context

One of the short story choices for Paper 1 is one of Kate Chopin's most famous stories. Probably her most famous work is a short novel, The Awakening, which shares many of the themes/ideas in "The Storm." If you read it, consider how this story might not work if it were set in contemporary Las Vegas. In considering that, you are being asked to take the story out of its original context.

In terms of fiction, context refers to the setting (time and place) and the sentiment (predominent thinking, tradition, social situation--norms) of that time and place. When you look at a story in context, you are possibly saying to yourself, "Well, things are not like that now, but back at the end of the 1800's in Cajun country..." and evaluating the story based on what the norms were then/there.

Here the effect of looking at a work in context or out of context (moving Calixta and Alcee to modern Las Vegas):

readers from the 1890's may have been shocked (they were). Don't worry, I'm not going to give away the plot here

Readers from the 21st century may still (or they may not) feel it is wrong, but it's probably not going to shock many readers given what we are used to watching on television or hearing on the news; after all, "What happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas"

Another story that does not work particularlly well out of context is "How to Talk to Your Mother." Ginny was born when women were not allowed to attend engineering school at UCLA. Women were generally expected to marry, have babies, and carry out domestic chores. My mom (born in 1928) was incredibly smart and well read, but she had no notion of going to university or starting a career--those were unusual pre-WWII. The real opportunities to have a choice (to choose the role of traditional wife/mother or become independent and career-oriented...OR BOTH) was happening right when Ginny was high school / college age. Imagine the different "voices" she had to struggle with--mom who only knew one way of life and was trying to help her daughter vs. the voice of a larger society telling women they could succeed in college and business. Let's take the story out of context and shift the events to 1980-2015:

It's not much of a story.

Is it OK to look at a work out of context? Is it fair? Of course it is. After all, new audiences relate the literature to their own situations. Still, to fully understand a work (or as much as possible), it is also important to try to put it in context, learn about the setting and sentiment surrounding the story when it was written.

another sort of context--the literary movement

There are lots of literary movements--the Romantic Movement (which is not about hearts and flowers), the Naturalist Movement (attempting to apply scientific objectivity to literature), the Absurdist Movement (reducing so-called meaningful interaction to non-sense), and so on. Writers who are inspired by the ideas and styles of a particular movement often give readers/writers some built-in "things" to consider/explore. For example, much of Edgar Allen Poe's fiction reveals elements of the Romantic Movement. Sometimes romance is involved, but that is not one of the characteristics of this movement. The Romantics were influenced by transcendentalism, by the restorative powers of nature, by the styles and subjects of (idealized) medieval writing and art, by the dark side (gothic manors, raven-haired temptresses, the supernatural).

One type of analysis has you exploring a work in relation to these characteristics associated with its movement (where, for example, do you find elements of the gothic and the supernatural in Poe's "The Masque of the Red Death"?), and it's not very difficult to do some quick research (look at your textbook, do some internet searches) to find out what the characteristics of a particular literary movement are.

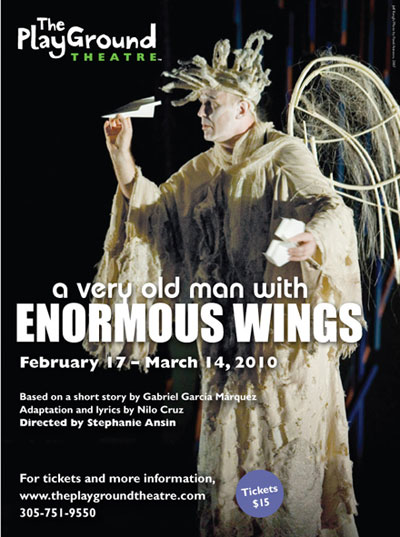

Gabriel Garcia-Marquez's (you may be reading one of his stories for Paper 1, though the topic is not to look at the work in context) and Laura Esquivel's (and others) works are closely associated with a movement called Magical Realism, combining some of the folklorico elements of Mexican/Central/South-American folk tales and the real political, social and/or religious corruption these authors found in their part of the world and satirized (held up to ridicule or bitterly attacked).

magical

The "magical" part is pretty easy to see in Marquez's stories. In one of his stories, "The Handsomest Drowned Man in the World," Esteban's corpse was retrieved form many days' submersion in the ocean; he is laid out prior to a funeral, and his body is not only NOT hideously decomposed or disfigured, he actually looks better and better as time goes by until his corpse is the handsomest man the women (and men) of the village have ever seen. Now that sort of unreality could easily happen in a folk or fairy tale, and readers would not blink. However, in Magical Realism, the reader is asked to accept that as a given fact of a realistic story. That takes some real willingness to suspend disbelief. You should have found many of these magical/impossible "things" in "A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings"--the story you were assigned.

