reading, how to

Uh, that's obvious. You know how to read. You're reading this (I hope).

There are different kinds of reading, and in college/university, it's different from reading Mistborn by Brandon Sanderson or reading the box scores from the Dodgers/Rays World Series. You are reading for a purpose. What the purpose is varies: maybe you are reading instructions that you need to understand and follow for a physics experiment; possibly you are reading several articles on the causes of the Crimean War for a paper you are writing; perhaps you are trying to figure out what the most-important parts of your psychology chapter are so that you will do well on the upcoming mid-term; possibly you are trying to read a poem very closely to try and figure out what some of peculiar words and phrases suggest rather than flat-out say.

Rarely, if ever, are you going to have a college professor say, "OK, I want you to read A Catcher in the Rye and memorize the names of all of the characters in the book. There will be a test." That is just meaningless drudge work; it serves no real purpose (except, perhaps, to insure that you actually read the book, though we both know you are more likely to just memorize the Characters list from Spark Notes); what a waste of everyone's time, and no real learning takes place.

No, a professor is more likely to try to discover what you have learned, how you think/analyze, whether or not you can support a claim with actual examples. This is the sort of question that you are more likely to see on a test on A Catcher in the Rye (though, to be honest, that book is way too easy for college): "What is the significance of the title A Catcher in the Rye, and what does it reveal about Holden Caulfield? Be sure to quote and cite examples from the book that show this." That is quite a bit more work, and it involves analytical thinking.

An American History professor might ask you to outline your chapter and locate the three most importent events during the American Civil War that changed the tide of battle in favor of the Untion army. Now you are reading with focus, but you might discover a dozen key events. How do you decide? You can pretty much bet that Prof. is going to ask you to talk or write about it and to defend your three choices over all of the ones you didn't pick.

If you are like me, you do not have a long-term eidetic (photographic) memory. That chapter in the American History text is forty pages (with two columns on each page; at least there are lots of pictures). How on earth are you going to memorize forty pages for the test? Well, you aren't.

taking notes (aka glossing the text or annotation)

There are tons of ways to take notes. I keep casual "to do" notes on post-its. Some folks write outlines of information-rich textbooks. Others create lists of bullet items. My daughter, now earning her PhD in forensic chemistry, learned the periodic table of elements using flash cards. Anything that works for you is good. but before you do any of that, I encourage you to take a preliminary step, glossing the text. And, yes, it is alwasy better to print it out and mark it up when possible. You could highlight a Word document on your computer, but you are not likely to go back and check your notes, so those notew won't really help. So print the text if possible and mark up the paper copy so that you can keep it in front of you for reference.

By "the text" I mean whatever you are reading (a recipe, a one-act play, an article from the New York Times online, most importantly any writing or homework or test prompt the teacher gives you. We will focus on the last of these in our next lecture, but it is an extremely important sort of text that you should be marking up. Yes, I am actually telling you you should gloss this week's Discussion 1 topic so that you don't forget and leave something out.

Ah, and that takes us to the word glossing (think "glossary," sort of). Glossing means annotating, highlight, underlining--any sort of method you might use to mark up key "things" in a text.

Ohgoodgrief, and now we have the word things to worry about. What "things"?

In general, when you read college texts (articles, textbooks, literary works, etc.), you are required to apply different analytical skills to the reading than you normally do when you read a popular novel or watch your favorite T.V. sitcom. Most popular recreational reading ends with your discovery of whodunit or whether or not the couple will marry or if the treasure has been lost forever. Reading and thinking critically demands that you read, note, consider, and often re-read the material to figure out exactly what ideas the writer is expressing.

If you are expected to discuss or write about a complex reading, which you have to do when you take an essay exam (often a mid-term or a final), or write an out-of-class essay, the teacher will probably not just want you to answer simple fact questions ("What year was the film The Exorcist made?").

Your teachers also don't really want your unsupported opinions ("Was Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chainsaw Massacre a good movie?"). That does not demonstate your ability to analyze, to figure things out.

