hmmm...it looks like the entire semester will be here in the second lecture

So you find yourself in a class called College Reading and Composition I

Who needs this? You know how to read, and you know how to write. You have been doing it for years now. Sure, you may not know every word in the dictionary, and you may not be the world's best writer (whatever that means), but neither do I (and neither am I), and I do this for a living.

Let's be honest, though, you probably do know how to read.

let's give it a try

Read the following page from Stephen King's "Why We Crave Horror Movies" from his book Danse Macabre (it is short):

All of which brings us around to the real watchspring of Amityville and the reason it works as well as it does. The picture's subtext is one of economic unease, and that is a theme that director Stuart Rosenberg plays on constantly. In terms of the times--18 percent inflation, mortgage rates out of sight, gasoline selling at a cool $1.40 a gallon--The Amittyville Horror, like The Exorcist, could not have come along at a more opportune moment.

This breaks through most clearly in a scene that is the film's only moment of true and honest drama, a brief vignette that parts the clouds of hokum like a sunray on a drizzly afternoon. The Lutz family is preparing to go to the wedding of Kathleen Lutz's younger brother (who looks as if he might be all of 17). They are, of course, in the Bad House when the scene takes place. The younger brother has lost the $1,500 that is due the caterer and is in an understandable agony of panic and embarrassment.

Brolin says he'll write the caterer a check, which he does, and later he stands off the angry caterer, who has specified cash only in a half-whispered washroom argument while the wedding party whoops it up outside. After the wedding, Lutz turns the living room of the Bad House upside down looking for the lost money, which has now become his money, and the only way of backing up the bank paper he has issued the caterer. Brolin's check may not have been 100 percent Goodyear rubber, but in his sunken, purple-pouched eyes, we see a man who doesn't really have the money any more than his hapless brother-in-law does. Here is a man tottering on the brink of his own financial crash.

He finds the only trace under the couch: a bank money band with the numerals $500 stamped on it. The band lies there on the rug, tauntingly empty. "Where is it?" Brolin screams, his voice vibrating with anger, frustration and fear....

Everything that The Amittyville Horror does well is summed up in that scene. Its implications touch on everything about the house's most obvious and insidious effect--and also the only one that seems empirically undeniable: Little by little, it is ruining the Lutz family financially. The movie might as well have been subtitled "The Horror of the Shrinking bank Account."

ok, that was easy enough

Was it? What was it about? What is The Amittyville Horror? Who is "Brolin"? King writes, "In terms of the times"; what times is he talking about? Is 18 percent inflation high or low (compared to what)? What does "watchspring" mean? "vignette"? "empirically"? More important what does this passage mean? What is King's main point here? What is he trying to prove to me? How has he built a convincing argument? Is it a convincing argument? Is it an argument at all?

If your answer to any of those is "I'm not sure," then you didn't really READ the way you need to read in college/university.

oh...

In general, when you read college texts (articles, textbooks, literary works, etc.), you are required to apply different analytical skills to the reading than you normally do when you read a popular novel or watch your favorite T.V. sitcom. Most popular recreational reading ends with your discovery of whodunit or whether or not the couple will marry or if the treasure has been lost forever. Reading and thinking critically demands that you read, note, consider, and often re-read the material to figure out exactly what ideas the writer is expressing.

If you are expected to discuss or write about a complex reading, which you have to do when you take an essay exam (often a mid-term or a final), or write an out-of-class essay, the teacher DOES NOT just want you to answer simple fact questions ("What year was the film The Exorcist made?").

Your teachers also DO NOT really want your unsupported opinions ("Was Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chainsaw Massacre a good movie?"). That does not demonstrate your ability to analyze, to think, to figure things out.

Your teachers DO want to see how you think, not just what you can memorize. Questions will be more open-ended and will allow you to demonstrate that you understand the point of what you are reading; they will require you to support your conclusions with examples from the reading ("What does Stephen King mean when he says that horror movies help to 'Keep the hungry gators fed'?"). To answer this, you would also have to explore WHAT KING MEANS when he says we are all insane. You do not have to agree or disagree with his position; you have to EXPLAIN his position.

Since much of the reading you do in college is fairly sophisticated (in terms of both idea and presentation), you will want to develop a method of glossing the text that works for you. Glossing the text is just a fancy way of saying, "taking notes." Underlining, circling, highlighting, numbering items that correspond to notes in a journal, marginal comments--these are all workable methods of keeping track of items in your reading. Some of the kinds of things you should note are

- passages that you think are especially significant (that contain ideas which are key to understanding the author's point/argument)

- passages you question (either they challenge your thinking or you disagree with them because they are undeveloped/unsupported in the work)

- words, phrases, references (allusions) that you are not familiar with; you really do need to look these up to fully understand what the author is saying (NOTE: this also includes doing contextual research; when was the movie above made, what could $500 buy then, and so on?). Yes, this means you need to look things up.