The magical elements often make sense as symbols. Laura Esquivel's short-and-extremelly-popular novel Like Water for Chocolate), is peppered with lot of magical/impossible things that are very suggestive. In my favorite example, Tita is serving her quail in rose petal sauce to the family. She is in love with Pedro, but he is married to Tita's older sister, Rosaura. Tita's other sister, Gertrudis, is sitting between Tita and Pedro (yes, this is a complex seating arrangement, but you can see great opportunities to turn this into a novella :)

The rose petal sauce contains some of Tita's blood; while making the dish she held the roses to her breast, and the thorns pricked her; drops of blood fell into the sauce.

When the dish is eaten, something like an electric current passes between Tita and Pedro, and Gertrudis, in the middle, gets hit with it full force. She excuses hersef from the table and needs to cool of quickly. When she turns on the outdoor shower, but the heat from her body causes the wood to burst into flame. The scene continues from there (it gets better), but the idea is already clear: 1) the unrequited love has dripped into the sauce and is made physically real; 2) Tita is able to communicate her feelings through her gift--her cooking; 3) Tita's passion is so intense that it inflames others who expeirence it even second hand. That's pretty neat!

realism

The "realism" part is often got at through our understanding of the magical elements as symbols.

In Like Water for Chocolate certain traditions are being satarized (attacked) while others are not. One tradition, the wedding, is looked at differently in different chapters of the novel. When Pedro marries Rosaura, a semi-forced union based on a tradition, not on love or respect, Tita's heart is near-broken (after all, she and Pedro love one another). Tita is expected to make the wedding cake for the reception, and as she folds the batter, she cries bitter tears into the mix. The day of the wedding, this lovely cake arrives, but all who eat it spew it up; they cannot stomach the cake just as this wedding created from a devisive tradition cannot be stomached.

was that a hint?

If you are choosing "A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings" for Paper 1, you might want to consider if it too is a satire :)

literary elements

Most Literature Anthologies (English 102 textboooks) focus on the various elements of fiction (plot, character, setting, etc.) and how these often (though not always) add to an understanding of the work you are reading. In this week's reading, for instance, the setting (where and when the story takes place) is centrally important. As noted above, if Calixta and Alcee met in Las Vegas in 2010, the story would have almost no shock value and little to think about. The storm in the story is a literal event (plot), but it also is suggestive of what is going on with the characters (symbolism).

Here's another example: in "All About Suicide," the re-re-re-telling of the plot with variations is important to at least one interpretation of the story. Here we are forced to notice the plot because it is 1) a repeated pattern and 2) weird. So the look-for-patterns-and-peculiarities thing is still helpful, even when focusing on individual literary elements.

Simply, there are a lot of elements that make up a story; sometimes they are significant, and sometimes they are not. Not all stories have symbolism, for example. I would be hard pressed to find any symbolism in "A&P," for example. There is a ton of symbolism in "How to Talk to Your Mother," though.

a quick look at some of the literary elements (and there are a lot, so it's not that quick)

Plot

The plot of a story is simply the events that take place in the story. Most people read only for plot--but you now know to look for theme, too. And often, clues to the author's intentions can be found in the plot.

For example, pay attention to beginnings and endings of stories, and ask yourself questions: Why did the author choose to begin the story with this event? Why choose to end it with that event? What has changed between the beginning and the end? "A Rose for Emily," for instance, begins when Miss Emily is old and then moves back and forth in time. Why wouldn't Faulkner choose to begin when Miss Emily was younger, and then work his way up to her death? Has anyone in the story changed between the beginning and the end? If so, how?

Look also at the stages in all the important changes. What happens to change things or people? Why do you think the author chose to take this course of action? In "Gryphon," for example, how does the narrator change? What does he learn? How does he learn these lessons, and how does he act on them?

