what did we learn last week?

Quite possibly we learned lots of things, but the two ideas that I hope stood out most are:

- the stories (poems, plays, novels) that get shoved in these literature anthologies are not always simple; they contain ambiguity; they require reading, re-reading, note-taking, thinking.

- to try to make sense (get to the meaning or theme) of these stories, you need to read really, really closely, just as I went through "All About Suicide" almost sentence by sentence.

If you casually breeze through the stories, of course you are likely to throw up your hands and say, "I don't get it." If we go back to that car analogy from Lecture 1, it would be like going out to your car, turning the key, hearing the ker-THUMP, throwing up your hands, and saying, "Something's going on, but i don't know what it is" and then just driving away ignoring the (ominous) noise.

Analysis takes some time, but the good news is that there are certain elements you can look for to make the process easier. Your textbook breaks down several literary elements that may be significant in the story you are reading. For example, "How to Talk to Your Mother (Notes)" would not work if Ginny were born in 1995; time and place are important in that story, but sometimes setting is just setting and not particularly significant. Do go over the elements, and use your text to help you, but here is a method that works pretty well and works quite often, and it's simpler:

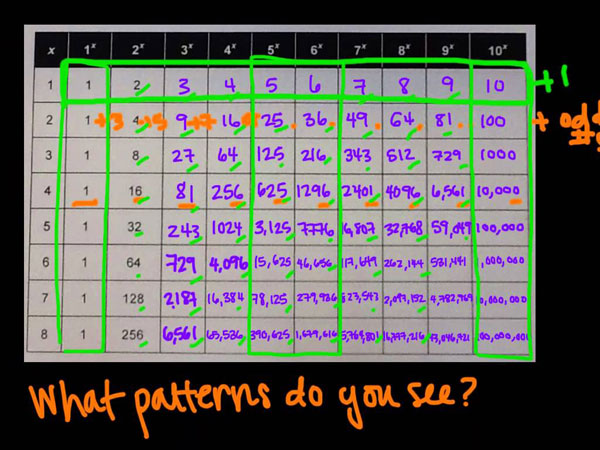

look for patterns and peculiarities

But let's come back to this in a bit; let's go backwards (this lecture is going to go backwards for a bit)

the first (quick) reading

Your text explores how to read through, take initial notes while reading actively, and so on. If the goal is to discuss or write about the story, then you will need to figure out what it means (and, remember, it can mean more than one thing). That conclusion can usually be framed in a thesis statement:

The repetitious plot structure of Luisa Valenzuela's 'All About Suicide' suggests that no matter how many times someone tries to make sense of suicide, it cannot really be fully known."

But wait, that was not immediately apparent on the first quick reading. That took a whole lot of analysis to arrive at. True. The thesis is rarely created after the first quick reading. It comes later. Before that, you need to ask questions about what you read. If we can eventually answer those questions, the answers will become the thesis statement(s) that will launch your discussion or essay. We are going to try this out with John Updike's "A&P" (be sure you have read the story, or this will not make much sense).

So I read the story, "Blah, blah, blah." Stuff happens to people I don't know. Sammy is the narrator, and at the climax (the point where the story makes its ultimate turn; typically, the main character makes a choice or fails to) of the story he quits his job at the supermarket because he feels his boss is embarrassing these three girls in bathing suits. After that he goes out to the parking lot hoping to see the girls, but they are gone (those things that happen after the climax are called the resolution).

Not much happens. All things considered, I would rather watch an episode of Twin Peaks or Sense8. Still, the story is in the textbook, and it was assigned, so I better look for something here. I have a few immediate questions:

- Is Sammy just a dumb kid who quits his job, or is he acting out the classical role of heroic knight in shining armor coming to rescue damsels in distress?

- Is Sammy really all that upset that he now has no job?

- Why the heck are those girls in the store "in nothing but bathing suits" (142), and why is everyone making such a big deal out of it?

Note: for that third question I actually wrote down a note, a quotation from the story; I am ahead of the game. WOOT!