- anything that you think stands out, that is unusual (perhaps an ironic passage, an novel comparison, an especially effective example)

The goal here is twofold: first, you want to extract as much from your reading as possible (after all, how can you justify agreeing or disagreeing with something you don't really fully understand?); second, you want to be more aware of how other writers communicate so that you can use some of the techniques in your own writing.

ok, what does that look like?

For a text version of this passage with explanations of the glossing, click here.

you have done your annotation...now what?

You figure out the implications of what you have just read. What is the point? What "things" in the reading suggest that?

In this section he suggests the horror in the movie is not a result of monsters and violent death. If there is a monster, it is the house itself that is falling apart, plagued with mysterious swarms of insects, draining the bank account of the owners. As one annotation suggests, this could fit the economic downturn of the 21st century. The housing crisis, with property values falling, people being evicted and losing life savings because the house takes up more money than they can earn--this is the horror of Amittyville.

Stephen King's "Why we Crave Horror Movies" is an attempt to validate some horror movies as a serious art form. In his essay he lists a number of things that the superior horror movie gives to the reader; he discusses social, psychological, artistic elements in a number of films.

In this section of his essay he shows how the 1979 version of The Amittyville Horror, a haunted house thriller, works because it represents, symbolically, the social and economic situation of it's time. In essence, the film serves as a window through which viewers can see just what was disturbing to a culture with a troubled economy in the late 1970's.

Very cool, but why would I care about an old move or Stephen King's ideas or ???

Check the sidebar(the pinkish box on the right).

the writing part

In a history class, a psychology class, a sociology class, a humanities class, certainly an English class, and on and on, you will often be asked to write, to respond to some topic(s) in paragraphs, in an in-class essay, in longer at-home essays.

Of course I know many students do not like to write (or read), but here you are in college/university, and the only way your professors can measure your ability to understand and articulate the material (not just the facts but the significance of the details, the ideas) is through your communication(s)...generally that means your writing. Again, your opinions ("I don't really like horror movies" are not what they are looking for; your ability to understand and explain (with detailed evidence/examples) what you have studied is what counts.

important notice, the universe is not always divisible by three

I am not a huge fan of formulaic writing. If students at this level trot out the five-paragraph formula that was designed for remedial composition, then their grades will not be good.

That bears repeating: if you turn in five-paragraph formula papers, your grades will not be good.

Look at the more organic ways real writers write (get some ideas from the readings in our class). The writing is detailed, yes, and the examples serve to support and idea, but most notably is the fluid nature of these papers/articles--one idea flows into the next into the next. They can cover three paragraph or thirty. You want to mirror some of those techniques in your own papers. However, for analyzing things that you read, there is a method works especially well--observation / quotation / explanation.

Research papers (more on that in future lectures) always require you to incorporate material from outside sources which you document both in the paper and on a Works Cited page at the end of the paper. But using source material which you document is not just for research papers.

Whenever you analyze what you read or hear or see, it's a good idea to use the observation / quotation / explanation formula:

OBSERVATION: Throughout your analysis you will make a number of observations (your ideas about what is being expressed by the other author). A lot of these will come from the notes you took, and these should be written in your own words.

QUOTATION: You then need to back up your thoughts by drawing specific supporting evidence/examples (the best examples are direct quotations which are appropriately documented with MLA standard parenthetical citations) from the author's work. Note: the material assigned in your handbook explains exactly how to properly use parenthetical citations.

EXPLANATION: Next you must explain how the material you've quoted illustrates your topic sentence or your thesis--how does it demonstrate your observation?

Of course, your essay will be woven together with the appropriate transition statements, but the greater part of your analysis will involve observation/quotation/explanation.

If you were writing an essay illustrating how the article "Why the Computer Disturbs" (which we will be reading later in the semester - it is in the Week 7 Readings folder if you'd like to check it out now) demonstrates "what disturbs is closely tied to what fascinates and what fascinates is deeply rooted in what disturbs" (Turkle 97), where the (97) is the page number from Turkle's work where the quotation was found; you might use the observation / quotation / explanation formula for a portion of your essay as follows:

This is something you should be incorporating regularly into your class discussions (remembering to also include actual examples and related ideas). When you do your research paper, you will use several texts (some written, some not) to back up your various claims. Be sure that you always introduce and explain this source material, and always remember to give credit to these other sources with parenthetical citations.

anticipating and clearing up a couple of questions

Writing is not a formula, well, sort of. If you studied both the short (partial) Turkle article analysis and then the short (partial) Rose article analysis, you may have noticed that the body of an essay analysis really is formulaic. Yes, I broke it down into the observation/quotation/explanation formula, but let's clarify that just a bit.

