i don't get it

In my face-to-face class, I begin this section having students read one of my favorite poems, "The Windhover," by Gerard Manley Hopkins. Please read it before you move on (it's in the textbook).

I have students take out a piece of paper and anonymously write "your thoughts about poetry--write anything you feel like." You could do this too, or you can just think about it.

Three of the most-common items that appear on these sheets are:

- I don't get it!

- It's just random emotions.

- I don't like it.

Some of you may (maybe not) have finished "The Windhover" and agreed with that first statement--"I don't get it!" It is a challenging poem. That may have triggered the third statement as well--"I don't like it." Poetry seems hard, certainly harder to "get" than prose. Sometimes the words themselves are unusual (if you were taking "The Windhover" seriously, you may have had to look up several words), but there are other techniques that seem alien to us; it just does not (usually) read like a story or a newspaper article. Some of these unfamiliar or unnatural (seeming) techniques can be off-putting to some readers, but, really, not all poetry is hard. Try this brief poem by Ogden Nash (who actually made money as a poet):

"Fleas"

Adam

Had'em

It's short and funny, but is it really a poem? It rhymes, it has a regular rhythm, it gets its point across in a compressed form; sure it's a poem. Is it a great poem? I shall leave that decision up to you. It is certainly not hard to understand.

what is poetry?

Poets and scholars do not agree on a single definition. Poetry is a lot of things. My favorite defintion is from an essayist named Jeremy Bentham (who happened not to like poetry); he wrote, "Poetry is when the lines do not reach the edge of the page." That defintion is almost always true, and this unusual typography (placement of words/lines on the page) allows us to recognize poetry from a distance, even if we are not close enough to read the words.

Most of you probably recognize poetry, and most of you probably love(d) poetry (past and present tenses). When you were a child, you may have sung skipping rhymes ("Blue bells / Cockle shells") or read nursery rhymes ("Pat-a-cake, pat-a-cake, baker man / Bake me a cake as fast as you can"). Many loved books like Goodnight Moon and Shel Silverstein's Where the Sidewalk Ends. The question is not did you like poetry, but what happened? Possibly nothing. I suspect most of you still love poetry; you even choose to memorize it when you sing along to your favorite songs on your MP3 players or smart phones.

Poetry is not just one thing. You may not have enjoyed the poetry trotted out in your English classes, things about irrelevant-seeming wheelbarrows and people standing at forking paths in the woods and ravens who somehow keep repeating, "Nevermore." You probably did enjoy the lyrics (poetry) of "Cheerleader" or "Take me to Church."

My goal is not to make you like all poetry. I don't like all poetry. Who does? But you do embrace some poetry as part of your past and part of your present, so let's see if we can figure out how poets choose to make sense in a different way from prose.

what about the second statement?

"It's just random emotions." Well, no. It isn't.

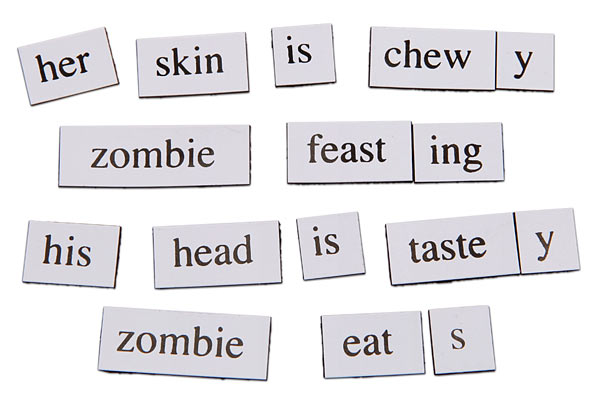

First, most poetry is not at all random. Some is (found poetry, for example.); however, even the magnetic poem at the top of the page shows the writer made quite a few choices. Poets work hard, often taking as long writing a short poem as a story writer takes to polish a longer story. There are lots of decisions to make.

Second, not all poetry is emotional. Look again at "Fleas" above. It is funny/intellectual, not emotional. Conversely, many prose works are emotional.

"l(a"

As I mentioned, poets use different techniques the way painters use different tools and color palettes (yes, many students agree they don't "get" art either, but I will let the other side of the campus help you with that language).

There is a very short, and very odd, poem by e e cummings that has appeared in nearly every English 102 anthology I have used or read (it is in your textbook as well). It is untitled, and when a poem is untitled, the first line of the poem is used to designate the name of the poem. This one is called "l(a" and it is a great place to start.

l(a

le

af

fa

ll

s)

one

l

iness

I know, some of you are thinking, "WHAT THE HECK IS THAT? THAT'S NO POEM!"

cummings (no cap) was a very playful poet. He loved manipulating typography (word/line placement) and punctuation to add meaning to his works, and the results are rarely as nutty-looking as this. But this poem took a lot of thought, and if we look at it closely, we can see that just seventeen characters can explode out into a lot of meaning.

