reading and seeing as a child...as an adult

is Corbally stealing from himself again?

Those of you who've taken my Children's Literature course will recognize the opening of this lecture. Heck, if it works in two spots, why waste it? And don't fret, it starts the same, but it will take us in a new direction.

First read Little Red Cap by the Brothers Grimm and Little Red Riding Hood by Charles Perrault (both are in our Online Anthology; click the links to get to the stories). Next read what a well-paid analyst (actually a child psychologist and literary critic) Bruno Bettleheim has to say about the two stories in this excerpt from The Uses of Enchantment

Little Red Riding Hood is a female with lax morals? Her counterpart Little Red Cap has an Oedipal (actually an Elektra) complex? The wolf and hunter represent father as seducer and protector?

Bruno Bettleheim's The Uses of Enchantment , a Freudian interpretation of folk and fairy tales, seems a bit far-fetched. We can't imagine that the orginaters of these tales would have dreamed of such stuff or even if they did that a child (or most adults) would come to any of these conclusions.

Perhaps that is not what Bettleheim is saying. He clearly favors Little Red Cap over Little Red Riding Hood because Red Cap's character is challenged, experiences difficulty, receives help, and eventually learns from her experience. Little Red Riding Hood simply disobeys and is destroyed because she failed to listen to Mommy and Daddy enough.

Little Red Cap learns, and the child listener/reader realizes that parents make rules for reasons; mistakes happen and (usually) are not fatal; kids can learn from their mistakes. The pattern is hopeful. The ending of the story, where "Little Red Riding Hood thought to herself, as long as I live, I will never by myself leave the path, to run into the wood, when my mother has forbidden me to do so," also suggests that children do grow and become more independent. Red Cap is not thinking that she will never leave the path again, she will just wait until it's not forbidden, when she is ready and is given more opportunity to make her own decisions.

Little Red Riding Hood is, in Bettleheim's view, just a cautionary tale. Like Frederich Hoffman's Struwelpeter and Roald Dahl's Charlie and the Chocolate Factory the story is a warning to kids saying, "If you mis-behave or fail to do EXACTLY what grown-ups tell you, you will be punished, perhaps even killed." A child might grow fearful but not more independent and responsible reading Perrault's story.

OK, that seems reasonable, but what about all of the psychological analysis that ties these stories to sexual development? Even though Bettleheim supplies his chain of reasoning, it seems a little silly to look at a children's story so deeply. Certainly no child will read "Little Red Cap" and say, "Hmmmm ... Red Cap is competing with her father's love and needs to kill off the more experienced competition, (figuratively) her mother."

But Bettleheim never says that a child WILL articulate this sophisticated and not-very-child-like notion. He DOES, however, suggest and fairly clearly demonstrate that the story does follow that pattern and COULD be interpreted psychologically, even if that was not the original storyteller's intent.

When we analyze fiction (film, stories, plays, etc.) we are trying to discover what ideas and issues that fiction calls up, suggests. It's rarely stated directly, but the implications of character choices, the directions the plot takes those characters, the surrounding setting and symbols--all of these can make a simple story remind us of our own lives and our own observations about the world. No, we are not little girls carrying baskets and wearing red capes while we walk with our baskets through the woods, but we've all been young; we've all had journeys (some physical, some emotional); we've all had to overcome obstacles.

so what, exactly, does this have to do with us,

and why are we looking at little-kid stories?

Since I often like to do things in reverse, I'll answer the second question first. We are starting with little-kid stories because they are rudimentary; they have all of the basic elements of storytelling, and both fiction and film are, essentially, forms of storytelling. One writer of children's book illustrations called the surface images "cobwebs to catch flies," and most folks I know love the surface of things, the stories, the action, plot, simple character twists; in films we add to that eye and ear candy, and there's a good chance we'll enjoy the experience.

But the many of the most memorable works engage us in several ways. Watching the streets of Paris fold up Escher-like in Christopher Nolan's Inception is pretty darned amazing. But what folks mainly talked about around the water cooler was the spinning top at the end of the movie (note: please do not spoil the end of this movie for anyone).

Just consider that there is, perhaps, room for several levels of interpretation, even with the earliest tales we've grown up half remembering. The stories are charming, whimsical, fantastic. They also seem to teach simple lessons about listening to parents, avoiding strangers, working as a team. Beyond this they are open to psychological interpretation. They are often rich with symbols and suggestions; they work in large part because they have patterns that correspond to different human experiences. No, I've never seen a giant's castle literally perched on clouds; in fact, my physics background protests at such nonsense. But I certainlly do know that people have misconceptions about people who are different; sometimes crimes are justified (rightly or wrongly is not what we are concerned about; we're trying to be objective observers of ideas and experiences) by needs and fears and greed. "Jack and the Beanstalk" works because the giant is a cannibal; he's a threat (perhaps like a dictator or some cruel force of nature); however, in Jack we see someone (an entrepreneur?) who exploits a situation to his advantage first out of need, eventually out of the simple thrill of succeeding at someone else's expense. We are rooting for a thief (like Cary Grant in Hitchock's To Catch a Thief in large part because he's bringing down the equivalent of big banking, insurance, greedy-outsourcing mega-corporations.