I could probably come up with more quick questions, but this is plenty to start with. Now it's time to try to answer the questions. For this lecture, I will mainly look at question 1: "Is Sammy a hero or not?" It's time to go back to

look for patterns and peculiarities

Especially in shorter fiction (short stories, poems, one-act plays), if an author takes time to repeat something (a kind of image, a word or phrase, etc.), it is meant to stand out. Likewise, anything that is odd, weird, peculiar will pop out, and it is very rare that that is accidental. The author is saying, "LOOK AT THIS!"

If we are looking for evidence to answer our question, "Is Sammy a hero?" we need to think about what makes a hero. Here are some things that come to my mind:

- a hero is self-sacrificing

- a hero does not expect to be rewarded

- a hero has a "good" character

That's enough to get started with. Now the long part. I need to go back through the story, taking notes (this is very important; you will need these notes later) looking for things that are described/narrated that tell me if Sammy is self-sacrificing, expects no reward, has a heroic character. This story has a lot of material that addresses these points, and here are my notes just for one page of the story (I like to photocopy the story and then write on the photocopy, but feel free to mark up your textbook; you paid for it):

That is a lot to work with already, and there are examples like this throughout the story. Don't worry if you can't decipher my sloppy writing and abbreviations; I will explain examples in a bit. If your notes are sloppy, that's fine. Just be sure they make sense to you, and be sure you have enough notes--more is (usually) better.

Just on that first page, there are several patterns that help answer some of our questions; it is time to fill in lists that relate to the qualities I am looking for and tie them to annotations (highlights, underlining, marginal notes) I made on the story:

a hero has a "good" character

Sammy is a sexist; he complains about McMahon checking out the girls, but he's looking at their flesh: "She was a chunky kid, with a good tan and a sweet broad soft-looking can with those two crescents of white just under it where the sun never seems to hit, at the top of the back of her legs" (142).

He is even more sexist when he says, "You never know for sure how girls' minds work (do you really think it's a mind in there or just a little buzz like a gee in a glass jar?" (142)--he is saying girls have no brains!

He is in a service job, but his service is lousy, and he is disrespectful to customers; he calls one woman a witch: "She's one of these cash-register watchers, a witch about fifty with rouge on her cheekbones adn no eyebrows" (142). Later he is going to call customers "sheep" (143, 146), "house slaves with varicose veins" (143) and "pigs in a chute" (146). He doesn't seem to have a very good character.

a hero is self-sacrificing

I am not going to go through all of the examples; you can do that on your own. Here is a quick run-down, though: Sammy does not really like his job, and he did not seek it out in the first place (his parents got him the job), and it is not as if he will never work again. Find quoted examples of each of these statement.

a hero does not expect to be rewarded

Again, you can fill in this section, but there are several examples showing he is disappointed he is not going to get a date or a kiss or at least recognition: "The girls, and who'd blame them, are in a hurry to get out, so I say "I quit" to Lengel quick enough for them to hear, hoping they'll stop and watch me, their unsuspected hero" (145).

So far, I am building a pretty strong case for "Sammy is NOT a hero," and the list will grow as I find more examples from the story. Is there anything in the story that supports the other position--"Sammy is a hero"?

Even though he doesn't really like it, Sammy does give up his job, and his parents will probably yell at him, and he won't have gas money to take Peggy Sue to the drive-in until he gets another job.

And then there is the peculiar (remember, we are also looking for things that are peculiar) last line of the story: "and my stomach kind of fell as I felt how hard the world was going to be to me hereafter" (146). This doesn't even make much sense; it's melodramaatic, and Sammy is young, but quitting this job will not destroy his life. I could ignore this or try to make sense out of it. It's best not to ignore it.

First, the story is a flashback to an earlier time. We know this because Sammy says, "Now here's the sad part of the story, at least my family says it's sad but I do't think it's sad myself" (144). Sammy can't know his family's reaction unless the story is being told after the events he describes. Those events end before he goes home. That means he has had some time (how much?) to discover "how hard the world was going to be." To find out why it was hard, we should go back to that key moment when Sammy quits. Lengel knows Sammy is being rash, tells Sammy he will feel this for the rest of his life and that he does not really want to do this. Sammy thinks, "It's true. I don't. But it seems to me that once you begin a gesture it's fatal not to go through with it" (146).

