more real than real

The nature of reality, of what is human, of what can be known and how questionable human observation might be is a very old subject. First read over the snippet from Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking Glass in the sidebar on the right.

If you have seen Inception or Dark City or The Truman Show or Total Recall, you might think that Carroll was the inspiration of these dream fantasies (the earlier Alice's Adventures in Wonderland is also a dream).

Like Samuel Johnson, who was so peeved at the empirical philosopher Bishop Berkeley's theory of the non-existence of matter that he kicked a stone and said, "I refute it [the theory] thus!" Alice gamely challenges Tweedledum and Tweedledee. She is sure she is real and not just a figment of the Red King's dreams. However, she may not be all that sure. Playing it safe, she hushes the twins when they are making so much noise that she fears they may wake the king up.

"life, what is it but a dream?" final line of Through the Looking Glass

Before we give too much credit to Lewis Carroll, this idea is far older than the Alice novels. Carroll ends Through the Looking Glass with an acrostic poem (reading the first letter of each line from the top down we see the name Alice Pleasance Liddell is spelled out) with a nod to a far older nursery rhyme:

Row, row, row your boatThis is the sort of throwaway verse that kids have been singing for hundreds of years, but it's packed with metaphysical conundrums. Is life just a dream? Are we, like Willy Wonka, living in a world of pure imagination? Are we even certain that our sciences (studies of means of measuring the universe objectively) really reasonable tools for mapping the real world?

Gently down the stream.

Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily

Life is but a dream.

Consider this parable that originated in India many hundreds of years ago and which has been re-told as a Chinese folk tale, a 19th-century English poem, and so on:

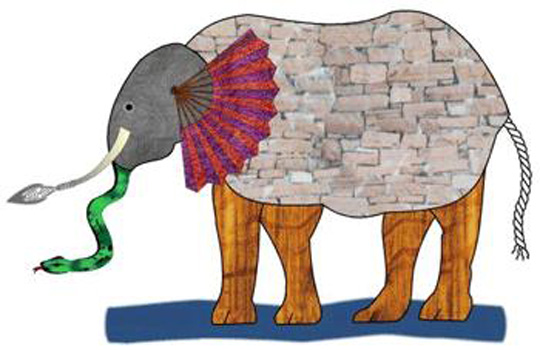

The Blind Men and an Elephant Three blind men happen upon an elephant sleeping. Having never experienced an elephant before the three eagerly spread out and began to touch different parts of the elephant. One wrapped his arms around the sleeping elephant's front leg; the second grabbed a hold of one of the elephant's ears, while the third took hold of the elephant's trunk. Sensing that the elephant was beginning to wake the three quickly ran off. When they stopped to rest the three men began to talk about the elephant and what the elephant looked like.

The first man said "an elephant is round like a tree trunk with no branches."

The second man said "no no, an elephant is flat and leathery like a drum skin."

Then the third man said" no no no, you are both wrong! An elephant is long and thick and strong like a snake."

Different versions have different numbers of blind men touching different elephant parts, but the upshot is always the same. Each observer (with limited perception) assumes that one small part of the elephant is the whole elephant.

English teachers love trotting out "the bard" (Shakespeare) whenever possible, and here are just a couple of bits he has to contribute:

All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players:

(As You Like It II, vii)

Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

(Macbeth V,v)

If you find youself enjoying this sort of thing, you might also wan to read Edwin A. Abbott's 1884 Flatland: a Romance in Many Dimensions.

But don't feel compelled to read every Philip K. Dick or Koontz and King novel, all of the surrealist and existentialist playwrights, the stories of Akutagawa and Cortazar; the point is that this concern about the nature of reality is not new to fiction. Certainly Plato's dialogue (which is the main text for this week's discussion) shows us that the idea has been kicking around in literature for over two-thousand years.

One wonders why.

Plato and the Wachowski brothers

"I know what you're thinking, 'cause right now I'm thinking the same thing. Actually, I've been thinking it ever since I got here: Why oh why didn't I take the BLUE pill?" (Cypher speaking to Neo in The Matrix)

Plato's Republic, from which we get "The Parable of the Cave," was written about 360 BCE. It's not the earliest Western writing on the nature of "what is real" and "what can we know," but it's certainly one of the most famous surviving texts on the subject. In the parable humans are likened to creatures chained to chairs facing the wall of a dark cave. All we can perceive are shadows cast on that wall from images that are drawn in front of flickering candles. Like flashlight shadows of dogs made on boy scout and girl scout tent walls, the fingers of our hands represent ears, nose, mouth, but the shadow is hardly a real dog. It's a representation (like Magritte's pipe painting mentioned in Lecture 1), and it's a very rough (though fun) representation.

Perhaps we are not meant to see the puppets in front of the candle; perhaps we don't have the ability to (our senses are, after all, quite limited; we can't hear sounds that dogs can; we can't see infra-red or ultra-violet). This is disturbing whatever the reason because people like to imagine they have control of their universe(s); people like to understand things.

