what did we learn last week?

Quite possibly we learned lots of things, but the two ideas that I hope stood out most are:

- the stories (poems, plays, novels) that get shoved in these literature anthologies are not always simple; they contain ambiguity; they require reading, re-reading, note-taking, thinking.

- to try to make sense (get to the meaning or theme) of these stories, you need to read really, really closely, just as I went through "All About Suicide" almost sentence by sentence.

If you casually breeze through the stories, of course you are likely to throw up your hands and say, "I don't get it." If we go back to that car analogy from Lecture 1, it would be like going out to your car, turning the key, hearing the ker-THUMP, throwing up your hands, and saying, "Something's going on, but i don't know what it is" and then just driving away ignoring the (ominous) noise.

Analysis takes some time, but the good news is that there are certain elements you can look for to make the process easier. Your textbook breaks down several literary elements that may be significant in the story you are reading. For example, "How to Talk to Your Mother (Notes)" would not work if Ginny were born in 1995; time and place are important in that story, but sometimes setting is just setting and not particularly significant. Do go over the elements, and use your text to help you, but here is a method that works pretty well and works quite often, and it's simpler:

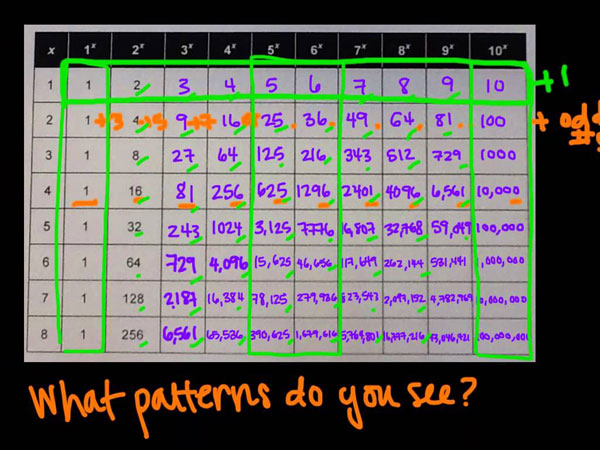

look for patterns and peculiarities

But let's come back to this in a bit; let's go backwards (this lecture is going to go backwards for a bit)

the first (quick) reading

Your text explores how to read through, take initial notes while reading actively, and so on. If the goal is to discuss or write about the story, then you will need to figure out what it means (and, remember, it can mean more than one thing). That conclusion can usually be framed in a thesis statement:

The repetitious plot structure of Luisa Valenzuela's 'All About Suicide' suggests that no matter how many times someone tries to make sense of suicide, it cannot really be fully known."

But wait, that was not immediately apparent on the first quick reading. That took a whole lot of analysis to arrive at. True. The thesis is rarely created after the first quick reading. It comes later. Before that, you need to ask questions about what you read. If we can eventually answer those questions, the answers will become the thesis statement(s) that will launch your discussion or essay. We are going to try this out with John Updike's "A&P" (be sure you have read the story, or this will not make much sense).

So I read the story, "Blah, blah, blah." Stuff happens to people I don't know. Sammy is the narrator, and at the climax (the point where the story makes its ultimate turn; typically, the main character makes a choice or fails to) of the story he quits his job at the supermarket because he feels his boss is embarrassing these three girls in bathing suits. After that he goes out to the parking lot hoping to see the girls, but they are gone (those things that happen after the climax are called the resolution).

Not much happens. All things considered, I would rather watch an episode of Twin Peaks or Sense8. Still, the story is in the textbook, and it was assigned, so I better look for something here. I have a few immediate questions:

- Is Sammy just a dumb kid who quits his job, or is he acting out the classical role of heroic knight in shining armor coming to rescue damsels in distress?

- Is Sammy really all that upset that he now has no job?

- Why the heck are those girls in the store "in nothing but bathing suits" (142), and why is everyone making such a big deal out of it?

Note: for that third question I actually wrote down a note, a quotation from the story; I am ahead of the game. WOOT!

