[lectures]](button31l.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button31p.gif)

![[readings]](button31r.gif)

![[home]](button31h.gif)