ok, so you know how a lot of teachers don't like you using wikipedia sources?

Well, yes, I am one of those teachers, but I am also realisting enough to use those sources when I am not doing formal research. I came across an interesting note on time capsules on Wikipedia, which included:

According to time capsule historian William Jarvis, most intentional time capsules usually do not provide much useful historical information: they are typically filled with "useless junk", new and pristine in condition, that tells little about the people of the time. Many time capsules today contain only artifacts of limited value to future historians. Historians suggest that items which describe the daily lives of the people who created them, such as personal notes, pictures, and documents, would greatly increase the value of the time capsule to future historians.

If time capsules have a museum-like goal of preserving the culture of a particular time and place for study, they fulfill this goal very poorly in that they, by definition, are kept sealed for a particular length of time. Subsequent generations between the launch date and the target date will have no direct access to the artifacts and therefore these generations are prevented from learning from the contents directly. Therefore, time capsules can be seen, in respect to their usefulness to historians, as dormant museums, their releases timed for some date so far in the future that the building in question is no longer intact.

Historians also concede that there are many preservation issues surrounding the selection of the media to transmit this information to the future. Some of these issues include the obsolescence of technology and the deterioration of electronic and magnetic storage media (known as the digital dark age), and possible language problems if the capsule is dug up in the distant future. Many buried time capsules are lost, as interest in them fades and the exact location is forgotten, or they are destroyed within a few years by groundwater.

Archives and archival materials, including videos, might be the best types of time capsules, as long as the medium can still be used, or the data can be read by the latest technologies and software.

Wow! Pretty harsh. And if you looked ahead to this week's discussion, you certainly now may be wondering we are going to be creating time capsules. Consider it a step, an easy, entry-level gathering of "stuff" that potentially tells a story about a group of people in a particular time and place. Also consider just how hard that is.

but before we get to that step, consider just how little "found stuff" reveals about culture/civilization

Consider the message in a bottle, a sort of time capsule containing a piece of paper with writing on it (sort of like a litereature textbook shoved in front of you). You are wandering along a beach, and you see a corked wine bottle on the shore among kelp and driftwood. Looking closer, you see there is a note inside. You are curious, and so you uncork the bottle, fish out the note, unroll it, and read: "I do not think that I can endure this much longer."

And that's it. That's the entire note.

There seems to be a rich, dramatic story there, but what is it? This same kind of problem occurs in Ruth Ozeki's novel Tale for the Time Being, where a journal from a Japanese teeager washes up on the shore in the Pacific Northwest. A couple can only guess at the parts of this girl's life not included in the little book. And then there's this book:

David MacCaulay has won numerous award as a children's book writer/illustrator, starting with his book Castle. I still refer to his simple, illustrated The Way Things Work from time to time. In 1979 he branched out and directed a book towards older readers. At its heart there were still delightful illustrations, but the text was actually a thought-provoking satire of archeology and its limitations.

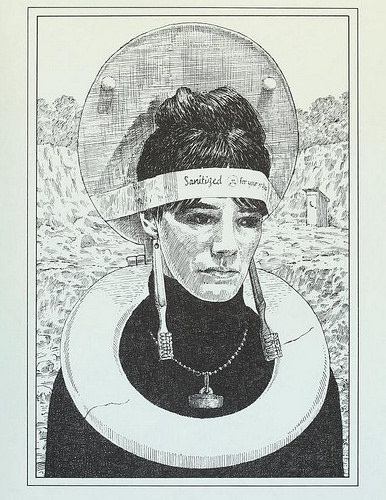

This week's reading is just an excerpt from his book, but it shows you that a chamber filled with ancient things that are far-removed from contemporary culture are mysterieous found objects if there is no context/background for understanding those things. The archeologist (named after the discoverer of King Tut's tomb in Egypt) believes he has uncovered a royal burial chamber filled with religious relics that reveal a great deal about this ancient desert culture. They construct a "story" about that civilization that is, well, off. Here is their recreation of what the priest/priestess must have looked like based on items found in a font room:

It's pretty funny (I particularly like the toothbrush earrings :), but it makes one wonder if a lot of what we believe about ancient cultures is accurate or even close to hitting the mark.