Your teachers DO want to see how you think, not just what you can memorize. Questions will be more open-ended and will allow you to demonstrate that you understand the point of what you are reading; they will require you to support your conclusions with examples from the reading ("What does Stephen King mean when he says that horror movies help to 'Keep the hungry gators fed'?"). To answer this, you would also have to explore WHAT KING MEANS when he says we are all insane. You are not being asked to agree or disagree with his position; you have to EXPLAIN his position and even quote the evidence (examples) he gives to make his case.

Since much of the reading you do in college is fairly sophisticated (in terms of both idea and presentation), you will want to develop a method of glossing the text that works for you. Glossing the text is just a fancy way of saying, "taking notes." Underlining, circling, highlighting, numbering items that correspond to notes in a journal, marginal comments--these are all workable methods of keeping track of items in your reading. Some of the kinds of things you should note are

- passages that you think are especially significant (that contain ideas which are key to understanding the author's point/argument)

- passages you question (either they challenge your thinking or you disagree with them because they are undeveloped/unsupported in the work)

- words, phrases, references (allusions) that you are not familiar with; you really do need to look these up to fully understand what the author is saying

- anything that you think stands out, that is unusual (perhaps an ironic passage, an novel comparison, an especially effective example)

- any piece of evidence that the author uses to support a claim, a position, an argument; you will likely need to quote several of these in your writing as well as give the author credit for it

- if you are going to be required to argue a position, then you will want to find and note and credit several pieces of supporting evidence (examples) from expert sources, and you will give each of those authors credit (more on that next week

The goal here is twofold: first, you want to extract as much from your reading as possible (after all, how can you justify agreeing or disagreeing with something you don't really fully understand?); second, you want to be more aware of how other writers communicate so that you can use some of the techniques in your own writing.

let's give it a try

Stephen King's "Why we Crave Horror Movies" is an attempt to validate some horror movies as a serious art form. In his essay he lists a number of things that the superior horror movie gives to the reader; he discusses social, psychological, artistic elements in a number of films.