Did the original authors (who are unknown) of "Jack and the Beanstalk" intend to write about corporate greed? Hardly. There were no corporations at the time. But we can still see these patterns in the story; what makes them work again and again is we can apply patterns and suggestions that we see in the stories to our own experiences, and the experiences are broad, human experiences, not just local ones (which is, perhaps, why there are "Cinderella" and "Red Riding Hood" tales that were independently created in hundreds of different cultures). The more logical interpretations a story can support, the richer the story (Note: here logical means that the conclusions can be supported by what is happening in the text of the stories).

And we are going to take our cues from that. Yes, stories have surfaces, and we like them or not (based on personal tastes), but we are more concerned with what ideas and issues are suggested by the readings and movies.

and films have re-interpreted these stories again and again

Consider Garry Marshall's movie Pretty Woman. Like it or not, this showcase for Julia Roberts and Richard Gere was a tremendous success. Why? Because it was the "Cinderella" story made relevant to audiences of 1990. Princes are rare nowadays, but rich, ruthless businessmen are the stuff of our daily news. In a nation where we pretend not to have distinct classes, it's hard to find the combination of lower-caste and incredibly beautiful (which is what we have in the folk tale), so the writers give us a lovely, high-end prostitute. The two are separated not as royalty and commoner but by degrees of wealth and kinds of occupation (which is, if one really thinks about it, a way many Americans view social divisions.

Sometimes we see the patterns ourselves; sometimes we see them revealed in other works. For example, Bettleheim's work encourages us to see some (not all) patterns in a number of folk/fairy tales. He is essentially a Freudian critic, so the literary interpretations are often laced with symbol systems found in psychoanalysis. To reinforce this interpretation, while adding to it, author Angela Carter wrote a collection of stories gathered in her book The Bloody Chamber. A few of those, including "The Company of Wolves," inspired Neil Jordan to make. In all of these the sexual symbolism of the bright red cloak and the transformation of men into beasts (werewolves) when encountering a young, beautiful woman are not lost.

Are these all children's stories? Who can say? Children will not understand situations they are not ready to understand (this is one of the points made at the end of "Little Red Riding Hood" where we are told that "Little Red Riding Hood thought to herself, as long as I live, I will never by myself leave the path, to run into the wood, when my mother has forbidden me to do so." Until she understands the implications of making her own choices (straying from the path dictated by her parents) and is old enough to exercise some independence, she will still follow mom's rules. That does sound like the sort of message parents tell their children. The real difference is in the "why"--the young girl can fall prey to the wolf/man who wants to gobble her up, but that is not always the case. In Jordan's movie young Rosalee (Red), who is now old enough to be interested in boys, asks her mother, "Does dad hurt you [when you are making love]?" (it's a small village with small houses; this pre-dates soundproofed bedrooms).

Then Rosalee says that her grandmother says that there is a beast (wolf) inside men, and the mother replies, "If there is a beast in men, it is matched by women." Rosalee does not understand what her mother is saying, but we see the parent is strong and in control; the mother is mature and experienced enough to no longer have to listen to the rules of grandmother.

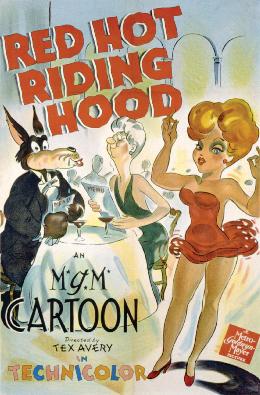

Once again you might ask if the original storytellers intended this sexual teen-becomes-adult interpretation? Who knows? What we really care about here is that the interpretation fits; it makes sense given the patterns we see in the story. The later versions (written or filmed) often give us new ideas about what levels of meaning we can apply to the original stories. And it doesn't always take much sophistication to arrive at these interpretations. For example, Tex Avery made an MGM cartoon version in 1943 with the wolf as a nightclub-hopping playboy and Red as a red-hot jive singer.

Alas, I did have an embedded clip here, but Warner Brothers (who now hold the copyright) blocked the content. However, if you go to YouTube and search out Tex Avery Wolf, you will probably find several versions of it.

Hmm...this sort of thing might lead to a very interesting paper about stereotyping, values (smoking and drinking are prominent in this vintage cartoon) and images of men and women in WWII (or other era) films.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)