So what has just happened? Sammy shows he has integrity. He makes a gesture, and he does not weasel out of it. This is the event he is looking back to where he knows he will live life as a person who keeps his word, and that is harder than not following through.

so is Sammy a hero?

My short answer is, "Yes." He is a rare person who will live his life with integrity. I've taken enough notes above to make the case for that.

so my thesis should be...?

The word tricky will come back in play this week.

After taking all of my notes, on all of my questions, I have to settle on a topic and devise a thesis. The thesis is my subject plus the point/claim I will attempt to prove about my topic. The subject is the author and story title, and the point/claim is the conclusion I arrived at about Sammy's being a hero or not. It will look something like one of these:

In John Updike's "A&P," the main character, Sammy, is a hero.

In John Updike's "A&P," the main character, Sammy, is not a hero.

Why did I write both positions when I told you already I think the story is about a hero?

There is not necessarily one right answer. I will look over my lists. The list showing he is sexist, disrespectful, bored, disinterested in his job, wishing for recognition will be a very long list with lots of examples. I can easily get a paragraph on each of those points. This lists suggesting he is a hero is really short. Can I get a four-page paper out of that? It is possible, but it will be hard. My inclination is to make life easy for myself (I guess I am not like Sammy), so I will probably select the following:

Although Sammy, in John Updike's "A&P," does give up his job when he feels Lengel is embarrassing three customers, his actions are not really heroic.

I've added the opposing position with my "Although" statement, and I've clarified my position with a little more detail. Note that the author and title are both in the thesis. It is clear what point I am going to develop and illustrate in my paper, and that point will be the focus of the whole paper; I will not take both sides. Could you take the harder side? Of course!

on to the essay (this lecture is nearly done...*whew*)

Now you take the material from your notes, sort it into meaningful categories (Sammy is a sexist; Sammy is disrespectful, etc.) and build your paper using the OBSERVATION-QUOTATION-EXPLANATION formula. After your paper's opening (which should be lively, if possible, and should relate to the thesis somehow), you will put in your thesis. Then you will suppport that thesis with various claims (obervation) which you back up with quoted/documented examples from the text (quotation) and then transitoinal sentences that explain how those examples fit and then lead on to your next point (explanation).

I call it a formula, but it's really more of a general guideline. It allows you to get enough of your own thinking into the discussion/essay, and it shows that you can support your conclusions with evidence (and know how to document that evidence).

If you would like to see what the beginning of an essay on "A&P" would look like, click on this link (file is a rich-text file), and it is in MLA format.

very important final note

In this, and other, lectures and samples you will see that direct quotations (not just summary) are widely used and that MLA-format parenthetical citations (not just designators) follow those quoted passages. This has not changed from English 101--you must use direct quotations and parenthetical citations in your discussions and essays if you want to get decent grades. This is true for all of your analytical and research writing in all classes.

Lecture 2 (continued): The Research Paper

how to write (and how not to write) a research paper (and why)

OK, I know. Some of you wonder why I brought you here. Many of you are fresh out of English 101 (or equivalent), and the Research Paper is a major component of English 101. It is an SLO; it is an absolute requirement. You probably pored over handbooks and/or the Purdue OWL cite, put together outlines, annotated sources, drafts leading up to the final paper with its parenthetical citations, its Works Cited page, and everything in MLA format.

Let me tell a chilling story (true story). The story is in the sidebar (the pinkish box) on the right.

Did you get a chance to read it (it was pretty long)? I do not want that to happen again. No, I can't make you read this (you may not have read the chilling story even), but I want to be able to say, at the end of the day, I did my best to help you all. So, here goes....

quick review i - when (and why) do we need to do research?

The quick answer is, "When the teacher assigns it." Yes, but why is the teacher assigning it; what's the point?

The practical answer is when we need specialized information for something we are doing (buying a car, building a deck, learning to sail, analyzing a difficult poem that has us stumped, preparing for a debate on whether or not the FDA should approve a new medication for asthma, trying to understand what Schroedinger's Cat thought experiment really means).