It is always a great idea (unless the teacher/assignment tells you otherwise, and it's a great idea to ask the teacher first) to put some real-world examples in an analysis that reinforces what the article/essay/text is saying. However, the heart of the analysis is not about YOU; it is looking at and clarifying what the AUTHOR is writing/saying; it is breaking the text down into key ideas, showing how the AUTHOR develops those ideas, demonstrating that you really understood what you read.

I'm going to stress this: this is one of the most important writing skills you can master for college/university. In English, sociology, psychology, humanities, history, anthropology, etc. the format may shift between MLA and APA (not a big deal), but this ability to demonstrate that you understood what you read is what makes up most essays and most essay tests. So this really is important. Fortunately, it's not that complicated. For most newer college writers, the hardest part is getting rid of "I think" and "I feel" and "I believe" and "In my opinion"--those do not belong in this class at all.

Look again at the Turkle analysis above. Look at how I began different sentences:

"Turkle opens here essay..." (this is about Turkle and her essay, and the example in that sentence is from her essay)

"Likewise, Turkle explores certain ideas that are..." (again, this is about Turkle and her ideas; the quotation that follows is another example from her essay)

"What disturbs her is this idea of infinity..." (note that I am writing about "her" and her essay and her ideas, not mine)

"She then turns to computers, which she finds..." (once again, this is about her observations in her essay)

Notice that I did not agree or disagree with her; my essay is not about me or my opinions. It is about Turkle's essay, and I am showing I understand it. That is a analysis, and in this class we are learning to write analysis.

ok, that's great for the discussions, but what about the longer papers? any tips?

Of course, and more will come in upcoming lectures. For now, here's a starting thought:

Last week's Annie Lamott exercise, and this week's discussion gets you as far as using your senses and recording what you experience into lists of words. It is definitely writing, but it's not exactly university-level essay writing or even creative story/novel writing.

Writing is a process, and it may not be the process you were shown in K-12 (maybe it is, but I've had a great many students, and I've seen a lot of weirdness). One of my students, David M. asked me about the process (my weirdness, sort of like learning to play songs with 8 notes) I was introducing in my 101 class; it was not what he had learned in high school, and he was in the AP classes. And here was my reply, which I posted in a Canvas Announcement called, "OK, WHY ARE WE DOING THIS?"

I will start with a guess, something I cannot actually know for sure, but I'm pretty sure. Most of you think writing a paper is sitting down at the computer, starting, typing away, getting to the end, and turning it in. And, in fact, if you are quite "good" (?) at writing, you likely can get away with that in a whole lot of writing situations. I know that I could and still can if I'm writing something in the 4-8 page range. I'm pretty sure most of you could do the same with a 2-page paper, BUT, AND THIS IS IMPORTANT, PAPERS IN THIS CLASS, AT THIS LEVEL, ARE FOUR FULL PAGES, NOT TWO.

