"elementary, my dear Watson"

this oft-quoted line never appears in the Sherlock Holmes canon

If you walk into a brick-and-mortar bookstore (there are still some in existence), you will likely see that one of the larger sections is devoted to mystery and crime. In both literature and film, this is a hugely-popular genre, and it has been for a very long time. Many credit Wilkie Collin's The Moonstone (1868) as the earliest detective novel in the English language, but the real action started about two decades later. The first Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, appeared in 1887 in Beeton's Christmas Annual, and the handful of novels and dozens of stories that followed were serialized in various magazines and journals. It was this creation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle--Sherlock Holmes--who created the first powerful movement of mystery fanatics (fans).

How to define a fan: Holmes' readers would not let the detective die!. About mid-way through the series Conan Doyle (whose real passion was for paranormal activity) had had enough. He sent Holmes to a violent, watery death wrestling with a criminal over a waterfall in "The Adventure of the Final Problem" (1891). And then the letters started pouring in. Children in America pleaded with Conan Doyle not to let the detective die. Readers who were convinced Holmes was, in fact, a real person, wrote hysterical letters insisting that Conan Doyle find out what had happened to him. For three years the author and his publisher were deluged with letters pleading, cajoling, threatening that Holmes must not die. And in 1894, with "The Adventure of the Empty House," Holmes returned with a fairly ridiculous story about where he'd been for three years, though readers didn't care; they had their hero back.

Holmes, the first professional consulting detective, is a master of disguise, boxing and forensic sciences; his habits are quirky (he takes drugs when bored, screeches out tunes on a priceless violin, smokes and lounges around his apartment where he sometimes creates chaos experimenting with chemicals or firearms. His knowledge is vast but only on subjects he finds useful to crime solving (distinctive ash from different cigarettes, the location of specific combonations of mud around London, unique characteristics of handwriting and fingerprints (note this was before fingerprinting was an accepted forensic science). Only a puzzle can drag him from 221-B Baker street, but when he has a question that needs to solved, he is filled with frenetic energy and is keenly focused. His real genius is his amazing analytical skill. His ability to solve complex problems and to draw conclusions from observations that mean nothing to the average observer seem near-magical. Here is a typical Holmesian pronouncement from A Study in Scarlet:

"You appeared to be surprised when I told you, on our first meeting, that you had come from Afghanistan."

"You were told, no doubt."

"Nothing of the sort. I knew you came from Afghanistan. From long habit the train of thoughts ran so swiftly through my mind, that I arrived at the conclusion without being conscious of intermediate steps. There were such steps, however. The train of reasoning ran, 'Here is a gentleman of a medical type, but with the air of a military man. Clearly an army doctor, then. He has just come from the tropics, for his face is dark, and that is not the natural tint of his skin, for his wrists are fair. He has undergone hardship and sickness, as his haggard face says clearly. His left arm has been injured. He holds it in a stiff and unnatural manner. Where in the tropics could an English army doctor have seen much hardship and got his arm wounded? Clearly in Afghanistan.' The whole train of thought did not occupy a second. I then remarked that you came from Afghanistan, and you were astonished."

"It is simple enough as you explain it," I said, smiling. "You remind me of Edgar Allen Poe's Dupin. I had no idea that such individuals did exist outside of stories."