Let's get back to that debate. We may not want to debate about medication (which we will call Breathe-EZ). Big Pharma assures the public they absolutely need this stuff. It is going to revolutionize asthma treatments, and it is just a fraction of the cost of Flovent, Asmanex, Serevent, Brovana, ProAir, Spiriva, and a whole bunch of other medications (can you tell I JUST had to do some research to find specialized knowledge?). The FDA is not so sure, and they are looking at the clinical trial results, the potential risks-versus-rewards, the actual costs, and so on.

Vinny gets assigned the "This is a great medication" side of the debate, and Lily gets assigned the "We should not approve this medication" side.

Here are Vinny and Lily, prepping for the debate:

The day of the debate, both are about as prepared as could be reasonably expected. Neither is that thrilled with the topic, and both waited close to the day of the debate to begin, but away they go. First Vinny makes an empassioned and emotional plea for helping asthma sufferers. He shows a YouTube clip of someone short of breath using an inhaler. He states some marketing stats and very attractive costs from the pharmaceutical company, and he wraps up with a hearty, "Breathe-EZ" must be approved.

Vinny's done a pretty good job, and Lily is feeling worried. She can't really counter that YouTube video, and she doesn't have much evidence relating to the stats. But she starts gamely. She talks about the need for caution and lots of trials, and just then, the door opens; a scientific looking (?) man in a lab coat strides across and stands next to Lily at the lectern. He shows his credentials. He was a clinical trials researcher for two decades for Harvard Medical School, later moved into a research position for the Center for Disease Control for twelve years, and has recently been contracted independently to do investigative research specifically on asthma medications, including Breathe-EZ. He takes over the microphone (I forgot to mention there is a microphone). "Yes, I am very familiar with Breathe-EZ. In over sixty clinical trials involving nearly eight-thousand asthma sufferers, the medication has proven to work in less than 1% of the cases. Also, the side effects, which are alarmingly common, include greater difficulty breathing, heart and liver problems, and, frequently, death." He shakes Lily's hand (paw), and he exits.

Wow! Lily is feeling a whole lot better, and she continues on. She is not sure how to handle the cost issue. She mentions that these are really just projected costs and is sort of waving her hands (paws) when the door opens, and in strides a professional-looking woman in a business suit. She takes the mic and shares her credentials: she has worked in marketing, accounting, finance for twenty-seven years, and she is currently hired independently to investigate the cost claims made by the people who make Breathe-EZ. "The costs cited in their reports are costs to manufacture the medication. The numbers do not include the delivery system, packaging, marketing, distribution. They also do not include mark-up." She gives a knowing smile and continues, "The actual cost to the consumer will be in the neighborhood of seven to eight times more than other common medications on the market." She shakes Lily's hand (paw) and strides purposefullly back out of the room.

so who is going to win the debate and why?

Lily blew Vinny away, not because she knew much more about her subject and not because she is a better speaker (writer). She will win this debate because she has credible, authoritative, expert testimony (evidence) backing her up.

In a research paper your job is to find credible, authoritative, expert evidence (that you quote directly…more on that in a moment) to support your general argument because you are not an expert and because you do not have enough in-depth, concrete, specialized information about the subject.

credible, authoriwhatsis, blahblahblah?

Quite a lot of teachers will not let you use un-vetted websites for sources. If the site is a reputable news site (say, New York Times online), or if you search a library database for acaademic journals, that is generally considered fine. But whacko.com, biased.net, fanaticnut.org, and justanopinion.edu are not going to be acceptable. Wikipedia, Ask, Snopes and other such generic or wiki sources are also not usually acceptable for a research paper because the information is often user (not expert) supplied and often not fact checked. By the way, reputable print sources are good; print sources are good; print sources are good....

Let's go back to the debate and change the scenario just a bit: instead of the expert clinical researcher and the marketing/finance specialist, suppose that the first person to go to the microphone to help Lily out was Lily's mom: "Oh, she is such a great kid; you should believe her side of the debate." Umm...just may-be mom is a teensy bit biased. She may also know absolutely nothing about Breathe-EZ.

What if mom was followed by some random guy off the street who took up the mic and said, "I really don't know much about this subject, but I don't like medicines, so I'm on Lily's side."

