"and it has made all the difference" from Robert Frost's "The Road Not Taken"

GIGO (garbage in, garbage out)--this acronym made popular by computer programmers can apply to just about anything we make, from a chocolate cake to a research paper.

Determining whether evidence is credible or not is useful when we read (for example, is a print ad bullying someone into voting for a tax increase out of fear, or does it provide solid evidence demonstrating that the money will support services we need?). It is also important when we write (for example, are we expecting our reader to spend money on a treadmill just "because" we think it's a good idea, or are we presenting real examples of health benefits?).

We may think that a particular policy being considered by Congress is necessary, important, effective, or we may think it is useless, too expensive, too controlling. But if we are basing our thinking on what our parents and teachers told us to think, or if we are drawing conclusions based on biased advertisements, inflamatory speeches, unscientific and even invented statistical research, then we are not really thinking at all. We are going along with someones notin "just because"--just because we wish the world were a certain way or just because we've been trained to accept something without questioning it or just because it's easier than actually putting in the time to do the research.

Of course it's absolutely terrific that we have beliefs and opinions.

Just becuase we may believe something does not mean it is true. More important for our purposes, just because we may believe something does not mean others believe it. Whenever we speak or write write an argument, we are trying to convince someone else. That someone else has no idea how we arrived at our conclusions. To convince someone else of a conclusion, we need to show him/her how we got there, what examples, research, logic makes our conclusion reasonable.

Now here's the kicker: if we have no examples or if our examples are not reasonable, then we will fail to convince someone else that our conclusion makes sense.

so just who can you trust?

Whenever you develop an essay, you need to back up your observations with evidence. But not all evidence is of equal value. For example, if you were researching the chief causes of violent behavior among some children, you might ask a friend who has a couple of children. The response might be something like, "I just think it's what they see on television." Of course this probably does account for some imitative behavior, but many children who exhibit violent behavior are not television watchers; also, many children who watch Power Rangers and other shows larded with guns and martial arts are not particularly violent. So what is the value of the evidence you got from your friend? It's just one example from a very limited source; it does not, by itself, constitute proof.

There are two chief considerations when evaluating whether or not you have sufficient evidence to make a reasonable argument or to draw reasonable conclusions:

- what is the quality of the evidence?

- what is the quantity of evidence?

Quality of evidence refers to the credibility and reasonableness of the source (note that reasonableness is not necessarily the same as truth. Truth often involves the unseen, the unmeasurable; it is not always bound by logic, the scientific method, human reason (try demonstrating what justice or beauty or even love is concretely; just because these abstractions are not bound by a single scientific definition does not mean there is no truth to their existence). A reasonable argument involves examples that can be demonstrated, that have been observed objectively (without significant bias on the part of the observer). So in the example about children's violence above, your friend may have hit upon a truth (or not), but most thinking readers will not accept that response because

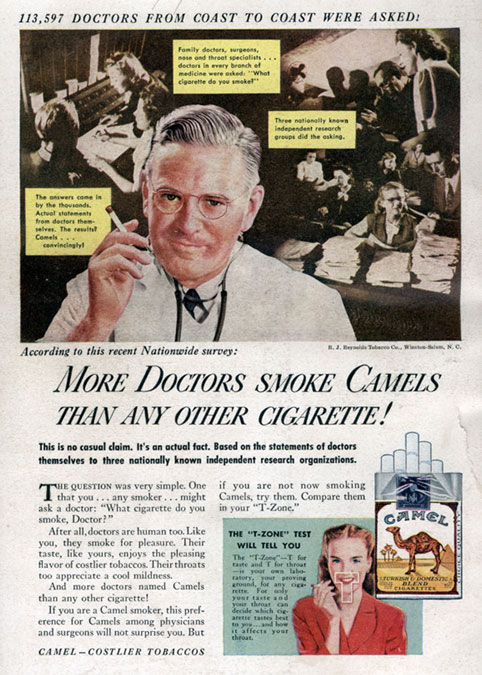

credible evidence comes from someone or some group recognized as an authority in the field being discussed (we tend to believe what doctors have to say about medical conditions; architects are generally believed when the discussion turns to earthquake retrofitting; etc.)