The film Holmes I grew up with (watching the black-and-white movies replayed on television) was Basil Rathbone (with Nigel Bruce and his portly, loyal, bumbling Dr. Watson). Some of the 1930's / 1940's films were set in the Victorian era (or thereabouts), but by the last few years of WWII, Holmes and Watson were re-invented as protectors of the Allies against evil Nazi villains. These were powerful morale boosters, and at the ends of the movies (which are sometimes still shown intact) there are urgent calls to "Buy War Bonds in This Theater!" Our reading, "The Adventure of the Dancing Men," was modified to become "Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon." Complete with villains running through secret passages and gangs of plain-clothes SS agents the movie revolves around the consulting detective's keen mind. He must solve the mystery of the puzzle of the matchstick men, but in this case, these are clues to the location of parts of a missing bomb site invented to allow the allies to drop bombs on Germany with a deadly accuracy not possible with 1940's technology. Of course the Nazis want to get to the invention first, and there is a deadly chase punctuated with traps and disguises. In the melodramatic-though-patriotic ending of the film, Holmes and Watson cheer on a wave of bombers crossing the English Channel to wreak havoc on the German cities. There are references to Coventry and Bath (two non-military English cities devestated by German bombings), and Holmes quotes a heart-tugging, nationalistic speech from Winston Churchill.

The fascination with this incredibly clever puzzle solver was such a success, that the formula has been copied by hundreds of writers and filmmakers. In America, for example, Jacques Futrelle mimicked the Holmes formula with Professor Augustus S. F. X. Van Dusen "The Thinking Machine" (well worth reading), and from 2008 Simon Baker has played Patrick Jayne--a Holmesian consultant to a homicide division--in the T.V. series The Mentalist. There are Holmes museums (221-B Baker Street has been recreated above a pub near Picadilly Circus, and there is a placque showing the flat would have been , if it every existed, on the real Baker Street in London. There have been plays, numerous films and television shows; there is a Sherlockian Society (peopled with many famous writers and other celebrities), and a number of famous fan writers (Ronald Knox, Michael Crichton, even Stephen King) have written Holmes stories (that range from traditional mysteries to supernatural and even sci-fi works).

And he's still with us. Robert Downey, Jr. and Jude Law are the newest film versions of Holmes and Watson. BBC Television has had a number of series on Holmes; the most recent stars Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman. The fans just keep coming.

"down these mean streets"

People often think film noire (literally "black film") got its name from the dark, shadowy settings and actions from the hardboiled detective movies of the 40's-50's. There is no doubt that the works are about dark deeds in dark places, but the term actually comes from Serie Noire--a 1945 French edition reprinting some of the hardboiled detective works of Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammet and others. Film noir was coined by a film critic a year later. Why There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry Santa Ana's that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands' necks. Anything can happen.

The writing is witty, edgy, vivid, direct, powerful, and the hardboiled detectives at the center of these works are the same.

There is also a sexiness about the movies that you certainly don't find in Sherlock Holmes. The heroes are physical presences who move through a world of crime and corruption. They are eductated in the streets rather than universities, and they can take a punch or a bullet and deliver the same. They fall for dangerous dames (who often get them in trouble and just as often are the cause of the trouble), but they never exploit. Uncorruptable, tenacious, with a strong internal moral code, these private eyes are the successors to the knights of the middle ages, the western heroes making a savage land safe for the civilized people who rarely know that they are being protected from the dark underbelly of society. In The Simple Art of Murder, his major analysis of the sub-genre, Chandler had this to say about the hardboiled detective hero:

...down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. He is the hero; he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honoróby instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it. He must be the best man in his world and a good enough man for any world.

He will take no manís money dishonestly and no manís insolence without a due and dispassionate revenge. He is a lonely man and his pride is that you will treat him as a proud man or be very sorry you ever saw him.

The story is this manís adventure in search of a hidden truth, and it would be no adventure if it did not happen to a man fit for adventure. If there were enough like him, the world would be a very safe place to live in, without becoming too dull to be worth living in.

Exploring the gritty side of political and legal corruption, mob/gang activity and white-collar crimes the hardboiled detective is still popular in literature, and filmmakers still use the lush, artistic film noir style (it is style of Ridley Scott's Blade Runner, for instance). The classics are still amazingly effective, though. Here is a link to a top-fifty fan favorite list at IMDB: Top-Rated "Film Noir" titles.

