Literature and the Motion Picture

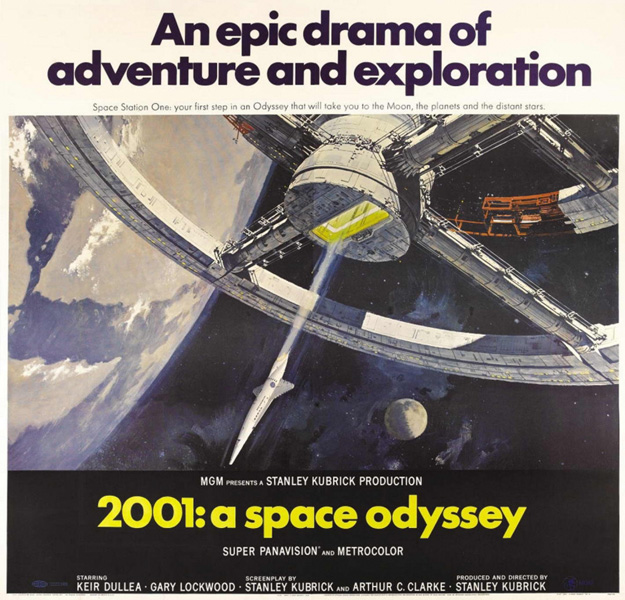

Space is quiet. Space is slow. An unteathered astronaut who moves recklessly outside a space vehicle in near zero-g will fly noiselessly and helplessly out of reach of his capsule. The spacecraft itself may be rocketing through space at many thousands of miles an hour, but distances between planets is so vast, that the journey seems painfully slow. So Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) was a groundbreaking work of science fiction filmmaking. For the first time a major motion picture attempted to really capture the future as it might genuinely appear. Rockets did not whiz around making sharp banked turns (banked against what?); astronauts did not dash along in sleek silvery suits and point rayguns and berserk robots or tentacled monsters. The movie is a ballet of space travel; it's slow and elegant and measured, and it looks possible.

Of course 2001 is now literally in the past, but the idea is still of a future when space stations house travellers bound for research labs on the moon, and where adventurers press on well past Mars.

Even though some of the film technology is now old stuff, and even though the transition through the star gate (not mentioned as such in the movie) feels like a psychedelic trip from an era long gone, the book and the film are particularly relevant to this class. The two works were developed concurrently. Arthur C. Clarke (who wrote the novel) worked with Kubrick and influenced the film's content; meanwhile, Kubrick reported what he was doing on the film and influenced the book's content. Ironically, what they ended up with were two very different products. Clarke's novel (based in part on his 1948 short story "The Sentinel," tells the story using the tools specific to writing; Kubrick's version shows the story using the tools specific to the filmmaking.

The two planned for the release of the movie shortly before the book was published, and the effect was magical. The film was widely viewed by audiences who just didn't get it. I recall sitting in the Hollywood Pantages theater anticipating the much-hyped space epic and was perplexed that the opening quarter hour was about apes, not space. Ethereal choral music emanating from a featureless black monolith seemed somehow responsible for the evolution of this lower order into something human-like, and in a metaphorical cut showing one advancement leading to another, a jawbone turned into a killing tool flung triumphantly skyward is replaced with a spaceship descending. Huh? The two-and-a-half-hour (long for the time) movie moved from one perplexing scene to another. The story is told in four movements (with a rich classical score): "The Dawn of Man" features the evuloution of the primates; "TMA-1" brings Dr. Heywood Flloyd to the moon where he examines an artifact (another black monolith) that has been buried for thousands of years (the monolith sends a signal off toward Jupiter, and this leads to the next movement); "Jupiter Mission" is the long voyage of Discovery One where astronaut Dave Bowman struggles with the onboard HAL (add one alphabet position to each letter, and you get IBM) computer which seems determined to kill all of the astronauts for reasons not made clear until a sequal novel); "Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite" is the strangest of all four parts--Dave hurtles past colorful space-and-landscapes and is installed in a spotless room where he grows from old man to corpse to infant only to float as the transformed, gigantic space fetus looking down curuiously at the earth from above. Huh?