Both of those testimonies are very weak. They are not going to convince many people. Vinny's touching YouTube clip will now probably give him the win.

quick review ii – what do we do with this evidence?

Well, a couple of things. First we need to position key quotations (again, more on that in a moment) from our sources into our papers where they logically fit. If we are writing a paragraph about cost-effectiveness of a medication, for example, then a quotation from an expert who has crunched the actual numbers belongs in that paragraph. The quotation comes from a source (article in a journal, news broadcast, etc.).

Then we need to make sure we acknowledge the source (otherwise we are stealing it and presenting it as though it were our own information, and that is the “p” word—plagiarism). Someone did a lot of work, and we are using their efforts to help make our own paper stronger (and, we hope, earn a higher grade), so we need to give the source information credit. We do that in two ways:

we include the appropriate information about the source on a Works Cited page

we include in-text citations every time we cite (quote from) one of the sources

I am not going to go into an exhaustive explanation of how to do a Works Cited page here. That information can be found in any writer’s handbook and in the MLA section of the Purdue OWL site. Just know that if you do not have a properly-done, complete Works Cited page, your research paper is going to be slammed. It is absolutely required.

NOTE: in the upcoming exercise, I have included a Works Cited page, so you will be able to see what one looks like. It does not represent all available source types, but it will give you the general idea. Get specific details for each type of source (film, newspaper article, lecture, personal interview, television news broadcast, etc.) in your handbook (if you have one) or on the Purdue OWL site.

the other kind of (required) documentation: in-text citations

This is unusually simple considering the Modern Language Association (MLA) had something to do with it; we place parenthetical citations after all direct quotations or other specialized information we get from our sources. Really, it is easy. REALLY…E-Z. Here is an example:

The creator, Ty Warner, “avoided large retailers and marketed Beanie Babies through smaller gift shops and collectible outlets, giving their products a certain luster in the eyes of collectors” (Aziz).

Simple! Following the direct quotation, which came from an article called “The Great Beanie Baby Bubble,” by John Aziz (don’t worry, we have a complete citation for this on the Works Cited page), we put the author’s last name inside parentheses. The reader can then flip back to that Works Cited page (which is organized alphabetically) and scan the entries for the one that begins with Aziz. The article title and other source information is there for the reader, and Aziz gets credit for his quotation.

If we go back to the debate, this is the same as acknowledging and giving particular information for the expert clinical researcher and the marketing/finance expert.

But wait! The handbook and Purdue OWL both have examples that use designators rather than parenthetical citations

Well, yes. Handbooks and Purdue OWL will show both sorts of in-text recognition. Here is what the Beanie Baby quotation could look like:

In an article called “The Beanie Baby Bubble,” by John Aziz, the author states that the creator, Ty Warner, “avoided large retailers and marketed Beanie Babies through smaller gift shops and collectible outlets, giving their products a certain luster in the eyes of collectors.”

This acknowledges the source, and it makes the parenthetical citation unnecessary.

So why bother with parenthetical citations

There are three reasons; the third is probably the most important from a practical standpoint:

it is the standard way of documenting material in the body of your paper

it is simpler than including the long designators

your teacher is looking for these in your paper; if they are not there, the teacher will think you do not know how to cite parenthetically, and your paper’s grade may go down; it may even not be accepted at all

Use parenthetical citations mainly. If you want to also use a few quotations introduced by designators that acknowledge the sources, that’s fine, but use parenthetical citations mainly

now about that “use direct quotations” thing…

Yes, I know. Every handbook and the Purdue OWL site explain/show that there are three types of information that must be documented:

direct quotations

specialized source information that is summarized

specialized source information that is paraphrased (whatever that means)

My students are require, whenever possible, to avoid the summary and paraphrase and just use direct quotations. There are a few reasons, p>When you summarize or paraphrase, there is a pretty good chance that you will misrepresent the source. If the information is highly specialized, you may not fully understand it, and your summary may not capture the idea and intent of the source completely. That is very common. If you use word-for-word quotations, the expert’s own ideas come through. Sure, the reader may have to look some things up, but it is much safer to use the exact language of the source.