"shaken, not stirred"

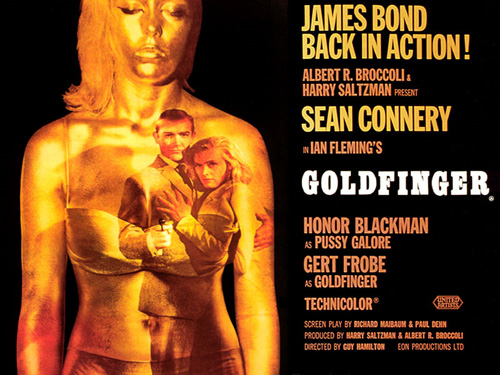

In 1953 Ian Fleming's Casino Royale was first published. It was the first appearance of James Bond, agent 007 on Her Majesty's Secret Service. In 1962 Sean Connery appeared as the first film James Bond in Dr. No, Fleming's sixth novel. Fleming died in 1964, just two years after the first film, but the character did not die with him; other writers still pen Bond stories; Connery has given the role over to half a dozen other actors (such as the current Daniel Craig). There has been a long love affair with this cool, British secret agent.

Bond is a crimefighter on another level. Yes, like the detectives he takes punches, drinks copiously (though his liquor is not the straight-up bourbon of Chandler's world):

A dry martini,' he said. 'One. In a deep champagne goblet.'

'Oui, monsieur.'

'Just a moment. Three measures of Gordon's, one of vodka, half a measure of Kina Lillet. Shake it very well until it's ice-cold, then add a large thin slice of lemon peel. Got it?'

'Certainly monsieur.' The barman seemed pleased with the idea.

'Gosh, that's certainly a drink,' said Leiter.

Bond laughed. 'When I'm...er...concentrating,' he explained, 'I never have more than one drink before dinner. But I do like that one to be large and very strong and very cold, and very well-made. I hate small portions of anything, particularly when they taste bad. This drink's my own invention. I'm going to patent it when I think of a good name.' (Casino Royale)

How else can one put this? James Bond has class. He's smart, witty, suave, handsome, sexy, deadly, icy-cool in a crisis (for example, when a laser beam is about to bisect him, starting in a very uncomfortable spot, or when he's chained to a nuclear device that is ticking down to explode--both in Goldfinger. Ladies love him; he has the coolest toys (an Austin-Marti with bullet-proof shield, oil slick, rotating license plate, even an ejector seat); he travels to the most exotic places--Istanbul, Monaco, the Bavarian Alps, a Japanese fishing village, the Carribbean, St. Petersburg. His accent is British silk to match his perfectly tailored suit.

But the why of James Bond is international crime and terror. Fleming and the earlier filmmakers created a character for the Cold War era. The western powers (notably England and America) were in an undeclared, underground war of espionage. Soviet, communist Chinese, and other nations that were potential threats had their spies deep within the western governments, and we had ours in theirs. The cold war was a decades-long stalemate with global thermonuclear warfare creating international tension. How comforting it was (and still is) to think that there are agents for good ("good" means "whatever side is our side") maneuvering the secret, shadowy mazes of international power to prevent global crimes that would destroy our way of life.

Bond is not alone. John LeCarre (the author's actual name was David Cornwell, and he created a pen name to write his spy novels, such as The Spy Who Came in From the Cold as he was actually working for Britain's secret MI5 and MI6), Robert Ludlum (who gave us Jason Bourne) and others were / are still active in the spy genre. Nowadays the enemy is not SMERSH or SPECTRE or some communist group; the enemy shifts with new headlines (Al Queda terrorists, for example, make likely subjects in current espionage thrillers). The spy series was an especially-popular television genre in the 1960's (following the success of the first Bond films). My favorite was The Man from U.N.C.L.E. (United Network Command for Law Enforcement) starring Robert Vuaghn as Napoleon Solo and as David McCallum as Ilya Kuruakin, a Russian on our team. And there was I Spy, starring Robert Culp, though it actually gave national attention to a young Bill Cosby.

