another look at literature in context, but first...

For this week's play, it is useful to know something about the Ancient Greek Theater. Not only will it show you some of the limitatons and some of the genius of that time/place, but it might also help you understand why the play is set up the way it is.

Feeling lazy, I decided to do a quick search, and rather than re-invent the wheel (er, the amphitheater), I found this Prezi thingey (the embed code didn't want to work for me, so I just added a link for those interested):

Here is an added thought on the structure of the ancient Greek dramas. Many students nowadays don't particularly like the poetic bits (prologos, odes, etc.) that separate the plot sections (episodia). Quite likely, audiences in Athens in the fifth-century B.C. preferred the poetic bits. This sort of contextual consideration is different from studying the historical, political, social, religious conventions of that time/place. Here are a few reasons why the poetry might have outshone the stories:

The audience knew the plot in advance; they'd seen/heard these stories many times growing up, so the story development did not hold a lot of surprises for them.

The physical nature of the theater made action (chase scenes, for example) nearly impossible; actors faced the audience and proclaimed their lines.

The chorus moved and (in later plays) sang (later accompanied by musical instruments).

It must have been much like going to musical theater in the 20th-21st centuries. In a play like Cats, Phantom of the Opera, or Rent, for example, it is the poetic parts (the songs) audiences usually come to watch/hear.

but let's not write off the plot

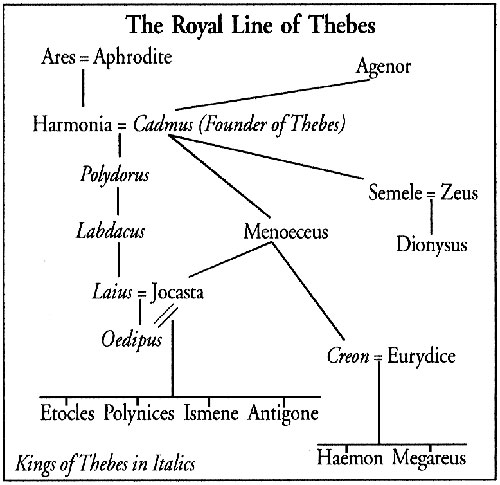

Sophocles's version of Antigone (pronounced "an-TIH-go-nee") is very neatly set up, and here we do want to consider the history, political, social, religious conventions of that time/place, because audiences in the 1970's (can you see why this play would re-emerge in so many college/university theater arts departments during the pinnacle of the feminist movement?) would have seen elements in the play that the ancient Greeks would not have.

As I mentioned somewhere else, that's OK. It is fair to look at a work of literature in different times/places to see how it speaks (often differently) to readers and audiences in those times/places.

But let's go back 2600 years or so. NOTE: this might help or further confuse you with Paper 3 :)

Let's add two more questions:

Is Antigone a hero(ine)?

Is Creon a villain?

My gut instinct is to say, "Yes and Yes!" However, literary analysis is generally not a gut-instinct sort of thing. Still, let's start with "Yes and Yes!" and see where it takes us (and the ancient Athenians).

Antigone represents family loyalty. Antigone stands up to a king whose law she disagrees with. Antigone champions women who have been controlled by men. Antigone recognizes that in order for her brother to enter Hades (not hell, just the after-world), specific rituals must be performed.

By all accounts, the ancient Greeks did applaud family loyalty, but they believed the individual never had as much value as the state (city/nation), so Antigone's trying to defy "law" would make her a villain (even though her loyalty is laudible). In her attempt to defy the king (even if he is a jerk), she is challenging the state. Feminism was not a key movement in ancient Greek culture; in fact, women were about on par with slaves. A defiant female would not endear herself to the audience, and a woman shouting down a male king would probably get booed (yes, times change). In terms of performing religious ritual, the Greeks always saw the will of the gods/goddesses as more important than the daily grind of humans, so church was more important than state. Antigone represents church; Creon represents state.

So where does that leave us?

Antigone's position on family loyalty > heroic

Antigone's stand on individual rights vs. the establishment/government > villain

Antigone's championing women > villain

Antigone's obedience to religious custom > heroic

It's 2:2, but we don't need a tie breaker because this is a heirarchical consideration: That list goes from least to most important (with women's rights not being a real consideration to the ancient Greeks): individual is least important; state is of secondary importance; religion is most important. Antigone is a hero(ine), maybe.

Add to that Antigone's bull dog approach to Creon, her meanness to her sister, her headstrong approach (she could have just quitely sprinkled dust and oil on her brother, and that would have satisfied the religious requirement; she did not need to get caught). How would that make audiences feel when they are uncomfortable with her position against the state and her stand on women's rights? I suspect audiences would be torn, and the "being torn" is what creates tension, AKA GREAT DRAMA!

How about Creon?

Creon's wish to bring Thebes out of chaos > heroic

Creon's refusal to listen to his senate/people and his lack of reason > villain

Creon's making a law that ignores the demands of religion > villain

Other stuff? > ?

He seems to be the villain, but what does "Other stuff?" mean?

I shall leave you with a thought, and it is the thought the ancients were left with; it may just show up in this week's discussion: Creon, at the end of the play, is not the same person that Creon was at the beginning of the play. Hmm...

![[schedule]](button12.gif)

![[discussion questions]](button44.gif)

![[writing assignments]](button41.gif)

![[home]](button21.gif)