If you summarize, then you are now responsible for the evidence; it is your wording and your interpretation. It is also less authoritative. Going back to that debate, it would be like Lily saying, “An expert in finance finds Breathe-EZ to be more expensive than it seems.” This does not have the impact of the expert striding up to the microphone and pronouncing that in her own voice.

Also, and this will show up in the exercise in a moment (exercise?), with summary and paraphrase, it is often hard to tell where the student’s voice (writing) stops and the source’s voice (information) starts. Let’s try the exercise, and this should become clear.

the exercise (please try each step; this is not hard, and it should reveal a whole lot)

I may not be watching you, but Suki is

The student paper on the rise and fall of the Beanie Baby craze used a mixture of direct quotations and summary, a mixture of source material introduced by designators and source material followed by parenthetical citations. Here Works Cited page was excellent (and is reproduced in the examples below). For this exercise, I am going to modify one body page of her paper in three different ways, and I want you to answer a couple of questions about each. Don’t worry. Nobody is grading you. I’m not there peeking over your shoulder. But please try this exercise. It won’t take long.

Click on the link below to open the first file (I have saved it both as .rtf and .doc; you should be able to open at least one)

Beanie Version One

Our main interest is with the body page, but you may want to look over the Works Cited page just to get an idea of what one should look like. Remember to read more detailed information on the various types of Works Cited entries in your handbook or on the Purdue OWL site; be sure to look at MLA style.

OK, now let’s get back to that body page. You can print it out, or you can highlight or underline parts of it on your computer (or highlight and make bold or whatever. Here’s what I want you to do (take your time):

locate and highlight all of the materials on this page taken from one or another of the sources listed on the Works Cited page

now determine which of the sources on the Works Cited page each item you highlighted came from

Did you notice something?

You can’t do either. There is no way to tell what is the students writing and what material comes from one of the sources, and there is no clue about which sources (if any) have been used. This could be entirely copied/pasted material (plagiarism); it could be entirely the student’s material (so it is not a research paper).

That is what the teacher sees too. That is going to earn a fail, and we do not want that.

Now click on the link below to open the second file (I have saved it both as .rtf and .doc; you should be able to open at least one)

Beanie Version Two

Let’s look at the revised body page. Again, you can print it out, or you can highlight or underline parts of it on your computer (or highlight and make bold or whatever. Here’s what I want you to do (take your time):

locate and highlight all of the materials on this page taken from one or another of the sources listed on the Works Cited page

now determine which of the sources on the Works Cited page each item you highlighted came from

What changed?

This time you could tell which sources were used because there were parenthetical citations, and those citations all corresponded to one of the sources listed on the Works Cited page. Good :)

However, there is stillno way to tell what is the students writing and exactlywhat material comes from one of the cited sources. Where does the student stop and the source material begin? It is possible that it is entirely copied/pasted material, and even though it may not be plagiarism, it would not be the student’s paper, so the student would not earn a grade; there is just no way to tell.

That is what the teacher sees too. That is likely to earn a fail, and we still do not want that.

Now click on the link below to open the third file (I have saved it both as .rtf and .doc; you should be able to open at least one)

Beanie Version Three

Let’s look at the revised body page. Again, you can print it out, or you can highlight or underline parts of it on your computer (or highlight and make bold or whatever. The drill is the same:

locate and highlight all of the materials on this page taken from one or another of the sources listed on the Works Cited page

now determine which of the sources on the Works Cited page each item you highlighted came from

YOU DID IT!

No, I promise I am not there looking over your shoulder, but I know you did it. You know where the student stopped, where the material from the sources began, which source each item came from.

The quotation marks made the difference; they marked off exactly what came from the sources. The parenthetical citations directly after each quotation told you which source each came from.

That is what the teacher sees too. You used your sources; you have a blending of your voice and evidence taken from the sources; you have acknowledged (documented) your source material.

the (nearly) final message(s)?

Try to use direct quotations whenever possible. Be sure you surround the quoted passages with quotation marks. Be sure you have parenthetical citations after your quotations (remember, you may use some designators, but mainly use parenthetical citations because it is standard, simple, and expected by your teachers). Be sure you have a proper Works Cited page.