I could probably come up with more quick questions, but this is plenty to start with. Now it's time to try to answer the questions. For this lecture, I will mainly look at question 1: "Is Sammy a hero or not?" It's time to go back to

look for patterns and peculiarities

Especially in shorter fiction (short stories, poems, one-act plays), if an author takes time to repeat something (a kind of image, a word or phrase, etc.), it is meant to stand out. Likewise, anything that is odd, weird, peculiar will pop out, and it is very rare that that is accidental. The author is saying, "LOOK AT THIS!"

If we are looking for evidence to answer our question, "Is Sammy a hero?" we need to think about what makes a hero. Here are some things that come to my mind:

- a hero is self-sacrificing

- a hero does not expect to be rewarded

- a hero has a "good" character

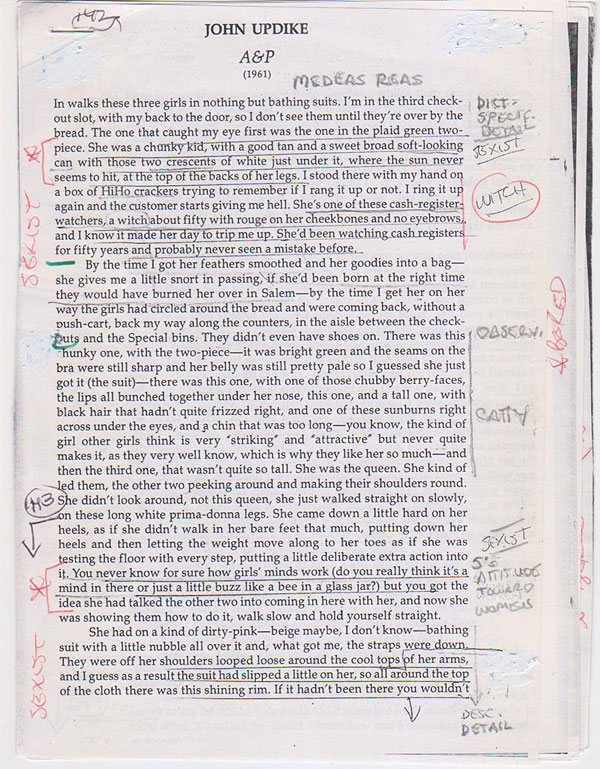

That's enough to get started with. Now the long part. I need to go back through the story, taking notes (this is very important; you will need these notes later) looking for things that are described/narrated that tell me if Sammy is self-sacrificing, expects no reward, has a heroic character. This story has a lot of material that addresses these points, and here are my notes just for one page of the story (I like to photocopy the story and then write on the photocopy, but feel free to mark up your textbook; you paid for it):

That is a lot to work with already, and there are examples like this throughout the story. Don't worry if you can't decipher my sloppy writing and abbreviations; I will explain examples in a bit. If your notes are sloppy, that's fine. Just be sure they make sense to you, and be sure you have enough notes--more is (usually) better.

Just on that first page, there are several patterns that help answer some of our questions; it is time to fill in lists that relate to the qualities I am looking for and tie them to annotations (highlights, underlining, marginal notes) I made on the story:

a hero has a "good" character

Sammy is a sexist; he complains about McMahon checking out the girls, but he's looking at their flesh: "She was a chunky kid, with a good tan and a sweet broad soft-looking can with those two crescents of white just under it where the sun never seems to hit, at the top of the back of her legs" (142).

He is even more sexist when he says, "You never know for sure how girls' minds work (do you really think it's a mind in there or just a little buzz like a gee in a glass jar?" (142)--he is saying girls have no brains!

He is in a service job, but his service is lousy, and he is disrespectful to customers; he calls one woman a witch: "She's one of these cash-register watchers, a witch about fifty with rouge on her cheekbones adn no eyebrows" (142). Later he is going to call customers "sheep" (143, 146), "house slaves with varicose veins" (143) and "pigs in a chute" (146). He doesn't seem to have a very good character.

a hero is self-sacrificing

I am not going to go through all of the examples; you can do that on your own. Here is a quick run-down, though: Sammy does not really like his job, and he did not seek it out in the first place (his parents got him the job), and it is not as if he will never work again. Find quoted examples of each of these statement.

a hero does not expect to be rewarded

Again, you can fill in this section, but there are several examples showing he is disappointed he is not going to get a date or a kiss or at least recognition: "The girls, and who'd blame them, are in a hurry to get out, so I say "I quit" to Lengel quick enough for them to hear, hoping they'll stop and watch me, their unsuspected hero" (145).

