the code revisited...

One of my favorite movies when I was growing up was John Sturges's The Magnificent Seven (1960). Not only was the cast stellar (Yul Brynner, Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson, Eli Wallach, Robert Vaughn, James Coburn and the like), the story was tightly crafted, one of those movies that requires a group of strong (often quirky) individuals to form a temporary alliance to accomplish some grand-but-nearly-impossible task (the formula for movies ranging from The Dirty Dozen to Star Wars.

It wasn't until I was nearly in college that I discovered the film was actually a re-maike of an amazing Japanese film, Akiria Kurosawa's Shichinin no Samurai (Seven Samurai, 1954). Sporting an equally-steller cast headed by Takashi Shimura and featuring a young Toshiro Mifune (who would eventually become synonymous with samurai to western audiences and become the archetype for the spaghetti westerns in the 1960's). And this is not the only time that a western was a re-make of an eastern.

Westerners have a lot of notions about other cultures; one has to do with the rigid traditionalism of Asian cultures. Ironically, many of thse same westerners fail to see a rigid traditionalism in the characters of popular westerns and detective films.

The exact nature of the code is different; samurai conduct is traditionally credited with shaping the code of bushido (the path of the warrior/knight). The samurai was charged with having simple wants, being fiercely loyal and honorable, mastering martial arts (both hand-to-hand and with weapons), discipline and self-sacrifice. Many have noted the code is very much like the chivalric code associated with knights in the western part of the world. Generally working for a shogun, the samurai class served as soldiers in times of war and police in times of peace. And although there are hundreds of Japanese films (and one of the longest-ever-running daytime dramas in any country) about the samurai, it's actually a splinter group that is most like the American western hero--the ronin.

Loyal to the death, the samurai were supposed to commit ritual suicide (seppuku) following the death or disgrace/disfavor of his lord/shogun. Many did just that. The samurai who did not were "masterless" wanderers, soldiers of fortune or just drifters, who were raised on the code but were considered shamed (and were, therefore, often shunned) for their failure to follow through with a manly death. Without the protection (and regular employment) of a shogun, they were often given the dirty jobs, and here they have a lot in common with the western hero, such as Gary Cooper as marshall Will Kane in the movie High Noon, where a cowardly town leaves Kane, now just a peaceful working man, to face a gang of criminals he'd sent to prison who are now arriving on the noon train to gun him down; his first inclination is to leave with his pacifist/Quaker wife (played by Grace Kelly), but he is willing to sacrifice himself to protect the townsfolk who refuse to back him up.

Seven Samurai features six ronin who work for virtually no pay to help a town of farmers who, in turn, resent and show disrespect to them. The feeble farmers will employ the fighters for the amount of time they need them to drive off an army of thieves who routinely terrorize the farm village, but they will not welcome the protectors to interact with the locals. Typical of so many films that followed, the small force faces long odds for little reward. But they adopt a "Oh, what the heck; why not" attitude. Today is as good a day to die as any, and, after all, they have no other pressing appointments, so they band together and set up their surely-doomed plans to save the village.

Not all ronin formed such improbable alliances as the Seven Samurai. In fact, most of these films showcased individuals surviving with battle prowess and cunning, and many were not wholly heroic. Toshiro Mifune played this solo role most notably in two more Akira Kurosawa films: Yojimbo (Yojinbo, 1961) and its sequal Sanjuro (Tsubaki Sanjuro, 1962). As a quirky, twitchy, scruffy ronin Mifune's Yojimbo plods around the screen lazily. Oh, when he needs to unsheath his sword and make short work of half a dozen attackers, he is a blur of balletic grace and speed. But he often seems too tired to move far from a bowl of rice or a cup of sake. His martial skills are amazing, yes, but his real talent is craftiness. He cozies up to two different warring gang bosses and manages to play one against the other in an attempt to free the town being terrorized by both groups. What this lone samurai has in common with the seven samurai is his outsider status and his championing of the underdog. As with tales of chivalric knights, often young couples, women, children, weak-but-honest villagers, wise old men are being protected from strong, ruthless, criminal predators. Unlike those knights, who often called upon spiritual powers and/or fought like clanking tanks, the keenest weapon of the ronin was his ingenuity (with a very swift sword to back this up).

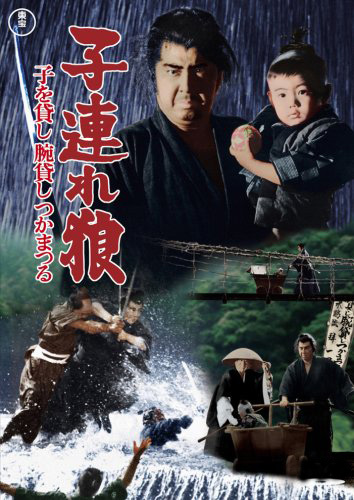

Some of these tales feature near-demonic ronin. Lone Wolf: Sword of Vengeance (the first of the baby-cart assassin series, 1972) starred Tomisaburo Wakayama as the shogun's official executioner who is framed for disloyalty and asked to take his own life as a matter of honor. He nearly does, but when he sees his wife has been murdered, he takes on a haunted, single-minded stare that will carry him thorough several films with titles such as Baby Cart at the River Styx, Baby Cart in Hades, Baby Cart in the Land of Demons. The baby cart is a rough, wooden contraption (sometimes sporting James-Bond-esque gadgets) that carries his infant-eventually-toddler son Daigoro. The thirst for vengeance is so strong that Oggami Itto (the executioner) gives his crawling, infant son a choice: if the baby crawls to a shiny ball, the father will execute him and send him to live in the afterworld with his mother, but if the baby reaches for the samurai sword, he will be the Cub to Itto's Lone Wolf and accompany him on the road of death and destruction. He chooses the sword, and the bloodbath that follows is intense. These films are typically much more graphic than westerns of the same time period (that would all change with Sam Pekinpah's The Wild Bunch, called by many "the blood ballet"). Japanese audiences were not so squeamish as American audiences of the 1950's-80's.