credible evidence is qualified (with terms such as some, often, in several cases, one possible answer); the friend who sees just one cause of children's violence is clearly over-simplifying the problem

credible evidence is supported with concrete examples (not just beliefs, moral stances, biased comments)

When we examine the quantity of evidence, we are concerned about both sizes of specific studies and agreement among large numbers of people who are recognized as authorities. One researcher discovering that ten lab rats get thinner after taking a new diet drug is not enough to convince most thinking people that there is now a new miracle cure for excess weight. Years of study of hundreds of rats (and humans) conducted by several different researchers at several different reputable institutions is much more convincing.

Whenever possible, try to apply a wide range of specific evidence to your conclusions. Look for several supporting examples from a number of credible sources. That does not mean you have to eliminate personal experience entirely. Personal examples lend human interest to your writing--use them! It does mean that personal examples are not usually enough to make a reasonable case.

now let's give it a try

Let's take a quick second look at Armin Brott's "Not All Men are Sly Foxes."

Brott is concerned that his daughter is exposed to images of fathers who are uncaring and absent. This disturbs him because he is noting like that, and he fears the repetition of this stereotype will give his daughter a false impression of men/husbands/fathers. Now he could approach this concern in a couple of ways:

He could rant after reading a childrens book, "All of these books demonize dads; it ticks me off!"

He could actually research just how common this stereotype is.

The first approach is much easier; it requires no thought, and it gives him an opportunity to vent. The second approach, though, is the more sensible, logical, and the results of actually looking into the subject will allow him to reach a reasonalbe conclusion.

So what does he do? He actually goes to the library, checks out many of the most popular books for young children, and reads them. Since he is concerned about what is currently popular, he will not dip back into books written long ago; they are not relevant for researching current trends. The results are the results; he does not make them up.

He does find the negative steroetype, but it is only in some of the books. Like any responsible researcher, he looks at just how frequent this occurs. A large proportion does show mother/child interaction exclusively, but many of the books show mother and father or even just father playing with the kids; he does find the negative father stereotype in a significant number of books, enough to be disturbing to him, but he qualifies his findings; it is not "always" (over-generalization / fallacy). He also examines variations. Sometimes dad is absent because the child is raised by a single mom; sometimes the father is just away at work all day and is too tired to play when he gets home.

He could easily continue his research looking at television shows, movies, news items, and so on. In any case, he would have to actually look at the examples, honestly note just how often this occurs, qualify his findings, present a reasonable conclusion. He might come up with something like this:

Although there are many examples on popular children's television shows of loving fathers who care for their children, a large number of these shows present dads as being uncaring or absent, and this could give children a false impression of men, husbands, and fathers.

Now that sounds like a thesis sentence for a paper topic (check out the topic choices for Paper 2). The paper would be made up of loads of concrete examples described in detail. It would show trends (not never or always thinking) and would cite the sources looked at (researched). It would certainly have a Works Cited page (in MLA format for our purposes) as well :)

there's more here than meets the eye

While some of the writing you do in college/university focuses on description or narrative or process analysis or simple comparison/contrast, most of your writing will be essay analysis (for example, will be supporting or contradicting a claim made by Armin Brott, Emily Prager or by Armin Brott) and research, which requires you to locate and integrate outside material to back up your thesis (conclusion).

There is an important concept there, so let me recap: you will base your conclusion on research, not on your personal opinions, not on your beliefs, not what you want to be true.

Let's apply that to the Prager essay. She claims Barbie is responsible for the low self-esteem of millions of women. You may agree that Barbie dolls are the source of huge numbers of eating disorders, but on what are you basing that? It's possible this is personally true of you (or not), but you, alone, do not prove that this doll is causing a significant trend. There are more than 1/3 of a billion people in the U.S.; you are (and I will round this out; the number changes moment by moment) 1/333,000,000th of just the U.S. alone. Statistically, alas, that is not very significant.