Plato gives us another sock in the jaw, though. Even if we were to turn and see the images in front of the candle, we would still be seing crude representations in a dimly-lit, claustrophobic cave. The really real forms (not unlike Carl Jung's archetypes) are in the light, outside the cave altogether. Humans have sought this light, this illumination, this transcendence from what Philip K. Dick was to call "the iron prison of Rome" as long as there have been seekers of truth, spiritual leaders, philosophers, imaginative thinkers.

The idea itself is compelling, but it's hardly literature; it's not particularly filmic. To have someone chat about what is or is not real might get us thinking, but film and literature revolve around story. The point here is that stories can and do often spring out of ideas and issues. The implications can be far-ranging and unexpected. Taking the idea that life is a dream and turning it into a layered thriller gave us the blockbuster Inception. Adding the spice of conspiracy theory, runaway technology, xenophobia, suspicion about politics and popular culture gave us the Wachowski brothers' phenomenon The Matrix.

The basic premise is much the same as Plato's parable: what we think is real is not really real. In The Matrix this idea/premise is just the cornerstone of an action-packed, visually-thrilling suspense/sci-fi/adventure about the battle between humans and an alien computer-hive-mind (The Matrix). The aliens have enslaved humanity (here the idea gets a bit silly; you'd think the aliens could find better "batteries" than human bodies, but its a minor point, and most viewers don't give up there). What people believe is real--cities, jobs, daily lives, relationships--is all artificially-induced imagery and memory fed directly into the brains of pod-bound people. A small band of rebels has awakened to the truth, and they seek the help of a chosen one, Neo (new). First Morpheus (sleep/dream) needs to convince Neo that there is a plot, a conspiracy, that what appears to be real is actually illulsion. Like most heroes Neo has a choice: he can take the red pill and raise his consciousness and enter the wider world (does this remind you of Luke Skywalker discovering "the force" in Star Wars?), or he can take the blue pill and keep things as they are, simple. He takes the red pill, and the adventure and battle begins. And the slo-mo battle scenes are spectacular.

So the idea, the Plato bits, become the catalyst for the story, but as literature/film, it's the story in service of the idea that makes readers and audiences come back.

Stories also try to engage audiences on a human level by making those ideas/themes relevant. Plato's work is not just a lofty exercise in academics; he introduces political implications of being able to exploit limited perception. The Matrix brings these human implications into the 20th (now 21st) century. Consider the following topics (and this is just a partial list) suggested by the movie that could be discussed at some length:

The Matrix is a technological construct that manipulates information to control humans. In the United States (and elsewhere) the media is controlled by a very small, powerful, select group of individuals. Often what news broadcasters focus on is deceptive, slanted, diversionary (a dozen years ago the world was ripe with conflicts and issues, but the most reported items on television were long car chases around the Los Angeles area. Are stories about celebrities going into re-hab ways of distracting people from troop mobilization? tax increases? erosion of Constitutional protection?

The Matrix is a mega-machine/computer which is powered by humans who, in turn, are mere electrical parts of that larger machine. In Fritz Lang's 1927 classic Metropolis humans are separated into class (the sky-city dwellers (the powerful, rich bourgoisie?) and the subterranean workers (the grim, toiling prolotariat?); in one scene a worker becomes a part (a human switch) of a killing juggernaut os a machine. Many authors and artists have explored this idea that in the modern world individual human dignity and worth is lost as we are part of a huge conglomerate, corporate monster, bureaucratic nightmare.

Cypher, the traitor in the story, sells out the rebels to the agents of The Matrix. In exchange he is offered the choice to be disconnected from The Matrix or to be plugged back in, and he chooses the "blue pill" option--to be put back into a sleep where he will be fed false images of reality. Although he knows he is living in illusion, although the steak he is eating is not really steak and the wine he is drinking is not really wine, he still tastes the deliciousness of each. Like people who know that facebook is not the same as having physical friends and that reality television is not really real, it's comforting and satisfying and familiar and easy. He'd rather live in blissful ignorance and fantasy. Is Cypher's position really the more attractive one? the one that most people would adopt because it requires the least effort?

Neo takes the red pill and awakens to real reality, or does he? Could he, like the characters who enter dreams within dreams within dreams in Christopher Nolan's Inception, just be in a different un-reality? How could he (we?) ever know? Likewise, in Plato's dialogue could the light outside the cave be just another shadowy representation of reality rather than real reality?

And here's an add-on to that last question: even if it's not what someone would consider reality, doesn't the very fact that it's being experienced by a person make it really real for that person at that time? The Matrix experience is real experience for those in The Matrix, no?

And so the idea begats the story (many stories and many movies). In turn, the story causes readers and viewers to think about the idea and its various implications. I mentioned earlier that the incredible buzz surrounding Inception was, in part, about the scene of the street folding Escher-like up on itself, but much more chat was about the spinning top. Again, do not spoil the ending of this movie; those of you who've seen it know what I'm referring to; the rest of you, well, go see it :)

This scene from Inception is a nifty way to end this lecture; embedding was disabled, but the links will take you to two YouTube clips: explaining the dream landscape followed by building the dream landscape :)

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)