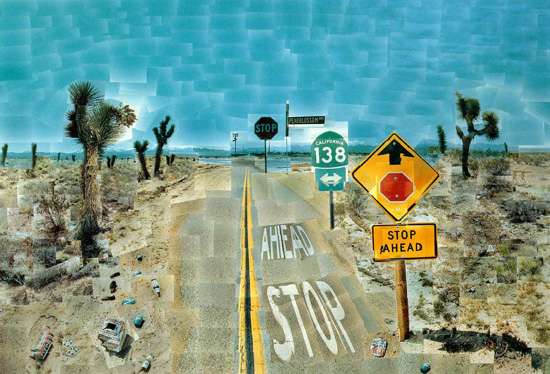

"The long and winding road, that leads..." The Beatles

Road trips are the basis of songs, stories, movies, works of art, and they have been for thousands of years. Odysseus making his way back to Ithaca after the Greek victory at Troy is an eleven-year trip with adventures, lust, human weakness, human ingenuity. J.R.R. Tolkein's The Lord of the Rings trilogy is a long journey to destroy a ring of power that threatens to corrupt the ring bearer, as any sort of power has the potential to corrupt a person. George Miller's Road Warrior is a futuristic knight's quest to preserve human civilization and dignity in a post-apocalyptic world where hardship and scarcity have turned many people to their baser animal selves, and Chevy Chase in

The term "road picture" became popular with a string of seven Bob Hope and Bing Crosby movies that began with The Road to Singapore (1940) and ended with The Road to Hong Kong (1962). The movies, which took the boys to exotic locales, were showcases for adventures, gags, songs, Hollywood satire. The plots were thin, and the focus was on entertainment--not a bad thing.

But stories about journeys are ancient. The topic works so well because, as writers such as Joseph Campbell have pointed out, life is a sort of journey. We move through space and time; we have experiences (some adventurious, some amusing, some tragic, some ecstatic), and we imagine/hope that through experience we will grow, learn, develop, reach goals and accomplish things. A four-year (or so) journey through college is not the same as the journey of a great hero who faces dragons and wizards and temptresses. But college, on a human level, does have it's obstacles and puzzles and temptations. The story is a larger-than-life (exaggerated, embellished) journey that suggests the more mundane journey through college or around the workplace or into a relationship. The story (topic) suggests ideas (themes) about human nature.

Everyman

Everyman (author unknown) is a fifteenth-century morality play--an allegory (it is clearly symbolic; one thing represents something else) and which attempts to teach a lesson. The name Everyman itself is a a straightforward symbol: the main character represents every person. A character named Death, represents, well, death. The journey along the road of life towards death is another easily-decrypted symbol: every person moves through his/her life and will eventually die.

If this play seems awfully simple and preachy, that's because it is. Literature exists in context, and the sophistication that allows a 21st-century reader to wrestle with Cormac McCarthy's thematically-challenging The Road is not the same audience for which Everyman was written. Theatre majors probably know that much of early theatre was religious in nature (the Greek tragedies were performed at the great festivals that honored the gods and goddesses, for example). Most people in England in the fifteenth century could not read, did not have leisure time to philosophize and debate fine points of theology. Morality plays, sometimes performed on huge carts--mobile stages--in front of the large churches, were ways the Church (Roman Catholic at the time) could teach ideas about scripture, moral choices, doctrine to the masses. The stories were obvious, direct, didactic, but in a world where most people died quite young and labored in fields sixteen-hour days, six days a week, the plays/stories were also highly entertaining; they provided a welcome break from hardship and monotony.

The story centers around a journey. God, angry at how humans have become sinful, calls to Death and asks him to seek out people to be judged. Death approaches Everyman who does not want to take the journey to be judged before death, and Everyman asks Death if he can bring along some friends for the journey. Everyman approaches Fellowship and Family and Meterial Goods, and all come up with excuses why they can't accompany Everyman on the journey. Everyman meets up with characters named Good Deeds and Knowledge, Beauty, and so on, and they are able to help him along the way. Everyman is required to go through the rituals of confession, penance, etc., and eventually all but Good Deeds leave Everyman.

In case the theme (idea/message) of the play is still too difficult for the audience, there is an epilogue that spells it out.

but we're not in the fifteenth century any more

Ideas suggested by literature, films, arts, music are often much subtler nowadays, but there's still a huge range.

Danny Leiner's Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle does satirize popular culture, but it does not require much thought. Albert and Allen Hughes's The Book of Eli has much of the same pop culture satire and a message that is not too far removed from Everyman, but it also tickles some issues as we see what human nature unchecked can be like and how human carelessness can lead to global disaster. Then there is Cormac McCarthy's The Road (you could look at John Hillcoat's film version, of course). This work has much of the bitter satire of nearly all post-apocalyptic works, but it demands much more thought than L.Q. Jones's action-and-humor-driven A Boy and His Dog. After reading The Road several suggestions come to mind: this is a literal struggle against nature, humanity, despair in a world torn apart by nuclear disaster; it's the story of a parent's struggle to preserve his child, to pass on survival (natural, urban, social) skills to a successive generation; it's an allegory about the grim determination to "carry the fire" (keeping the spark of life glowing) even though life, the universe, and everything seems burdonsome, self-perpetuating, pointless; it's a religious allegory peppered with symbols and allusions.