So to see if Prager's ideas make sense, you could do first-hand research and ask women who played with Barbie dolls. You certainly can't ask the millions of women who played with the doll. You could also stand in a crowded mall and see if, indeed, most women do look exactly like Barbie, if couples look like Barbie and Ken, and so on. First-hand research is terrific, but your time and resources are limited, so your paper will not be thoroughly conclusive. You could also search the school's library database and see if you can find examples of women (such as Angelyne or Valeria Lukyanova) who have styled themselves after Barbie. Are there billions of them? Millions? Just a handful? The goal is to test Prager's ideas against some actual, reasonable evidence. Whatever results you get--THAT is the side you will take because you are a reasonable person, no?

Unlike Prager's essay, Brott's essay makes qualified (that is he does not over-generalize or claim 100%) claims, and they are based on actual evidence (he went to the trouble to read several children's books to see what they actually contained, and he found lots of different portrayals of families/fathers, but he noticed there were some trends/patterns).

The trend to portray fathers as absent, uncaring, etc. may still be true, and it may no longer apply (most likely there is a little bit of both, but you should be able to notice trends here in the 21st century. Since your goal is to see if his ideas are currently relevant, you will need to look at current examples (from the past five years or less.

Since he looked at a popular medium (books for young children), you will do the same, but you can choose from television shows for younger children (from pre-school to early elementary school), movies for younger children, books for younger children. You can approach this in a slightly different with using advertising campaigns. There are several ad campaigns showing fathers interacting with their children--these do not show that the media is influencing children (as a children's book might), but they might show how the larger media views father/child relationships.

You will look for patterns that agree/disagree with Brott's findings, and you will base your conclusions on whatever patterns or trends you find those books or shows or ads. Whatever results you get--THAT is the side you will take because you are a reasonable person, no?

but wait! how does Gary Cross manage to draw his conclusions?

That's another element of critical thinking, to demonstrate that you can look at something (in this case from popular culture) and look beneath the surface, at implications and suggestions and symbols that are logical. There is actually an entire field of study that relates to this activity; it is called semiotics. If you want some relatively quick information on this field, you might want to visit Daniel Chandler's "Semiotics for Beginners" website. Even his introduction to the subject is pretty weighty stuff, but at its heart is this idea:

If you look closely at elements of popular culture (art, music, television, movies, architecture, writing, fashion, advertising, even toys and games.) from any given time and place, you will likely see patterns. The patterns suggest a dominant idea or value or attitude or social custom or tradition from that time and place. In other words, patterns in popular culture are a reflection of that culture.

For example, from the abundance of militant toys marketed to boys in my childhood (plastic army men, all sorts of toy weapons, model fighter planes and submarines, and so on), you would get a sense that coming out of WWII, the U.S. was essentially a hawkish (pro-war) nation. It makes sense. We had just come off a huge military win. At the same time, my sister had her Betsy Wetsy doll (complete with stroller) and one of the first Easy-Bake ovens. Here a second pattern emerges: boy toys were distinctly different from girl toys, and this suggests that in the 1950's there were distinctly different traditional roles for males and females--boys were to grow up into rugged, strong protectors; girls were to grow up to become homemakers.

A quick look at the roles that the majority of males and females held in the 1950's shows that this "message" fairly accurately represents 1950's suburban U.S. reality. As late as the early 1970's there were very few women (allowed) in the science programs at schools such as UCLA. My father worked a 9-5 job, and my mother took care of domestic chores, and this was the norm for the majority of men and women in middle-class America at the time.

Cross looked at Barbie, the range of jobs she has had, her own (pink) muscle car and her own dream home and saw the emergence of new opportunities for young women. As Barbie became more independent and had more options, young women in the U.S. were becoming more independent and had more options. Whether the doll helped spearhead some of these changes or was a reflection of the changes is open for debate, but Cross saw logical parallels.

when is a Barbie doll not just a Barbie doll?

Of course a Barbie doll is a Barbie doll, but we have read two essays that find much more depth in this still-popular toy. They both see the doll as representing or symbolizing or suggesting certain values common back in the 1960's. So Barbie is a doll, but she may also be a sign that a semiotician could try to decode.