About that Works Cited page: everything on it should be cited in the paper; if an item appears on the Works Cited page, you are saying you “cited” from it. Do not load up the page with things you did not use in the actual paper (note: a bibliography is different, but let’s not confuse things here).

All of the documented quotations, if they are from credible sources, will enhance your paper by providing specialized information and by supporting your own ideas with authoritative, expert evidence.

That is what a research paper is all about, and this information is true forever, for every class, for the real world after school when you write a research report (if you do); DO NOT FORGET THIS NEXT SEMESTER OR EVER. Yes, formats change (in psychology you use APA format, for example), and sometimes the nature of the research is different (in hard sciences you often are conducting hands-on, not book, research, and that is has its own chanllenges/requirements). But, for the most part, this information can be carried over throughout school and well into the real world.

When in doubt about any of this, ask your teacher. Some may require paraphrase. Some may have modified format requirements. It’s always safest to ask :)

about that works cited page

In other lectures (and on the Purdue OWL site) you have seen what the Modern Language Association (MLA) requires in terms of paper format (1" margins, double spacing, etc.) and in-text, parenthetical citations when you quote directly from a source. Those citations, though, do not really mean anything unless the reader knows what exactly you are citing from. A reader might want to read more on the subject or make sure you are using the material correctly in context of the larger source, so you have to create a Works Cited page for any essay that uses research material.

A lot of you have been putting together Works Cited pages for years, but I find some students are new to this. To further complicate things, MLA updated its Works Cited standards in 2016, so even students experienced in putting together a Works Cited page need to make some changes.

Here is an example of a 2009 vs. 2016 Works Cited entry; this is for a book with one author:

2009

Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid's Tale. New York: Anchor Books, 1998. Print.

2016

Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid's Tale. Anchor Books, 1998.

You probably noticed the 2016 version above is shorter. That is not always the case; some of the newer entries are longer, but there is still a kind of simplification-the punctuation is much simpler (nearly everything now will be either a period or a comma), things like city of publication is no longer necessary, and the media designator (Print, Web, DVD) is generally no longer included. One area that will make for longer entries is with websites; compare these two:

2009

"The Roswell UFO Incident Story." RoswellFiles. Web. 3 Dec. 2012.

2016

"The Roswell UFO Incident Story." RoswellFiles. www.roswellfiles.com/story.htm. Accessed 3 Dec. 2012.

(NOTE: this second version shows the "Accessed" date, but with the 2016 version, this is only included if there is no UPDATE date; yes, it can get confusing).why the changes?

Believe it or not, MLA is trying to simplify things both for themselves and for students/writers.

Prior to 2016, every time some new media came along (YouTube, Twitter, Instagram, SnapChat, etc.), Writers asked the MLA, "Well what do we do with THIS?" MLA (and the Purdue OWL site) had to get inventive and try to keep up with rapid changes and additions to kinds of sources students/researchers were now using.

This last convention they pretty much said, "We give up!" Instead of specific guidelines for each new kind of source, they went to a "container" model, basically:

Who. What. Where/When.

Most fancy punctuation was dumped in favor of periods separating Who, What, Where/When and commas separating items within each of those containers. Yes, they still have examples of interviews that look different from websites that look different from magazine articles, and so on, but the key requirements are now just basic logic and consistency with some room for variation based on what an instructor wants or requires. So, for example, if an instructor tells the class, "I know MLA did away with those media designators, but I like them, so I want to see Print after print sources and Television after TV sources and Web after web sources, then just do that.

The Purdue OWL site (and all updated handbooks) have examples of most every sort of source you would ever use, with instructions on what to do if one or more container elements is missing. In the web entry above for "The Roswell UFO Incident Story" above, for example, there are a couple of missing container elements: an author, a website update date. So those items are left blank, and you move on to the next element

final thoughts

Do not guess. Do not invent. Do not think you "just know" how to do a Works Cited page.

They are not hard to do; they just require you to look at examples and follow instructions. Always have the Purdue OWL site or an up-to-date (with 2016 MLA updates) college writer's handbook in front of you when you have to do one of these. Look closely; follow carefully.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)