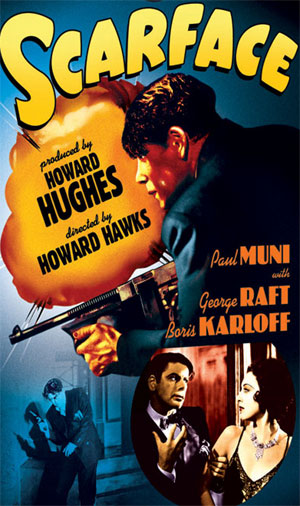

the big three: Little Caeser, Public Enemy, Scarface

Fascination with crime and criminals is not a new thing. In literature you can't get much more villainous than the bloodthirsty, power-hungry title character of Shakespeare's Richard III. In motion pictures there were films about organized crime even before D.W. Griffith's groundbreaking silent movie The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912).

But the genre got its first real impetus from three Prohibition-era films. Mervin Leroy's Little Caesar (1930) propelled Edward G. Robinson to stardom as Rico, who starts as a petty gangster and rises to power in Chicago only to have his criminal empire come crashing down. Modeled after Al Capone, Rico is a rough, tempermental and ultra-violent. Although Robinson's Rico is cast in a dark light, audiences were swept along with the gangster's shifting fortunes much the same that radio listenters and newspaper readers were fascinated with the real-life gangsters (Capone, Dutch Schultz, Johnny Torrio and dozens of others) who provided the alcohol that the 18th amendment had made illegal and who, after all, usually only killed one another and, after all to expand their territories.

In 1931 William Wellman made Public Enemy. As bootlegger Tom Powers, James Cagney rivited audiences with his descent into madness. Starting out relatively mild, by the end of the movie Powers is ultra-violent, brash, loud, and filled with a sense of his immortality. Cagney would carry this quirky, hell-bent personality on to a 1949 film called White Heat (in the famous climactic scene he is surrounded by burning derricks, and shouts "Top of the world, ma!" before he is destroyed). But back to the earlier Public Enemy. This was the first truly stylish gangster film. Wellmen's lighting and camera choices are textured and moody; they draw viewers in and manipulate emotions even more seductively than the soundtrack. Once again, the gangster's life is shown as decadent and self-destructive, but audiences could not turn away from the film's final powerful scene (no, I won't spoil it; you should all go see all three of these movie).

And then Howard Hughes hired Howard Hawks to bring what is arguably the most violent of the classic gangster films to the screen--Scarface (1932). This movie, subtitled Shame of a Nation had Paul Muni playing Toni Camonte (another thinly-disguised version of Al Capone). Featuring the classic tommy-gun toting gangsters now associated with the era of speakeasies and the St. Valentine's Day massacre, Scarface gives us the rise and fall of a murderous, incestuous (yes), thug as he descends into paranoia and madness. The movie was nearly banned for the viciousness of its main character and the piles of bodies that filled the screen.

These three films were so disturbing to some who feared that the carefree, irresponsible, high-living lifestyles of these gangsters was dangerously attractive. And this ushered in the era of The Hays Code--an office that applied rules of censorship for films. By the mid-1930's gangster films had to make gangsters appear pathetic and unattractive. Violence was reduced to a minimum. The Hays Code would actually affect films in all genres for a long time to come.

the loveable rogue

In the 1890's E. W. Hornung, ironically a brother-in-law of Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur Conan Doyle, created A. J. Raffles, a gentleman theif. Based on an actual Cambridge-educated burgler named George Ives, Raffles plays cricket, attends his club in London, is socially well connected. As a master of stealth and disguise, he plans various heists (targeting those who are wealthy enough to afford the loss of a few precious jewels) and is basically wry, witty and charming. He's a criminal, but he's very hard not to like.

There are loveable rogues (such as Robin Hood) in both literature and film. Sometimes we are so invested in the criminals (in movies like Topkapi or the old-or-new Ocean's Eleven movies, that's we have to remind ourselves that these are the criminals we are rooting for. They're just so dashing, clever, and likeable, though.

In film the acme of this sub-genre is Alfred Hitchcock's To Catch a Thief (1955), starring an ultra-suave Cary Grant as cat-burgler John Robie. An American ex-pat living on the French Riviera has given up his criminal ways, but a wave of high-end jewel thefts (and the ensuing insurance claims) prompts Lloyds of London to hire Robie to find the criminal. "It takes a thief to catch a thief." Actually, the cat-burgler storyline with it's twists is secondary in this movie. It's the romance of the location, of Grant and his co-star Grace Kelly, of the sweeping camera shots that make audiences want to follow the plot to its (maybe) surprising conclusion.

where are we now?

Yes, there are certainly displays of monstrous behavior that is fascinating but basically off-putting in works like Thomas Harris's Red Dragon (made into Michael Mann's 1986 film that introduces us to Hannibal "The Cannibal" Lecter--Manhunter (by the way, I agree with the minority that finds Brian Cox's portrayal of Hannibal Lecter far superior to Anthony Hopkins's version).

But things are not always so simple. The television show Dexter, for example, features a serial killer (now a parent of a baby) who is really the hero of the piece. He's a violent and methodical avenger who seeks justice when the legal system or the police fail. A recent billboard advertising the show displays him withs two huge sprays of blood on either side of him in the shape of angel's wings.

Movies like John Singleton's Boyz N the Hood (1991) leave us on the fence. The gangsta lifestyle is not pretty; it's not nice. It is, however, reality in many American cities, and the allure of wealth, power, cars, cribs, drugs--all punctuated by driving hip-hop and rap accompaniment is very seductive to some audiences. The fascination of the horror and the sense of social strictures being overthrown by people who have little way out of poverty brings us back to those 1930's films in a way. Sometimes, in a world where we have Swordfish using technology to bleed off the banks (now a symbol of corporate greed and corruption...it's us Vs. them), rogue cops and criminals joining forces to stop badder bad guys while driving Fast and Furious muscle cars, and Sons of Anarchy re-enacting edgy but understandably human concerns with relationships and money woes, it's hard to know which side to root for.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)