The Gary Cross article made a powerful suggestion:

The Barbie doll sends a message that girls could become the independent women who fueled mid-century America's free-market economy.

Where on earth did that idea come from? How are we supposed to leap magically to these sorts of heavy conclusions? Did the creators of Barbie sit down to create some sort of symbol? Isn't this some English-teacher-made-up thing?

It's certainly not likely that Ruth Handler sat down and thought, "I think I will create a symbol of free-market economics." It is likely she did sit down with others and think about a product that would attract sales, and she succeeded amazingly. The success suggests that the doll appealed to something that was attractive to those buyers. If she had created Barbie as a communist doll in the 1960's, she would not have sold millions of units. Why not? Because America was in the midst of the Cold War, and communists were widely feared. She had to fit an image acceptable to huge numbers of consumers. The statement above may be one of those "things" that consumers found acceptable because it fit a way of thinking at the time.

And, as with so many other things in this class, arriving at these heavy conclusions is not really magic at all. It does take some work, though. Here is how it's done:

First we must make actual observations. We need to push aside all assumptions we have about Barbie, and we have to actually look.

With some fairly easy reseaarch, we could look at Barbie (and Barbie advertisements) from the 1950's-1960's and see that nearly all of her accessories were fashion-related. She had (purchased separately) cocktail dresses, slacks, heels, purses, hats, even a wedding dress.

By the 1970's-1980's the doll, the accessories, and the advertisements showed that she could be dressed as a surgeon, a business woman, a McDonald's employee, a student, a mother, and so on. This later Barbie had her own Corvette, her own lushly-furnished beach home.

We now have two things we can observe, and we can (if we look at old advertisements or maybe a history of the doll) provide several examples to demonstrate each. We do not make any of this up. Everything, so far, is directly observable, and we can record what we discover example by example. Based on all of the examples we jot down, we look for patterns in what we've observed:

When Barbie was first created, all of her accessories were fashion-related, but in the decades that followed, her accessories expanded to include a car, a house, and clothing that showed her being everything from a student to a mother to a career woman.

So far, there's no magic involved. All of that is directly observable. Still, it is not a conclusion. What does that suggest? What idea might we be able to draw from these changes? This requires us to think about what those patterns add up to. How about this:

Barbie has changed over time to reflect some of the changes in options available to young women. The original doll was just a stylish dress-up doll, which suggests that women in the 1950's and early 1960's were thought of as objects to dress up, to look feminine. By the 1970's Barbie had her own transportation and home--both signs of independence and success--and she was shown doing all kinds of work, which suggests that women after the 1960's were seen as competetive in the workplace.

Even if we had no way of looking at the actual history of the emergence of women's rights in the United States during these decades, the changes in the doll (which still sold millions of units, meaning it was still acceptable to millions) suggest that women were viewed differently and had more options available to them following the 1960's. By a stroke of great fortune, we actually can study this history. It is very recent. It turns out the conclusions we drew fit what happened historically.

so the process is not magic, but you still not be sure why we would do this; what's the point?

The main points very simple:

we need to base conclusions on observations, on actual examples, or credible evidence, not just whims and notions and unsupported opinions; otherwise, the choices we make (who to vote for, who to marry...or not, what to buy, what career field to enter, what religion to follow, etc.) make no sense.

the material we cover in college/university often requires us to think; after all, education is about expanding your world view as much as it is about expanding your skills.

the popular culture we are surrounded with reveals a great deal about what is important to us; if we pay attention and look closely (deeply), we can find very significant ideas in places we don't expect to find meaning; therefore, we need to read closely and carefully

But wait, there's more:

our view of the world is not the same as everyone else's

even large social groups change their traditions and values over time

a lot of what we think is true is based on almost nothing (or, as much as you may wish to deny it, much of what we think is true is based on unchallenged stereotyping)

![[101 home]](btnxanim.gif)

![[class schedule]](btnhour.jpg)

![[writing assignments]](btnhwrk.jpg)

![[discussions]](btndisc.jpg)