The secret agent, then, does the job we can't giving us at least the illusion that there is some power out there dealing with international powers beyond our control, even beyond our imagining.

"you gotta ask yourself, do you feel lucky, punk?"

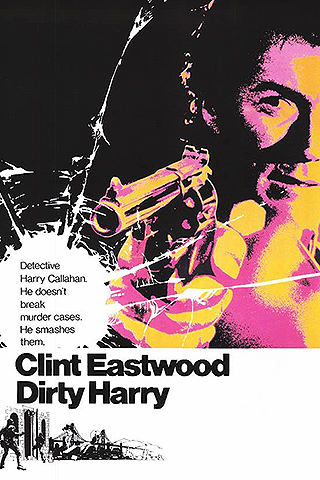

In 1971 Don Siegal was going to make Clint Eastwood even more famous as Detective Harry Callahan in Dirty Harry. Loosely based on the search for the real-life Zodiac Killer, Harry scours the still-mean streets to find Scorpio, an ex-Vietnam war veteran who snipes from rooftops of San Francisco and kills innocent victims with a high-powered rifle. The difference here is that Harry is not a private detective; he's a cop.

In a then-shocking scene from the movie, Siegal has the rifle pointed at the camera, at the audience. The message is clear: we are all the vicitims now. We need someone to protect us, and Harry, with his .44 Magnum, his steel-blue eyes and his rock-solid fearlessness is that protector.

And the criminals come in two forms. Yes, they are the punks and thugs and gangsters and mobsters and psychopaths among us, but they are also the businnesses, institutions, politicians. Harry's larger conflict is not with Scorpio; it's with the bureaucracy of the SFPD that hamstrings honest police with so many regulations and restrictions (most often designed to be politically correct and make the department and the mayor "look good"), that they won't chase a mugger for fear that they will have to fill out reams of paperwork, take sensativity training classes, face suspension and lawsuits.

The movie does not flinch at the notion that there are rogue cops. In fact, one of the sequals, Magnum Force, is about an elite core of killer cops who take the law into their own hands. But it also does not adopt a 21st-century notion that cops are somehow all to be distrusted. And trying to make policing somehow a polite and gentile occupation that necessitates going through channels and bales of forms to be effective, where clever lawyers and politicians asking for favors can put criminals back on the street is one of the problems.

It's no accident that one of the most popular films of 1974 was Michael Winner's Death Wish, which featured Charles Bronson as a one-man vigilante army cleaning up his crime-filled streets after his wife is murdered and the police can't put the muggers/murderers away.

This particular film, the first in a series, is a blend of elements. It's graphically violent. It's what film noir would have been if the Hays Code had not been in place in the 40's (in fact, you see the graphic nature in later film noir works such as Roman Polanski's Chinatown). That may have actually been a detriment to the classic noir films which had to use cleverness and suggestion instead of blood and gore. But a post-Vietnam America was now littered with graphic violence. The news was in-yer-face focused on scenes of escalating drug wars and the Manson family crimes. The movie is also allusive and artistic (there is a scene where Harry has to race to pick up sequential phone calls (from pay phones; there was not the ubiquitous cell phone in 1971) around the city that has been compared to Christ's stations of the cross). There is the wit of film noir ("Do you fell lucky, punk?" and the later "C'mon, make my day" one-liners of Harry Callahan signled a trend in action-film one-liners, such as Arnold Schwarzenegger's "I'll be back" and "Hasta la vista, baby").

Harry is the knight, the western hero, the hardboiled detective of our times. He does the job nobody else wants, and he does it with integrity following an unshakeable internal code. The work he does is not pretty, but it works. It may be politically incorrrect to even acknowledge the need for a Harry when we have seen corrupt and violent police commit crimes of their own in the name of policing, but Harry is not on the streets to torture and kill for the fun of it or just to exercise the power behind a badge. The streets (and the board rooms) he polices are filled with real danger, and he is there to save us.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)