So far, I am building a pretty strong case for "Sammy is NOT a hero," and the list will grow as I find more examples from the story. Is there anything in the story that supports the other position--"Sammy is a hero"?

Even though he doesn't really like it, Sammy does give up his job, and his parents will probably yell at him, and he won't have gas money to take Peggy Sue to the drive-in until he gets another job.

And then there is the peculiar (remember, we are also looking for things that are peculiar) last line of the story: "and my stomach kind of fell as I felt how hard the world was going to be to me hereafter" (146). This doesn't even make much sense; it's melodramaatic, and Sammy is young, but quitting this job will not destroy his life. I could ignore this or try to make sense out of it. It's best not to ignore it.

First, the story is a flashback to an earlier time. We know this because Sammy says, "Now here's the sad part of the story, at least my family says it's sad but I do't think it's sad myself" (144). Sammy can't know his family's reaction unless the story is being told after the events he describes. Those events end before he goes home. That means he has had some time (how much?) to discover "how hard the world was going to be." To find out why it was hard, we should go back to that key moment when Sammy quits. Lengel knows Sammy is being rash, tells Sammy he will feel this for the rest of his life and that he does not really want to do this. Sammy thinks, "It's true. I don't. But it seems to me that once you begin a gesture it's fatal not to go through with it" (146).

So what has just happened? Sammy shows he has integrity. He makes a gesture, and he does not weasel out of it. This is the event he is looking back to where he knows he will live life as a person who keeps his word, and that is harder than not following through.

so is Sammy a hero?

My short answer is, "Yes." He is a rare person who will live his life with integrity. I've taken enough notes above to make the case for that.

so my thesis should be...?

The word tricky will come back in play this week.

After taking all of my notes, on all of my questions, I have to settle on a topic and devise a thesis. The thesis is my subject plus the point/claim I will attempt to prove about my topic. The subject is the author and story title, and the point/claim is the conclusion I arrived at about Sammy's being a hero or not. It will look something like one of these:

In John Updike's "A&P," the main character, Sammy, is a hero.

In John Updike's "A&P," the main character, Sammy, is not a hero.

Why did I write both positions when I told you already I think the story is about a hero?

There is not necessarily one right answer. I will look over my lists. The list showing he is sexist, disrespectful, bored, disinterested in his job, wishing for recognition will be a very long list with lots of examples. I can easily get a paragraph on each of those points. This lists suggesting he is a hero is really short. Can I get a four-page paper out of that? It is possible, but it will be hard. My inclination is to make life easy for myself (I guess I am not like Sammy), so I will probably select the following:

Although Sammy, in John Updike's "A&P," does give up his job when he feels Lengel is embarrassing three customers, his actions are not really heroic.

I've added the opposing position with my "Although" statement, and I've clarified my position with a little more detail. Note that the author and title are both in the thesis. It is clear what point I am going to develop and illustrate in my paper, and that point will be the focus of the whole paper; I will not take both sides. Could you take the harder side? Of course!

on to the essay (this lecture is nearly done...*whew*)

Now you take the material from your notes, sort it into meaningful categories (Sammy is a sexist; Sammy is disrespectful, etc.) and build your paper using the OBSERVATION-QUOTATION-EXPLANATION formula. After your paper's opening (which should be livelly, if possible, and should relate to the thesis somehow), you will put in your thesis. Then you will suppport that thesis with various claims (obervation) which you back up with quoted/documented examples from the text (quotation) and then transitoinal sentences taht explain how those examples fit and then lead on to your next point (explanation).

I call it a formula, but it's really more of a general guideline. It allows you to get enough of your own thinking into the discussion/essay, and it shows that you can support your conclusions with evidence (and know how to document that evidence).

If you would like to see what the beginning of an essay on "A&P" would look like, click on this link (file is a rich-text file), and it is in MLA format.

Looking at the sample essays in the textbook will give you even more ideas about how to develop a literary analysis :)

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)