And we get the gag. Why? Because the "tomb" they have unearthed is a flea-bag motel in the desert from the 20th Centurey; we are familiar with the use of toilet seats and toothbrushes. But imagine archeologists 3,000 years from now. The odds are, especially given the incredibly-rapid rate of change in the 21st centure, that their world will be so very different from ours that these will be weird, arcane, exotic doo-dads that make no real sense to them. Of course the implication is that perhaps a lot of our understanding of the past is just as "made up" as the recreations in MacAulay's book.

How DID Howard Carter know, in 1922, what all of the items he unearthed in King Tut's tomb were, what they represented, how they reflected ancient Egyptian culture?

along comes the rosetta stone

No, this is NOT the Rosetta Stone; it's the Lycurgus Cup (very very neat :)

If you happen to be wandering through the British Museum, do stop to take a look at The Rosetta Stone (and The Lycurgus Cup, OH, and the mummy in the floor).

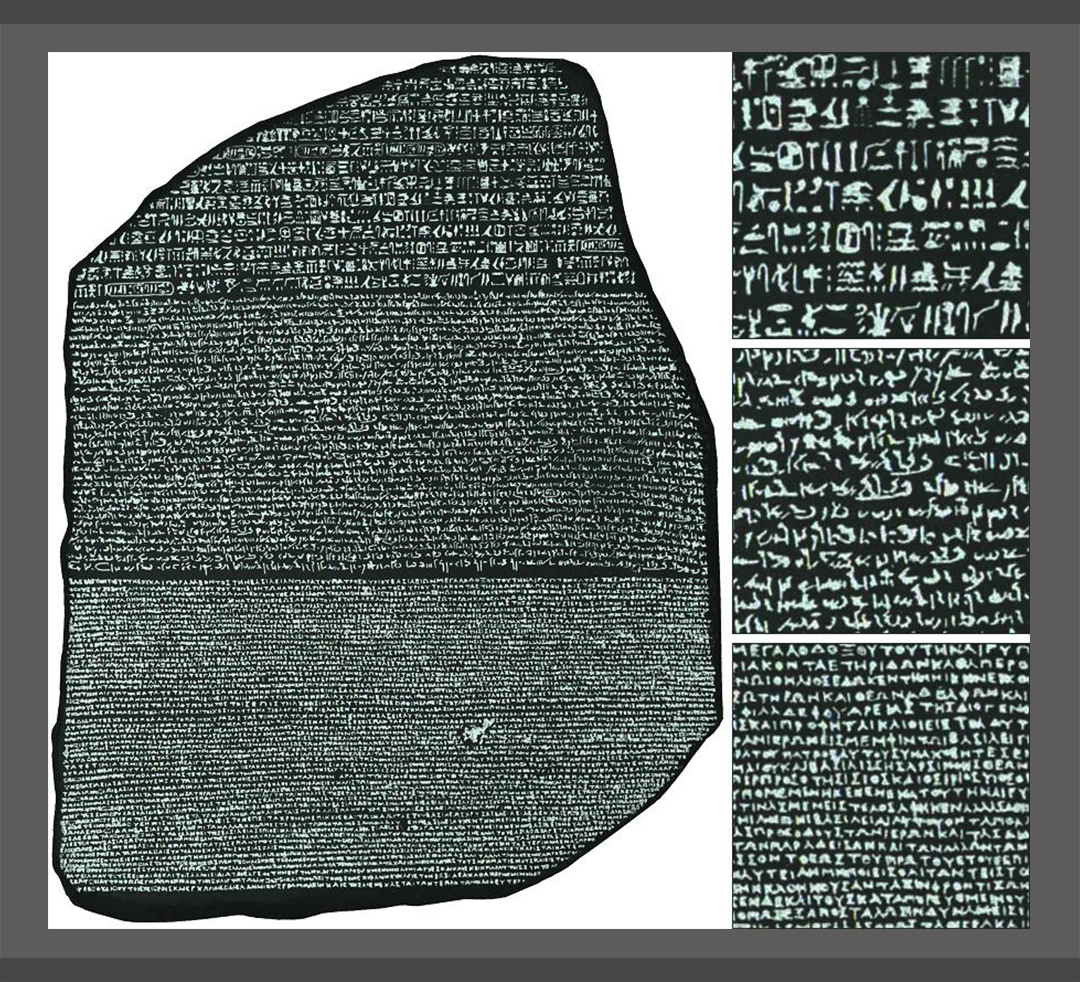

OK, OK, here's the Rosetta Stone

Prior to the French discovering this as they were doing construction in Egypt in the 1700's, nobody (living, at least in the west) understood Egyptian heiroglyphics, and so all of those inscriptions in the discovered pyramid burial chambers were just gibberish. This stone has information transcribed in three scripts (one of these is coptic, which was known, and one is heiroglyphics, which was not). The message is repeated in each script, and so comparing the coptic to the heiroglyphs allowed scholars to unlock the meaning of this new (well, old) language. Can you see why the language-learning company called Rosetta Stone took that name?