Look for events, people, and/or circumstances that work against the action of the story. In "The Things They Carried," for example, the narrator tells us what happens to the soldiers--but he also repetitively tells us what they carry, and this slows down the story. Why would O'Brien choose to include all this information? Why not just tell us what happened?

Look for characters, events, and details which seem to make no contribution to the plot or movement of the story, and ask yourself why they are there. In Faulkner's "A Rose For Emily" what is the purpose of Toby being there? Why are we listening to the testimony of the wife's mother in Akutagawa's "In a Grove"?

Character

Characters in books and stories can function in two ways: they can be individuals, with unique characteristics, habits, quirks, and personalities, so that they seem like real people; or they can be "types"--that is, they can typify or represent something larger than themselves. The best characters do both.

In a story, the main character is called the "protagonist." The protagonist's opponent is the "antagonist." The antagonist is usually another person, but in some stories it is an animal, or a spirit, or even a natural force. Figuring out which character is the protagonist can help you to interpret the story's theme. For example, in "A Rose for Emily," we might say the protagonist is Emily--or we might say the protagonist is the town. If we choose Emily, we might see the story's theme as having to do with fear, loneliness, or mental illness. If we choose the town, we might see the story as having to do with social isolation or social class.

Some characters are "flat"; others are "round." Flat characters may play a small or a large role in a story, but they experience no change or development throughout the course of the story. Round characters change, grow, develop. (This does not make round characters superior to flat characters; it simply means they serve a different function in the story, depending on the author's intention.) In "The Storm," for instance, the husband, Bobinot, is flat; we do not see him experience any growth or development during the story. But the narrator, his wife, is round; her experiences change her.

Often, the names of characters are revealing. Authors are usually careful to give their characters appropriate names. Charles Dickens, for example, in Nicholas Nickleby, names a schoolmaster "Mr. Choakumchild"; right away, we know that Nicholas is in for a rough time at this school. Sometimes, the meaning is more subtle. In Herman Melville's Moby Dick, the doomed captain is named Ahab, after a Biblical tyrant who came to a bad end.

And last, examine the character's motivation: what makes him act as he does? This is important especially if he acts in an unexpected or unusual way. In "Rose for Emily," for example, why does Homer court Miss Emily when he is gay? Answering such questions can help you arrive at an interpretation of the story.

Setting

The setting of a story is simply where it is placed, geographically and in time. Often, an author will use the setting to create a mood ("It was a dark and stormy night..."). Asking questions about setting can also help you see the themes.

Ask yourself where and when the story is set. "The Storm," for example, takes place at the turn of the century. Is that important to the events and characters in the story? Would the story be any different if it were set in the present time? And the story takes place Louisiana, during a storm; why did Chopin choose to set her story in that particular time and place? How would the story be different if it were happening on a sunny day?

Asking yourself questions about how the setting affects the plot, the characters, the relationships between characters, and the mood may help you figure out the theme(s) of the story.

Point of View

All stories have a narrator, someone who tells the story. The narrator is not the same as the author. The narrator is a character the author has invented; through the narrator, the author manipulates the way you see the events and the other characters.

There are different types of narrators. Each has its advantages and disadvantages, and the author chooses the type which will best help him tell the story and present the themes.

The first person narrator is a participant in the story. He or she is telling the story: "I went to the store," or "I saw the events happen." The narrator may be a major character, as in "A&P," or a minor one, or an unusual one as in "Rose for Emily."

The third person narrator is not a participant in the story. He stands outside the story and reports on the events: "He went to the store," or "She saw the events happen."

There are several types of third person narrators.

- A "third-person omniscient" narrator is "all-knowing"; he can see what all of the characters are doing and thinking, as in "The Things They Carried" or "This is What It Means to Say Phoenix, Arizona."

- A "third-person limited omniscient" narrator is all-knowing, but only about one character; he can see everything that character is doing or thinking, as in "A Good Man is Hard to Find."

- A "third-person objective" narrator can't tell us anything that the characters are thinking; he can only report on their actions. The only story we're reading for this class that comes close to having an objective narrator is "A Clean, Well-Lighted Place", but even that slips into third-person omniscient in the second half of the story.

The attitudes and opinions of the author are not necessarily the same as those of the narrator. In fact, many authors deliberately create characters nothing like themselves in order to create a conflict between what we are told and what we are supposed to believe.

