"the book is always better than the movie," or is it?

Most people who've been around me for any length of time know that I'm book-ish.

Right off, let's not confuse this with Kindle-ish or Nook-ish; I don't want to read my books on an iPad or flip phone (though I do sometimes listen to audiobook when I drive). I like BOOKS--the things with paper and covers, with weight and heft and decoration. I did not always particularly like books, unless you count 10-cent Detective and Justice League America comics as books. I'm an ex-physics major, one who wanted to shoot rockets to far-flung planets, turned English major my second year of college. Now I'm book-ish.

I love thin volumes of Eliot and the latest Preston and Child pot-boiler. My Complete Annotated Sherlock Holmes (two-volume boxed edition) sits near The Labyrinths of Reason and John Steakley's outer-space military classic Armor. Books are wonders; they are other times and places, ideas and states of being in compact form.

But that is not to say I'm not movie-ish too. I still remember my folks taking my sister and me to Centinela Drive-in when I was eight to see Dinosaurus!. Casey and I were dressed in our pj's in the back of the Olds 88 station wagon. I think my folks expected us to fall asleep, but I was transported to an primeval island watching a mechanical crane duke it out with a T-Rex. I loved it.

By college I was watching movies at the SDSU film club, driving back to L.A. to see Monty Python and the Holy Grail then Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow-up at L.A.'s Film-Ex, staying up late to catch Luis Bunuel's The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie at the Fox Venice then Peter Watkins's Privilege at the Nuart.

Books and films both have the power to engage and entertain, to take readers/viewers to other places and times.

books are different from movies

The difference is not so much where literature and film take you; the difference is in the means of transportation, the media.

Reading is an active medium; film is passive. Now that sounds about as counter-intuitive as anything could. The book or story is fixed, changeless; a movie got that name because it moves. But the means of communication--tranferring an image, idea, feeling from one person to another through a medium--is at the heart of this. Words are abstractions; they have only as much meaning as we allow them, and we have to do some work to turn the shapes (letters, words, sentences) into things. We have to be active in the communication process.

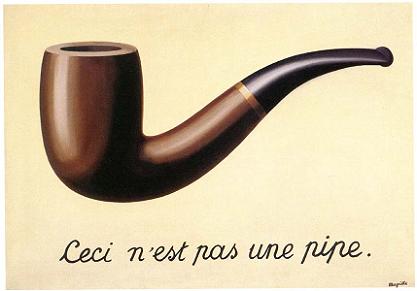

Rene Magritte suggested this when he painted the image hanging at the LA County Museum of Art:

The joke/truth of the thing is that it is not a pipe; it's a picture of a pipe. The medium (painting) reminds us of a pipe. It also has a huge advantage over the word pipe because it passes on a fairly specific image of a pipe. Most viewers will have a very similar sense of pipe-ness from this picture. The work, however, might cause someone to imagine a long, thin oriental pipe or chunky Meerschaum or even a length of plumbing.

The joke/truth of the thing is that it is not a pipe; it's a picture of a pipe. The medium (painting) reminds us of a pipe. It also has a huge advantage over the word pipe because it passes on a fairly specific image of a pipe. Most viewers will have a very similar sense of pipe-ness from this picture. The work, however, might cause someone to imagine a long, thin oriental pipe or chunky Meerschaum or even a length of plumbing.

The reader has to take the abstraction and imagine some sort of pipe, and different readers will have different images in their heads. It's inexact, but the rewards are great if a reader is willing to put in the effort. Stephen King leads us to an idea of a monster dog in Cujo, but the real fierceness, massiveness, menace of Cujo is created by the reader. The words energize the reader to bring the monster to life, and the scariness is only limited to the reader's imagination.

Cujo is a great example here. The "book is better than the movie" quotation seems often true when it comes to translating Stephen King books to film. In the movie, Cujo is a big, floppy, goofy-looking dog; it's hard to imagine him raising the hair on the back of your neck. It just doesn't work.

Ridley Scott's Alien, however, works. H.R. Giger's imagination is creepy, and the designers had the sense to change the monster from one disturbing form to another--all playing on general fears of bugs, snakes, fangs, dangerous technology, disturbing fluids. The French call what a director does "realisation" (to make real for the audience). We sit and let sights and sounds wash over us, and the success/failure of the film depends on the director, actors, set designers, special effects artists, sound technicians, camera operators, editors, and so on--that is a lot of work that we don't have to do, and if it's done effectively, with thought and style, the movie can be as effective and memorable as a book.

lets take a look

The Guardian, one of Britain's long-published newspapers, ran a human interest feature in its Entertainment section, the subject, the ten best hanogover scenes in literature and their translations to film. No, the movies The Hangover and Hangover: Part II were not in the running. It pleased me to see that their number one was also my number one, a scene from Kingsley Amis's angry-young-man novel Lucky Jim:Dixon was alive again. Consciousness was upon him before he could get out of the way; not for him the slow, gracious wandering from the halls of sleep, but a summary, forcible ejection. He lay sprawled, too wicked to move, spewed up like a broken spider-crab on the tarry shingle of the morning. The light did him harm, but not as much as looking at things did; he resolved, having done it once, never to move his eye-balls again. A dusty thudding in his head made the scene before him beat like a pulse. His mouth had been used as a latrine by some small creature of the night, and then as its mausoleum. During the night, too, he’d somehow been on a cross-country run and then been expertly beaten up by secret police. He felt bad.

Others have explained the genius of the writing; Misha Adair from Melbourne has a nice write-up on her blog here: Kingsley and Martin Amis on The Hangover

But what's most relevant for us is that this writing, filled with hyperbole and litotes, with wild imagery and inventive comparisons, can't easily be represented on film. In fact, there is a still shot from the film version of Lucky Jim showing Ian Carmichael nursing his throbbing head. The movie is fun and funny, but the image does not pack in the details that Amis's writing does. The picture is not, in this case, worth 1,000 words.

Now fire up the YouTube video clip below.

A New Hope

This opening (following the crawl) of the first (or fourth depending on how you're figuring) Star Wars movie amazed audiences of 1977, and it still holds up over forty years later. Yes, to do it justice we need to be in cushiony, high-backed chairs looking up at a large-aspect wide screen with Dolby Surround Sound and the (then new) Lucasfilm THX system. The postage-stamp-sized clip on your computer doesn't make the room rumble, and the star cruiser doesn't start from its pinpoint prow to grow into an image that completely fills your field of vision. But this movie took full advantage of the audio-visual potentials of the last quarter of the 20th century and packed movie theaters for months.

After the fact the Star Wars series was novelized. Lucas wrote Episodes IV-VI (the first filmed trilogy) himself. There is nothing in that book that can capture the awe and power of that thundering star cruiser with its screeching laser cannons. Besides, the books don't have the Oscar-winning soundtrack by John Williams (that year he beat out his own soundtrack for Close Encounters of a Third Kind). It would be hard to convince many that Star Wars the novel is better than Star Wars the film.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)