beginning at the beginning...

I'm not old enough to know, but I'd wager that the first myths to be circulated were not origin myths / creation myths. The immediacy of survival or extinction would probably cause primitive tribes to wonder more about weather and food and geography. Thoughts of birth and death would have followed once the tribe had enough leisure time to just sit and wonder.

Still, the origin of all things has captured the imagination of people for at least tens of thousands of years. And it really is at the center of some of the most fundamental questions:

"Why is there something as opposed to nothing?"

"Who started it all?" (most often it's a "who" rather than a "what," but not always)

"Why did things turn out the way they did?" (was it chance, or was there a design?)

Certainly the most primitive people had little science to draw upon, so they created stories that made sense based on the things that they were able to observe. The many "cosmic egg" stories (see Phan Ku the Creator for an example) recognized that new life often came from eggs; the proportion of the ORIGINAL egg was larger, encompassing all things or, at least, the originator of all things (I'm sure they wrestled with the "which came first..." riddle from the beginning).

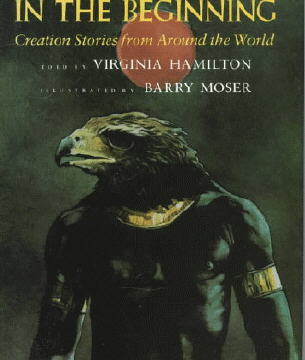

In the West the most common myths are those of the Hebrews (since Jews, Christians, Moslems are all Abrahamic religions, and these religions account for the vast majority of religious followers in the West). But there are as many orgin stories as there are cultures, even sub-cultures. Look over the examples from our text and from the online anthology, and you'll see that although there are differences (animals special to some cultures figure prominently in the creation myths of that culture; women are the creators in some cultures; the creator often sometimes just creates the initial order from chaos then leaves, and at other times the creator has a long-range design), there are amazing similarities from myth to myth.

Now before some of you get all upset about the word "myth"; it DOES NOT technically mean "something that is untrue" (so I am not slamming any religion when I talk about its myths). Equating myth with false is a newish concept. A myth is a story that explains why things are the way they are; it's a system of belief that is not supportable by the scientific method.

Technically, the Big Bang theory of the origin of the universe is not a myth; however, it is a story. It meets some of the scrutiny of the scientific method (stuff in the universe is, based on observations, moving away from other stuff); still, science is not made up of fixed truths. Remember that plane geometry and the idea that "the shortest distance between two points is a straight line" makes a great deal of sense in a fairly small location with fixed points; however, you need to take a bit of calculus to send a moving body (a rocket, for example) from a moving body (Earth) to another moving body (Mars), and if you just fire the rocket in a straight line, you are going to miss big time!

So science changes as new observations, new tools, new problems arise that make earlier ways of thinking inaccurate or incomplete.

Even if we accept the Big Bang theory as true, there are still the original questions that remain unanswered:

"Why is there something as opposed to nothing?"

"Who started it all?" (most often it's a "who" rather than a "what," but not always)

"Why did things turn out the way they did?" (was it chance, or was there a design?)

In other words, the Big Bang starts with a "singularity," but where did that come from?

The problems are complex, but they crop up early in human consciousness.

I was driving the kids to school, and my daughter, then aged seven, asked, "Dad (they call me "dad" :) if God created all things, where WAS God before all things were created?"

I didn't have the answer, but I've asked the question since I was very little.

At age seven my son asked, "Dad does the universe go on forever?"

I responded with a cautious-but-honest, "I don't really know; some people think so."

(after a pause) "Well, dad, if the universe goes on forever, where is it?"

In the end, the brain or mind knocks up against a barrier; I, at least, run out of rational answers. What's left are the myths, the sometimes-simple, sometimes-elaborate stories that symbolize cosmic events.

Yes, I know the word symbolize will irritate some, but even most orthodox religious realize that the "seven days" of creation in the Hebrew account of creation makes little literal sense before space or time existed. It does, however, correspond nicely to a unit that divides our year, which makes the explanation satisfying, orderly, meaningful.

![[schedule]](butsked.gif)

![[discussion questions]](butdisc.gif)

![[writing assignments]](butpaper.gif)

![[readings]](butread.gif)

![[home]](buthome.gif)