The book soon followed. This was not a novelization (so popular with films nowadays); it was produced at the same time, and, in fact, Clarke's ideas pre-dated Kubrick's by decades. People (I was one of them) gobbled up the book to try to make sense of Kubrick's vision. His work had scope and majesty and power, but parts of the story were out of reach. The book was the monolith that enlightened viewers much the same way that the black slab in the film put the concept "tools" into the minds of the primates. The book mades sense of the sights and sounds. It is in the book where we learn, for example, that the trippy light show Dave shoots past is a stargate, a tesser-like link between worlds; it's also in the book where we learn that the Starchild (the space fetus) is Dave evolved into the infant form of humanity's next next evolution, and the final line of the book (which I won't spoil here) is both thought-provoking and a bit chilling.

So here, at the end of the course, we come back to the beginning with a simple observation: writing explains; film shows. Yes, writers use imagery that evokes mental pictures, but we create the pictures, and the writing puts them in context. Why not explain what HAL's intentions are? Because Dave doesn't know what they are. WE would not know what they were either. We see a black slab. Why would we assume it's an alien technology, in one case a catalyzing device, in another a signalling device? It just looks like a huge black stone. So there we are, alongside Dr. Floyd looking at a "thing." He doesn't know what it is, so why would we? The author of the novel tells the story; he explains rather than just shows.

So just as the shuttle and space station in the movie perform a leisurely ballet to the strains of Johann Strauss's "The Blue Danube Waltz," the book and the movie are carefully choreographed to give us a new view of space and a demonstration of the gestalt when writing and film are paired.

The Science and The Fiction

The field, which Harlen Ellison expanded with his term "speculative fiction" encompasses many things. Science fiction that is strongly grounded in hard science can be found in books such as Fifth Planet by astronomers Fred and Geoffrey Hoyle, and mathematical concepts form the basis for Robert Heinlein's "And he Built a Crooked House" and Madelaine L'Engle's children's classic A Wrinkele in Time. Books like Larry Niven's Lucifer's Hammer attempt to project the consequences of a natural disaster powerful enough to devastate most major world centers, and Harry Harrison's Make Room! Make Room! speculate on a world beset by just about every other sort of disaster (overpopulation, greenhouse effect, pollution, food shortages, etc.).

The key word in much of this material is "speculative." One role of the science-fiction writer/filmmaker is to speculate, based on the past and the present, what might happen or what might have happened differently.

In the former category, here is the sort of question that might be posed: "Based on how wars have been fought and are currently fought, how might wars be fought in the future?" Possible answers appear in Joe Haldeman's Forever War, Robert Heinlein's Starship Troopers, Orson Scott Card's Ender's Game. In the latter category this is the kind of question someone might ask: "What would the world be like if the Allies had not won the second world war?" A couple of works that proceed from this premise are Norman Spinrad's Iron Dream and Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle.

Film and literature both are crowded with dystopian visions, from George Orwell's 1984 (made twice into films), Aldous Huxley's Brave New World and Lois Lowry's The Giver, to films such as Fritz Lang's (silent) Metropolis, George Lucas's THX-1138, Terry Gilliam's Brazil and Geoff Murphy's The Quiet Earth. Here the "what if" questions center around post-apocalyptic civilizations in the wake of nuclear and/or natural disaster, hamstrung societies in the grip of repressive political structures, mega corporations controlling the lives of drone-like-and-disposable workers, media-drenched populations manipulated like puppets.

Science fiction is often action packed and filled with techno-wonders, but it's also among the most thought-provoking literature/film because of its speculative nature. Ridley Scott's Blade Runner (based on the Philip K. Dick novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?), for example, wrestles with the concept of "What is human?" The answer seems simple enough, but when a replicant/android/artificial intellegence can so authentically-mimic human biology/action/thinking, at what point does it become indistinguishable from humans? This same notion is explored in Richard Mathesson's I am Legend, Alex Proya's version of Isaac Asimov's I, Robot and Steven Spielberg's A.I. (based on Brian Aldiss's "Super Toys Last All Summer Long"). If these are not heady enough, we can look back to the lecture on "What is real?" Most of the film examples were science/speculative fiction works.

Yes, some of it is bug-eyed monsters and alien invasions, but much of this genre is about possibilities, imagination, ideas.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)