"everybody was kung fu fighting"

Carl Douglas, 1974

Mainland China, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, even the United States were deluged with martial-arts films in the 1970's. Bruce Lee is the standout name (even though he made only a handful of movies and appeared briefly on the Batman and Green Hornet T.V. shows). Many find Enter the Dragon (1973) the landmark martial arts film, but the line from there to Jackie Chan as the Drunken Master (1978), Ralph Maccio as The Karate Kid, Ang Lee's mythic Croching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), all the way up to Kung Fu Panda (I and II) is packed with action stars from around the globe. Not simply a Japanese phenomenon, the martial-arts sub-genre has many faces (The Matrix is often considered part of this class, for example), but most follow the same underdog/outsider uses both brain and brawn alongside near-magical fighting prowess, to overcome improbable odds. The formula and the code have appeared in some other unusual areas.

the spaghetti western

Certainly movies from Italy and Spain are not technically easterns (even though Europe is, arguably, east of the United States), but this incredible viable sub-genre of the western was also influenced by a ronin.

In 1964 Italian filmmaker Sergio Leone went to Spain to film a young Clint Eastwood as the enigmatic man with no name in A Fistful of Dollars (Per un pugno di dollari). The first of three films (For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad, the Ugly round out the trilogy) this low budget western changed the direction of the wester and the fortune of Clint Eastwood (these movies catapulted him to stardom; the Dirty Harry films, which we will visit in another lecture, launched him to the top of Hollywood's bankable stars list).

If the plot sounds familiar--a mysterious drifter enters a small town torn between two warring groups, the Baxters and the Rojos; he uses cunning to pit one gang against the other while profiting from both--it's because it is. This is Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo remade for the west. The ronin prototype with his ability to survive impossible odds, deadly skill with weapons, scrappy craftiness was perfect for this new western featuring an almost existentialist hero. He has his own code (sometimes questionable); he is cynical; he does not suggest there are higher motives for choosing sides beyond personal gain; however, he often has a soft spot for the oppressed, enough of a soft spot so that we recognize that he may be bad, but he's not the bad guy in the film.

The world we see in Sergio Leone's westerns (arguably his masterpiece is Once Upon a Time in the West, though The Good, the Bad, the Ugly is probably his most popular) is bleak, as bleak as the Spanish plains. Life and the land and the people are hard and violent. The hero is the one who can toss off wicked one-liners and out-think and out-gun his opponents while just looking so cool in the process. This is the formula for the action-movie star (from James Bond to the Terminator robot) even today.

the ramen western (and other ramen westerns)

It's hard to think of Juzo Itami's Tampopo (1985) as a western or as a samurai/ronin picture, but it certainly fits the formula. A stranger, Goro, wearing a cowboy hat comes to town in an 18-wheeler with bull horns strapped to the radiator. He comes across a woman, Tampopo, who must run a noodle shop after the cook, her husband, dies. Unfotunately, she has not been trained in the code of the noodle-maker. Goro just so happpens to have the skills of a master, and he is willing to take on this young woman has his apprentice. This might remind you, so far, of Mr. Miyagi (Pat Morita) training the young Daniel Larusso (Ralph Maccio) the skill of hand-to-hand combat in The Karate Kid. Or it might remind you of the wizened Yoda teaching young Luke Skywalker the ways of the Jedi (bushido? or, later, Obi-Wan Kenobe sharing the mysteries of The Force in Star Wars. Well, it is the same idea. The young hero is initiated by the master.

I'll stop with just that much. Tampopo is an odd film with humor, sex, and lots of food. Its roots are partly in the eastern; the film was advertised as the first "ramen western."

That being said, another sub-genre of the martial arts film (we are in the realm of sub-sub-genres now) actually took this name--the ramen western. Often discussed in this category is Jee-woon Kim's The Good, the Bad, and the Weird (Joheunnom nabbeunnom isanghannom, 2008). The easiest thing for me to do here is to copy the summary/teaser from imdb.com: "A guksu western. Three Korean gunslingers are in Manchuria circa World War II: Do-wan, an upright bounty hunter, Chang-yi, a thin-skinned and ruthless killer, and Tae-goo, a train robber with nine lives. Tae-goo finds a map he's convinced leads to buried treasure; Chang-yi wants it as well for less clear reasons. Do-wan tracks the map knowing it will bring him to Chang-yi, Tae-goo, and reward money. Occupying Japanese forces and their Manchurian collaborators also want the map, as does the Ghost Market Gang who hangs out at a thieves' bazaar. These enemies cross paths frequently and dead bodies pile up. Will anyone find the map's destination and survive to tell the tale?" (jhailey). Yes, it sounds like a mix of a whole bunch of movies, but these South Korean movies pay homage to the spaghetti western which pays homage to the eastern. The formula, with many variations, persists.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)