Here (again) is the point: without context, without the language, the history, the story to put "things" in some logical context, the things are just things; they do not communicate an idea or reveal the nature of a culture/civilization. Keep this in mind as you do the various steps for this semester's Station Eleven project. Yes, you want to find a collection of novel, related things, but they also need to reveal something, have an engaging background/history/story. For now, let's deal with things and imagine what they might reveal about a culture, OUR culture. Let's start with...

the time caspsule

The hoped-for goal of a time capsule is to preserve some iconic items from a particular place/time, have them survive X number of years (possibly indefinitely), and have future generations discover and open the capsule to see just what some aspect of a culture was like in their past. It's a way of passing on our story, what is significnt to us. And, of course, what is significant to one person (a cell phone with the Fortnite mobile app), may be mindless junk to another person, and that is fine; we are not all the same person, and, really, to get a reasonable picture of a time/place/culture/civilization, and whole lot of different things would need to be unearthed from many different time capsules (or from many different archeological digs).

The above pictures show the contents of a recently opened soldier's time capsule from WWI, a watertight stainless steel time capsule that should protect its contents for quite some time, and the sort of do-it-yourself time capsule that can be assembled easily and inexpensively. NOTE: the time capsule you are creating (imagining) for this week's discussoin will be like this last, do-it-yourself one.

What you could put into such a "capsule" to send off to fellow humans 100, 1000, 10000 years into the future. How would it reveal what we were like in the 21st century? How might it be misinterpreted? What sorts of things could be included to give them a better chance at understanding the contents?

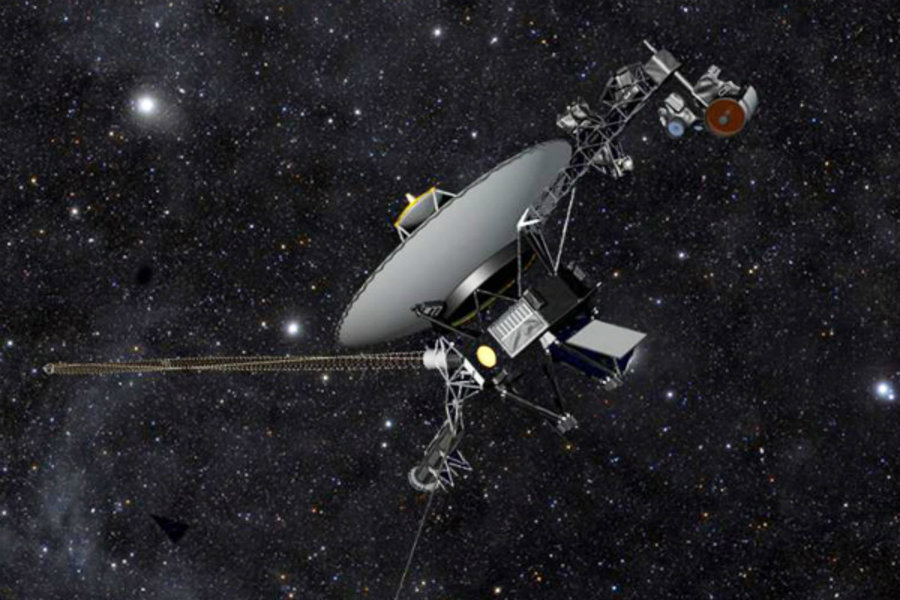

Consider NASA's Voyager program.

Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 were sent off into deep space in 1977. On board each was a Golden Record that NASA compiled (the group deciding what sights, sounds, equations, etc. would be included was headed by Dr. Carl Sagan). There was some controversy (one image of a sketch of a naked man and woman was too shocking (look it up; you will not be at all shocked, but that was the 1970s; remember, time/place--setting--is important), and it was eventually replaced by silhouettes of a man and a woman. If you would like to see more details of what was included on the record click on the JPL NASA site here. It's really pretty interersting to see what they thought best represented humans in the 20th century, what they though alien races would understand.

And let's jump back to the Wikipedia criticism of time capsules (Voyager really is just a space-faring time capsule, well, among other things) we read at the beginning of this lecture. Can any randomly-selected group of items (even images and sounds) truly communicate culture? Is there enough context included? Would an alien race (perhaps composed entirely of amonia) relate in any way to the record? Would they have the means to "play" the record?

To address this latter concern, the scientists did include a good deal of math and physics notations on the disk. But even that assumes that an alien race would make some sense of human systems. That seems pretty arrogant of humans, no?

FINAL NOTE FOR STAR TREK FANS: for this I am going back to Wikipedia where we have a neat summary of the plot of Star Trek: The Motion Picture - the first Star Trek movie from 1979 (two years after Voyager).

MASSIVE *SPOILER* ALERT!

In 2271, a Starfleet monitoring station, Epsilon Nine, detects an alien force, hidden in a massive cloud of energy, moving through space toward Earth. The cloud easily destroys three of the Klingon Empire's new K't'inga-class warships and the monitoring station en route. On Earth, the starship Enterprise is undergoing a major refit; its former commanding officer, James T. Kirk, has been promoted to Admiral and works in San Francisco as Chief of Starfleet Operations. Starfleet dispatches Enterprise to investigate the cloud entity as the ship is the only one in intercept range, requiring its new systems to be tested in transit.

Citing his experience, Kirk takes command of the ship, angering Captain Willard Decker, who had been overseeing the refit as its new commanding officer. Testing of Enterprise's new systems goes poorly; two officers, including the Vulcan Enterprise science officer Sonak, are killed by a malfunctioning transporter, and improperly calibrated engines nearly destroy the Enterprise. Kirk's unfamiliarity with the ship's new systems increases the tension between him and Decker, who has been temporarily demoted to first officer. Commander Spock arrives as a replacement science officer, explaining that while on his home world undergoing a ritual to purge all emotion, he felt a consciousness that he believes emanates from the cloud, and was unable to complete the ritual because his human half felt an emotional connection to it.

Enterprise intercepts the energy cloud and is attacked by an alien vessel within. A probe appears on the bridge, attacks Spock and abducts the navigator, Ilia. She is replaced by a robotic replica, another probe sent by "V'Ger" to study the crew. Decker is distraught over the loss of Ilia, with whom he had a romantic history. He becomes troubled as he attempts to extract information from the doppelgänger, which has Ilia's memories and feelings buried inside. Spock takes a spacewalk to the alien vessel's interior and attempts a telepathic mind meld with it. In doing so, he learns that the vessel is V'Ger itself, a living machine.

At the center of the massive ship, V'Ger is revealed to be Voyager 6, a 20th-century Earth space probe believed lost in a black hole. The damaged probe was found by an alien race of living machines that interpreted its programming as instructions to learn all that can be learned and return that information to its creator. The machines upgraded the probe to fulfill its mission, and on its journey, the probe gathered so much knowledge that it achieved consciousness. Spock realizes that V'Ger lacks the ability to give itself a purpose other than its original mission; having learned what it could on its journey home, it finds its existence meaningless. Before transmitting all its information, V'Ger insists that the Creator come in person to finish the sequence. Everyone realizes humans are the Creator. Decker offers himself to V'Ger; he merges with the Ilia probe and V'Ger, creating a new form of life that disappears into another dimension. With Earth saved, Kirk directs Enterprise out to space for future missions.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)