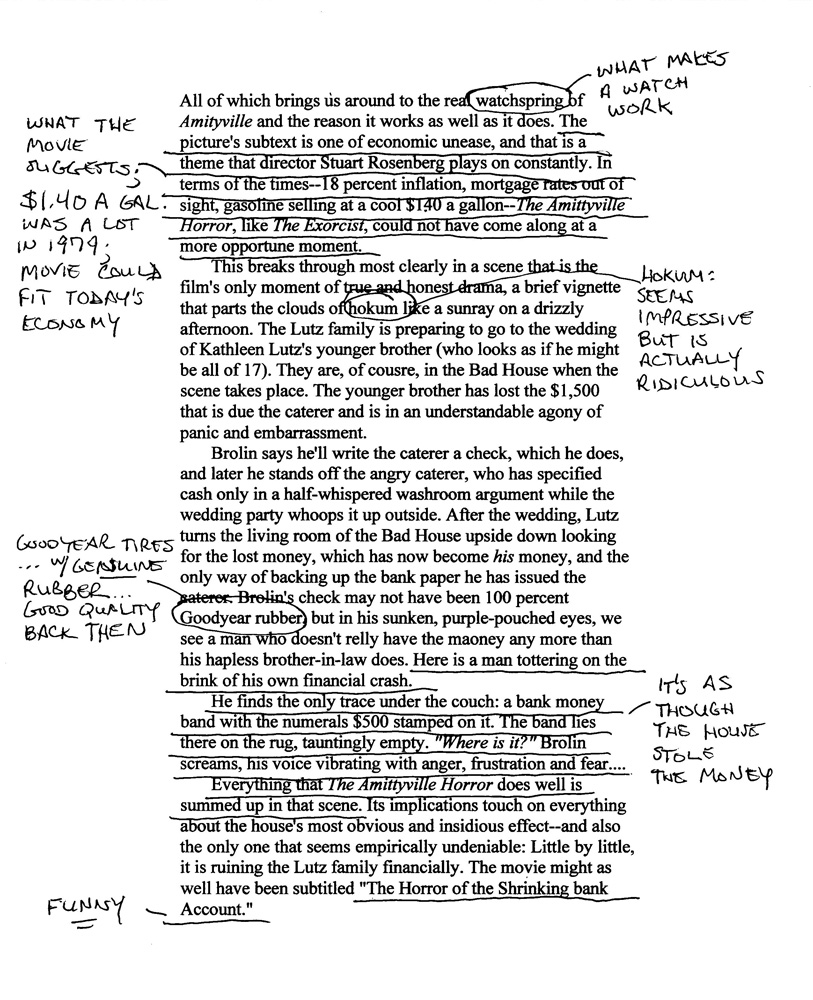

In this section of his essay he shows how the 1979 version of The Amittyville Horror, a haunted house thriller, works because it represents, symbolically, the social and economic situation of its time. In essence, the film serves as a window through which viewers can see just what was disturbing to a culture with a troubled economy in the late 1970's.

For a text version of this passage with explanations of the glossing, click here.

In this section he suggests the horror n the movie is not a result of monsters and violent death. If there is a monster, it is the house itself that is falling apart, plagued with mysterious swarms of insects, draining the bank account of the owners. As one annotation suggests, this could fit the economic downturn of the early 21st century. The housing crisis, with property values falling, people being evicted and losing life savings because the house takes up more money than they can earn--this is the horror of Amittyville. And it does not stop there; with the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020, so many people have lost work and are unable to get unemployment checks, that financial crisis is once again "the monster."

you have done your annotation...now what?

The first part of this lecture asks you to look closely at the texts you are assigned, to ask questions, look things up, draw conclusions, attempt to understand someone else's unique thinking, assess the argument being posed, and imagine how the techniques another author uses to communicate could be incorporated into your own writing. And you should be markng those texts up, taking notes.

Yes, that's a lot, and it means reading college texts can sometimes be time-consuming and challenging, especially if the ideas are new to you. And, heck, that is by folks go to college/university--to learn new ideas.

So once you have read a work and taken notes on it to try to fully understand it, you may be asked to demonstrate your understanding. This is often done in the form of a mid-term or a final exam, but it can also be oral (in a speech class, for instance) or in a more expanded sort of essay writing (in class or at home). For the online class your Discusion Questions often ask you to write very specifically about the essays you've read, to include actual examples from those readings that illustrate and support the points you are discussing. Sure, the teacher (I), want to see that you did the reading, but I also want you to be able to demonstrate analyzed (picked apart and considered the meaning of) the reading itself. This analysis requires three things: observation / quotation / explanation.

observation / quotation / explanation

integrating quotations into your essay

I am not a huge fan of formulaic writing. If students at this level submit a five-paragraph formula paper; they will likely be asked to re-do it; that formula was designed for remedial composition. Real writers don't write like that. If you doubt that just look at the readings for this (or really any) class. NONE is in the five-paragraph formula. However, for analyzing things that you read, the method works especially well for the body of the paper or discussion or exam.

Whenever you analyze what you read or hear or see, it's a good idea to use the observation / quotation / explanation formula:

OBSERVATION: Throughout your analysis you will make a number of observations or claims(your ideas about what is being expressed in the text). A lot of these will come from the notes you took, and these should be written in your own words.

QUOTATION: You then need to back up your thoughts by drawing specific supporting evidence/examples (the best examples are direct quotations which are appropriately documented with MLA standard parenthetical citations) from the author's work.

EXPLANATION: Next you must explain how the material you've quoted illustrates your topic sentence or your thesis--how does it demonstrate your observation?