I was not born in Japan, so I am not used to reading top to bottom (though East-Asian writing is also often situated horizontally, yokugaki in Japanese, for instance. So my first inclination is to make this look familiar to me. I will re-situate it so that is moves left-to-right horizontally:

l(a le af fa ll s)one l iness

Hm...

The breaks between groups of characters are odd, but I can make out some words here if I try. Inside the parentheses, I see, "a leaf falls"; outside the parentheses, if I move the "l" over, I see "loneliness."

WAIT JUST A MINUTE! How can you just move the "l" over? That seems random. But it isn't, and here is where that grammer that was taught back in elementary school finally comes into play. A parenthetical expression (expression inside parentheses; it could also be set off by commas) interrupts a larger phrase or clause (don't worry; an example follows, but THIS is a parenthetical expression). It is not necessary to the larger construction, but it does add what I like to call "bonus information." Here is a simple example:

John (who happens to be extremely handsome) is my teacher.

The root of that sentence is, simply, "John is my teacher." The stuff inside the parentheses does not change that. It only adds bonus description, so it can be lifted out, and what is to the left and right of this expression comes together to create the main idea.

That's exactly what cummings has managed, and it was certainly not accidental. "A leaf falls" is really an example contained within the larger idea of "loneliness." Does it make sense? Does a falling leaf really have anything to do with loneliness? When a leaf falls, it is separated from its leaf "family" in the tree, sort of like a young man or woman leaving home to go off to college. It's kind of sad. Making this comparison even sadder, when a leaf falls, it is no longer going to recieve nutrients from the tree; the student is on his/her own, which is hard, but the leaf has it even worse; it is, in effect, dead or dying :(

Who really needs poems about leaves and loneliness? Well, arguably, who needs much of anything? People like to try differnt forms of communication. The poet (like the painter) is taking an abstraction--loneliness. This is a feeling, so it cannot be fully expressed in words (or paint). The best that can be done is to make the un-known make sense through the known. The alien that everyone seems to talk about comes to earth and asks, "What is this thing you humans call 'loneliness'?" What could we say? "Well, when you are flying in formation with your space armada, you have communication and support, but when you have to fly a solo mission, you have only yourself to rely on, and that may cause un-ease." We use comparison to explain abstractions.

Fine, but why couldn't Cummings (with a capital C) not just have written easy-to-understand prose: "Loneliness is like a leaf falling" instead of the crazy column of letters? It seems like poets are trying to 1) hide meaning, 2) confuse us.

Or perhaps that crazy placement of characters on the page adds to the meaning of the poem, reinforces the main idea. If we look even more closely at the poem, other things emerge. Most "lines" are two characters long. The first is not (it contains the left parenthesis and two letters), and near the end there is a line with three letters, a line with one letter, a line with five letters. Do those last three lines add to the poem?

one - a number, singular, alone; Three Dog Night sang "One is the loneliest number..."

l - looks like the number 1; in fact, in the days of typrwriters, lower-case l was used instead of 1

iness - the state of being "i" (myself) alone

"le" and "la" are also singular pronouns in romance languages (French, Spanish).

Reading from top to bottom makes our eye follow the pattern the leaf falls.

Even the whole poem looks a bit like a big number 1 (that may be pushing it).

this is fantastic, or is it frightening?

It's proably a little bit of both. cummings managed to use just seventeen characters and reinforce his idea over and over and over; he compressed MAXIMUM MEANING into those very few characters. None of it was random or accidental, and it likely took him a very long time to compose these seventeen characters.

To make sense of it I spent nearly the time/space I devoted to analyzing the short story "A&P." But I was able to make sense of it. Two things were required:

Poetry needs to be looked at very closely, bit by bit. Trying to read a full poem and then immediately announcing, "This means XYZ" is not going to work. It requires thought, note-taking, picking apart lines and phrases and even words. You need to read that closely.

It often takes as long to read, analyze, explain a short poem as it takes to read, analyze, explain a short story. That does not mean you will always enjoy spending all of that time and effort, but it will allow you to understand how some of this works.

Does that guarantee you will all be able to make sense of all poetry at the end of this section? No. Like most complex things, it takes time and practice to hone your analytical skills. If you are pretty good at _________ (fill in the blank with hockey, guitar, lacrosse, cooking, weaving, whatever), remember what it was like when you first skated (your ankles throbbed) or first picked out notes on a Stratocaster (your fingers bled), and so on.

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[readings]](button13.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)