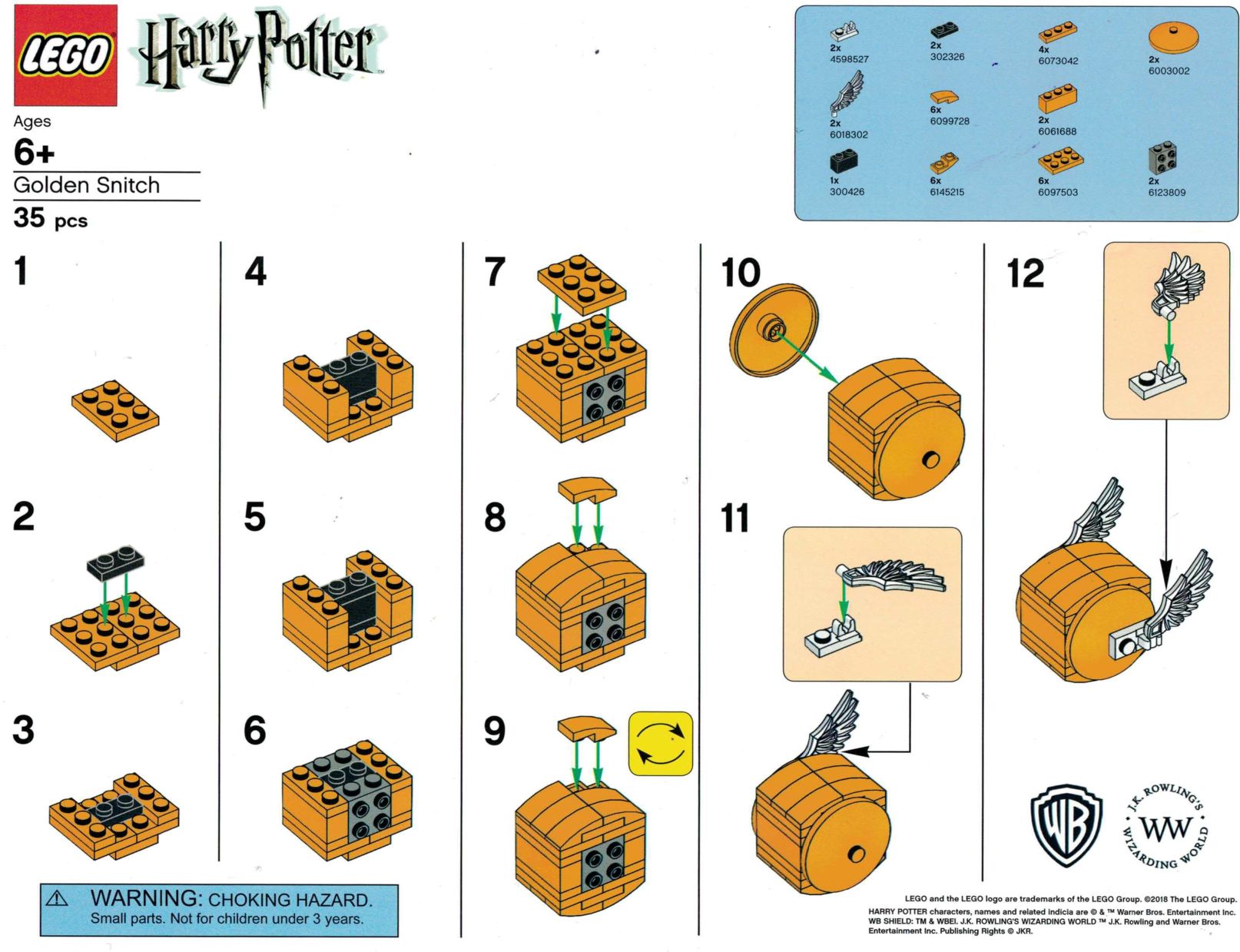

And then I hit my first (of several) 20-page term paper. Term as in TERMINAL because this thing and my Final added up to my entire class grade. It is very hard for any writer to just reel off a great 20-page paper, but that is not how writers write. Writers BUILD papers. I start with hastily-scribbled notes on bits of paper around my computer hutch. An idea for the middle joins an idea for the end joins another idea for the middle, and so on. It is like dumping a bunch of Legos on the table (yes, that is a nod to Alexa B's discussion). But what will those Legos turn into, a bunny or a castle or a fire truck? I need a plan that I can follow and build this on top of this on top of this until the finished "thing" emerges. I could possibly eyeball it, but if it is complex, it will look bad. And so I do this:

Yes, that is the Golden Snitch from the Harry Potter books from Anthony Z's discussion

You have hundreds of colorful Legos (or maybe descriptions of things in a room). You sort through them to get the best ones, the ones that you need, and THEN you start building. Along the way, if something is not working, well, revise that bit, but it is like building a tiny house that you design. You need plans, you need materials, you start with a foundation and THEN work on the frame and THEN rough in plumbing and electrical and THEN put up the exterior and interior walls, and so on.

You do not wave a magic want and, *POOF* a house appears. Maybe Harry Potter could, but...

In writing this is called "scaffolding," and that is the mysterious process I am having you learn. Do you need it for a four-page paper? Maybe, maybe not. It is something you are likely to need at some point in your college/university career (and maybe in life afterwards). And I invite you all to tell me (if I'm still around) four or five years from now).

Anyway, a lot of what we do in the Class Discussions (they are not just chat) will generate some material for your essays papers. If you were in a class that required you to write a 20-page research paper (someday you might be), those shorter papers can often be expanded on for longer papers. In the old days we broke all of this down into steps:

pre-writing (such as brainstorming or note taking or free writing), which is getting thoughts quickly on paper, though not at all polished/finished

outlining or planning out the larger sections of the paper and figuring where the notes from step 1 fit in and where you will need to find more material to fill out each section

drafting (making a rough draft of the paper using the original notes plus the other material you looked up and will quote/cite in your paper)

working on the polished draft (proofreading, editing, making sure all documentation and formatting are correct, polishing each section)

Writing (mostly) IS a process, like playing guitar and sweating over those dratted scales drills for eternity until your fingers bleed. By the time your fingers are calloused, you are building on those drills, and you have added A, D, and E chords to your repertoire, and you can fake 1/2 the British Invasion songs from the 1960s. Figure out how to barre them, and then you can fake it on stage. NOBODY (not even Hendrix) starts out as Hendrix.

![[101 home]](btnxanim.gif)

![[class schedule]](btnhour.jpg)

![[homework]](btnhwrk.jpg)

![[discussion]](btndisc.jpg)