Of course, your essay will have an attention-grabbing opening, will be woven together with the appropriate transition statements, will possibly end with a thought-provoking concluding example, but the biggest part of your analysis will involve observation / quotation / explanation.

let's look at an example

If you were writing an essay illustrating how Sherry Turkle's article "Why the Computer Disturbs" demonstrates "what disturbs is closely tied to what fascinates and what fascinates is deeply rooted in what disturbs" (Turkle 97), you might use the observation / quotation / explanation formula for a portion of your essay as follows:

So backing up what you say (especially when you analyze a written work) often involves your interpretations (ideas, claims, understanding) that are supported and illustrated with material from the text you are analyzing.

anticipating and clearing up a couple of questions

which I am pretty good at as Ive been teaching 45+ years now

-

But what if I disagree with the text?

It doesn't matter; this is not about you; it is about demonstrating that you can articulate your understanding of the ideas in the works you see, hear, read. Unless you are asked to write about yourself and your personal beliefs (and you will find that is pretty rare in college), get rid of "I think," "I feel," "I believe," and "In my opinion" from your college writing vocabulary. Sure, your beliefs are incredibly important. They just don't usually relate to the topics you are writing about; you are trying to show you can learn new things, after all.

I'm going to stress this: this is one of the most important writing skills you can master for college/university. In English, sociology, psychology, humanities, history, anthropology, etc. this ability to demonstrate that you understood what you read is what makes up most essays and most essay tests. So this really is important. Fortunately, it's not that complicated.

Look again at the Turkle analysis above. Look at how I open different sentences:

"Turkle opens her essay..." (this is about Turkle and her essay, and the example is from her essay)

"Likewise, Turkle explores certain ideas that are..." (again, this is about Turkle and her ideas; the quotation that follows is another example from her essay)

"What disturbs her is this idea of infinity..." (note that I am writing about "her" and her essay and her fears, not mine)

"She then turns to computers, which she finds..." (once again, this is about her observations in her essay)

-

Could I sneak in an example (not an opinion) of my own?

Sure, if it is OK with the teacher (it is generally OK with me; you can always ask first). It's easy to include examples, not opinions; here's how:

Turkle opens her essay with an example of Matthew, a precocious boy who writes his first computer program only to find he's created an infinite loop; he can't get the computer to stop printing his name, and he's frustrated that he's lost control of the machine. Likewise, Turkle explores certain ideas that are also out of a person's control. She recalls a picture book she had as a child: "I had a book on the cover of which was a picture of a little girl looking at the cover of the same book, on which, ever so small, one could still discern a picture of a girl looking at the cover, and so on. I found the cover compelling, yet somehow it frightened me. Where did the little girls end? How small could they get? When my mother took me to a photographer for a portrait, I made him take a picture of me reading the book. That made matters even worse" (Turkle 98). This example of an infinite regress reminded me of an example from my own childhood. In the Broadway men's department, the dressing room had three mirrors angled in such a way that when I looked in them I could see my front and sides, but I could also see me looking at me getting smaller, looking at me getting smaller, looking at me getting smaller, and I realized that this could go on forever. What disturbed me and Matthew and Turkle is this idea of infinity, a concept that can't be fully grasped by the limited facility of human logic. She goes on to explain that when she asked adults about the idea of infinity, about infinitely small, about endless repetition, adults did not have any answers for her "slippery questions" (Turkle 98). She then turns to computers which, she finds, are filled with these disturbing but fascinating ideas that are beyond simple explanation.

So I added my mirror example as an example to show I had a similar experience. I did not disagree with her; my essay is not about me or my opinions. It is about Turkle's essay, and I am showing I understand it. That is how you write about what you read.

and that's it!

Well, not really. There's more. We will look at more next week and the week after and so on. But that seems like a pretty solid beginning.

I wonder if anyone will print out and mark up the lecture :)

![[101 home]](btnxanim.gif)

![[class schedule]](btnhour.jpg)

![[homework]](btnhwrk.jpg)

![[discussion]](btndisc.jpg)