A story may be told by an innocent or naive narrator, a character who fails to understand all the implications of the story he is telling. For example, one of my neighbors is a six-year-old girl named Rachel. She knows everything that happens in the neighborhood, and when I moved in, she told me about all of the people on my street: this person has two cats, that person is a truck driver, "...and the man across the street wears a suit to work, and his wife stays home, and the mailman comes to their house everyday for lunch." Now, any adult can draw the obvious conclusion, but Rachel doesn't understand the implications. Thus, she is an "innocent" or "naive" narrator.

A story may also be told by an unreliable narrator, whose point of view is deceptive, deluded, or deranged, as in Edgar Allen Poe's "the Tell-tale Heart".

Some less-common, but quite interesting, points of view are Stream of consciousness, Interior Monologue, Central Intelligence, and so on. If you look up Poiint of View online or in a dictionary of literary terms, you will find much more on the subject

Any point of view has its advantages and disadvantages, from the writer's standpoint. So when you are reading, ask yourself why the author chose to use this particular point of view. What do you know that you might not have known if the story had been told from another point of view? How would the story be different if another character had narrated the events?

Style, Tone and Language

Each author has his or her own style, his or her own way of using language and details to express ideas. Style, too, can reflect theme. Tone is the author's attitude towards the material: the tone might be direct, didactic (preachy), comical, ironic. This last one, ironic, is important to look out for. If you cannot tell when a writer is satirizing (mocking)his subject, you might mistake the attack on the subject as an endorsement of the subject.

Ernest Hemingway, for example, in "A Clean, Well-Lighted Place," uses many short, sharp sentences and gives few descriptive details. Paragraphs consist of just a few sentences. Even the lines of dialogue are short and clipped:

"Last week he tried to commit suicide," one waiter said.

"Why?"

"He was in despair."

"What about?"

"Nothing."

"How do you know it was nothing?"

"He has plenty of money."

Even in the longer sentences, the words are short and hard-sounding: "The waiter poured on into the glass so that the brandy slopped over and ran down the stem into the top saucer of the pile."

This style helps express the themes of the story, one of which is the isolation of individual people from each other, and their loneliness. These people live in a hard world which provides little comfort, even in language.

In "A Rose for Emily," William Faulkner also explores the theme of isolation, but he emphasizes Emily's alienation by using style to provide a sense of abundance from which Emily is excluded. Many of Faulkner's sentences are long and include several ideas; the words flow smoothly and lazily, matching the pace of life in the town; and the narrator is "We," the people of the town:

When Miss Emily Grierson died, our whole town went to her funeral: the men through a sort of respectful affection for a fallen monument, the women mostly out of curiosity to see the inside of her house, which no one save an old manservant--a combined gardener and cook--had seen in at least ten years.

As you can see, style and tone are closely connected.

Symbol

Another tool writers use to help establish a thesis is symbolism. A "symbol" is a thing which suggests more than its literal meaning. For example, a rose usually stands for love; a sign of the skull and crossbones stands for poison.

In literature, most symbols aren't so simple; they usually don't "stand for" any one idea. Instead, they suggest or hint, or draw attention to an idea. They can mean more than one thing, and they can be interpreted in different ways by different readers.

In John Nichols' novel,

The Milagro Beanfield War, one of the characters, an old man, sees an angel. But it is not your conventional angel. This is an old, battered, mangy, cranky coyote with one broken wing and a crooked halo. And he makes it plain that he's angry about being assigned to protect these people in this tiny town.

Now, John Nichols could have created a beautiful, white-robed angel with a shining halo, but he chose not to. What does Nichols want to imply about the people of the town? What qualities and attributes do coyotes have that the people of the town might also have? Coyotes are scavengers; they can survive anywhere; they may not be pretty, but they are very smart; and they are tough, sneaky, and creative. You can see what Nicjols is implying about the townspeople.

Characters can be symbolic, too: Miss Emily, in "A Rose For Emily," represents a rapidly fading way of life; Homer Barron represents the new century and its new ways.

To find symbols, look for references to objects that are repeated; look closely at references to objects that aren't necessary to the story (Miss Emily's invisible, ticking watch is mentioned twice, for example, when it is completely unimportant to the plot). Symbols are often found at the beginning or end of a story, or make up part of the title. And don't skip the descriptions: often, symbols are found there.