There are loads of variations; here are a few:

- the quest

Very few of us (short of Indiana Jones) will spend much time actively pursuing the holy grail as the grail knights did in Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur; likewise, we will probably not seek the Ark of the Covenant or the Golden Fleece. In The Epic of Gilgamesh the title character, after the death of his beloved Enkidu, seeks an emerald granting life. In the Disney-animated The Black Cauldron young Tyran and his unlikely companions must find a powerful magical item before the Evil Horned King can use it to enslave the world. Harry Potter and Voldemort are in a race to find (or hide) horcruxes and the three elements of the Deathly Hollows. The Ring Bearer (in Tolkein's trilogy) is on a quest to destroy the one ring of power. The quest items may be symbolic (in the latter case, for example, the ring represents the corrupting nature of power), but their real function is to get the story moving, to get the hero on the road.

These stories and movies work not because most readers/viewers will experience vivid, fantastical adventures but because every day is a mini human adventure. We turn the house over looking for a the lost remote; we pore over pages of Yelp trying to assemble the perfect first date to build a new relationship; we seek the aid of the GPS voice to help us avoid a back-up on the 405 freeway, or we just push our carts up and down the aisles of Food 4 Less to find something that "sounds good" for dinner. The goals in fiction are magnified; the heroes walk through walls of flame rather than try to maneuver around the guy who's left his cart blocking the canned spaghetti , but the lofty goals of fiction parallel our more mundane, real-life goals.

- water journeys

Water often symbolizes change/transformation, and many journeys take place on the sea or along rivers. Odysseus seeks home after years of war in a foreign land, but before he can reach the arms of his wife Penelope, he is sent on a life-altering eleven-year series of adventures around the Mediterranean. Huckleberry Finn and Jim's rafting on the Mississippi is a literal escape from the danger facing the freed slave; it also represent Huck's release from the prejudices that so-called civilized folks on the shores preach; it is a symbol of his free moral sensibility in a world that is often bound by illogical, inhumane, narrow-minded rules. The river in Joseph Conrad's "Heart of Darkness" and it's Viet Nam era remake in Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse now represent the descent into the subconscious, the dark interiors of the human psyche. As Willard, in the movie, goes further up the river towards Colonel Kurtz, whose methods have become "unsound," he experiences how war makes nonsense of so-called normal, civilized responses. When Kurtz asserts that he has seen the "genius" of "the horror, the horror," he is showing that to truly engage in war is to wallow in horrors and abominations; anything else is just pretense.

It's worth noting here that many stories fit into multiple categories. For example, Hans Christian Andersen's "The Little Mermaid" is a story about metamorphosis, and the transitional elements are water (where the mermaid is born), earth (where she operates after her transformation), and air (for the spirit she wishes to become); it is also a quest story and a spiritual journey (she is a beast in search of an eternal soul). Likewise, Herman Hesse's Siddhartha is about the protagonist's journey to find enlightenment, and he experiences a great transformation after immersion in the river.

- journeys to uncover identity

In many stories the main character is trying to discover personal identity. Alfred Hitchcock's Spellbound, Christopher Nolan's Memento, Peter Segal's 50 First Dates, Jon Favreau's Cowboys & Aliens--these all deal with characters with lost or erratic memories. They are trying to discover who they are. In many cases the discovery is not triumphal (and I surely will not spoil the ending of Herk Harvey's 1962 Carnival of Souls or Anne Francis's discovery of who she is at in the "After Hourse" episode of season 1 of The Twilight Zone). The search may be an attempt to uncover family history, a father or mother. Oedipus, in the play by Sophocles, discovers, too late, that he's unwittingly killed his father and married his mother. Luke Skywalker walks the skies of the original Star Wars trilogy eventually to discover his true father (I won't spoil it for those who've not seen the movies).

A variation of this is the character's journey to discover a wider context, a group identity or a national identity. These works, often a blend of history and fiction, reveal the spirit of a place and time and experience. To get a sense of the hardship and divisiveness in much of America in the 1930's/1940's, for example, you might want to watch John Ford's The Grapes of Wrath (or read the novel by John Steinbeck), Preston Sturges's Sullivan's Travels, and maybe even the Coen Brothers's 'O Brother Where Art Thou?. Jack Kerouac's novel On the Road (1957) shows the angst of the Beat Generation much as the enigmatic novel Dhalgren, by Samuel Delaney, symbolizes the radical social changes of the U.S. in the 1970's.

- spiritual journeys

Several stories lend themselves to explorations of our interior journeys--Dante's journey through Hell, Purgatory, Heaven, in his Divine Comedy is his attempt to find the path he must follow to live a moral life; in Hermann Hesse's Siddhartha the title character leaves the material comforts of home in an attempt to discover enlightenment. Even Dave Bowman's tranformation from human to Starchild in 2001: A Space Odyssey (both the novel and the film) is about growth and transcendence, a possible evolution of human consciousness and capability.

In the end, Everyman and most other journey stories before and after it suggest some element of our own journeys through life. Sometimes we have physical journeys (a trip to Europe) where we experience new wonders. But we can also map our less geographical roads--we have career paths and relationship goals, and we attempt to find the right path to live our lives as we quest to discover meaning in a confusing, changing world. We may not travel with Merlin and Medusa and Appolonius of Tyana, Pan, The Abominable Snowman and the Giant Serpant in George Pal's The 7 Faces of Dr. Lao (based on the Charles Finney novel), but our more-pedestrain walks along the road of life is still about discovering the mysteries and marvels along the way:

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)