Allegory

An allegory is a story which has two levels of meaning, one literal and one symbolic. Each event, character or object symbolizes one single idea. The medieval play Everyman is an allegory: its characters are named such things as Kindred and Good Deeds, and stand for virtues and vices. The play is not at all ambiguous; it is meant to teach a clear lesson to its audience.

A "fable" is a type of allegory, except that the characters are animals with human traits. As in an allegory, there is a clear moral. The most famous fables are by Aesop, and each has a moral stated explicitly at the end.

The following fable by James Thurber is humorous, but is still intended to make a strong point. It was published just after World War II.

The Rabbits Who Caused All the Trouble

Within the memory of the youngest child there was a family of rabbits who lived near a pack of wolves. The wolves announced that they did not like the way the rabbits were living. (The wolves were crazy about the way they themselves were living, because it was the only way to live.) One night several wolves were killed in an earthquake and this was blamed on the rabbits, for it is well known that rabbits pound on the ground with their hind legs and cause earthquakes. On another night one of the wolves was killed by a bolt of lightning and this was also blamed on the rabbits, for it is well known that lettuce-eaters cause lightning. The wolves threatned to civilize the rabbits if they didn't behave, and the rabbits decided to run away to a desert island. But the other animals, who lived at a great distance, shamed them, saying, "You must stay where you are and be brave. This is no world for escapists. If the wolves attack you, we will come to your aid, in all probability." So the rabbits continued to live near the wolves and one day there was a terrible flood which drowned a great many wolves. This was blamed on the rabbits, for it is well known that carrot-nibblers with long ears cause floods. The wolves descended on the rabbits, for their own good, and imprisoned them in a dark cave, for their own protection.

When nothing was heard about the rabbits for some weeks, the other animals demanded to know what had happened to them. The wolves replied that the rabbits had been eaten and since they had been eaten the affair was a purely internal matter. But the other animals warned that they might possibly unite against the wolves unless some reason was given for the destruction of the rabbits. So the wolves gave them one. "They were trying to escape," said the wolves, " and, as you know, this is no world for escapists."

Moral: Run, don't walk, to the nearest desert island.

Thurber is obviously criticizing the United States and other European countries who failed to help the Jews when Hitler began persecuting them. The wolves are the Nazis, the rabbits are the Jews, and the other animals are the other countries.

literary criticism

Here is what literary criticism is not: it is not the same as a book review. When you read popular articles on the latest Dan Brown novel in a magazine like People or an online newspaper such as The L.A. Times, you are likely reading a book review. This is just a quick summary, maybe some character sketches, and a "thumbs-up/thumbs-down" (whether or not the writer liked the book). Plot summary and personal opinion are not what you are looking for when you use secondary sources; it's one reason Wikipedia, Snopes, Ask, SparkNotes, etc. are not acceptable sources for your writing. They are basically cheat sheets that tell you what to think (and they often encourage plagiarism--a very bad thing).

Literary Criticism (the English call it "Appreciations," because the word criticism sounds negative, and that is not generally the case. If it makes it easier for you to understand, just call it Literary Analysis), is often published in literary journals (not popular magazines/newspaper). That is why using the Literary Criticism database at the library is going to be one of your best sources. Or wander the reference section in the physical library; you can browse volulmes of Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism or Cyclopedia of World Authors or The Explicator and so on. Chat with the Reference Librarian to get some help if you are lost. NOTE: public libraries generally do not have much academic reference material; use a college/university library/database for this.

There are many kinds of articles (some with feminist slants, some relating works to psychological research, some exploring Marxist economic theory in relation to what happens in a work, some placing works within the context of a literary movement, some focusing on literary elements, and so on), and you might want to sample some alongside the readings you are being assigned for this class. Visit the library's online databases (there are some just for literary criticism, or visit the reference section of any college/university library to look at print sources.

This may give you ideas of your own about different ways to approach a story, poem, play, novel.

If nothing else, this should reinforce the idea that there is no single right way to interpret a work of literature.

NOTE: it is absolutely OK to use Literary Criticism in your writing, but if you do, be sure you 1) have a Works Cited page (done correctly in MLA format) that credits all sources, and 2) that you quote directly and follow those quotations with parenthetical citations (done correctly in MLA format) crediting the source for each quotation you use. If you fail to credit an outside source, yep, that's plagiarism :(

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)