"I know who I am and who I may be if I choose"

from Don Quixote

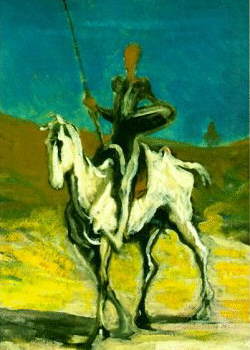

Although people will quibble (people do), in Don Quixote we come to the first major modern hero in the first major modern novel.

Quixote has been described as the most autonomous character in literature--a supreme example of the phenomenon by which a fictional character acquires a life of its own, independent of its inventor.

This caused some problems for Cervantes. Like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle who could not rid himself of Sherlock Holmes (many still believe Holmes and Watson are authentic historical characters), and like Frank Baum who thought he had done with Dorothy and her chums in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, the demand for Quixote was so great that Cervantes, protecting his interest in his creation, wrote two books, the second ten years after the first. If you read the entire second book you will find several barbed references to other writers stealing Quixote and publishing unauthorized books for which Cervantes got nothing; he wrote Book II to protect his investment.

And it was a considerable invesetment, an investment of time, hard work (writing is hard work), imagination, ingenuity, and sophistication.

The very frame of the book helps encourage readers to buy into the Quixote-as-real illusion. Rather than narrate, Cervantes appears more as a recorder of historical events, rumors, anecdotal material which may be genuine or may be apocryphal (how could it be genuine?). Chapter I of Book II is titled: "Put into a Book"; the modern self-reflexivity of this section predates authors such as Luigi Pirandello and Jorge Luis Borges by hundreds of years.

The style of the book is so varied and rich that it shows a masterful control of language which is manipulated to help the reader believe that the stories within the larger story are, well, stories; the larger novel, then, is the historical frame (Cervantes as editor) recounting the exploits of the imagined-real Quixote who lapses into delusion and memories from invented chivalric romances, ballads, etc.

It's more sophisticated than The Matrix, Run Lola Run, and Memento all woven together. And the story successfully carries us along with adventure, humor, thought.

Maynard Mack, et al explore the way that Cervantes uses satire and parody to poke fun at Quixote at times, while at other times turning the situation around to poke fun at those who would poke fun at Quixote:

Parody is ordinarily a magnificaton of the characteristics of a particular style to the point at which its absurdity becomes unmistakable--in the case of Don Quixote, the inflated highfalutin style of the chivalric romances. Yet apart from the early quotations from Quixote's readings, obviously inserted to parody that style, his own speeches in the course of the story and the general nature of his eloquence move increasingly away from parody toward a speech that registers both his delusion and the idealism that feeds it. The term "satire" is equally inadequate for describing Cervantes's tone. Satire, in its usual sense, aims to expose an object or a person to ridicule and censure with implicit reference to a higher standard of conduct. In Cervantes the case is more complex. The argument can be made, in fact, that Quixote, far from being an object of satire, unconsciously becomes the satirist--of, say, crooked innkeepers or aristocratic pranksters--by exposing their cruelty, childishness, and vulgarity. In addition, and more generally, Cervantes's complex attitude toward the world of medieval chivalry can hardly be considered unmitigated satire. The serious interest and the underlying importance of Quixote's actions and speech can be demonstrated by observing their effect on other characters, particularly Sancho, whose warm response to Quixote's genuine chivalry of heart should correct any tendency to identify the two men with a superficial polarity between idealism and realism.

Certainly the values that Quixote champions are the values that most societies at least pretend to support. His goal is "To right wrongs and come to the aid of the wretched" (1254). He speaks soundly of valor (1315) and a of a golden age which may never have existed but which is the goal of so many compassionate, gentle, charitable, peaceful people (1225). When he confronts the merchants and requires that they confess that Dulcinea del Toboso is beyond equal, they require that he show her to them; his reply gets at the heart of all faith (1200).

The book is not a simple comedy (though it is quite funny); it speaks of the complex quest of every individual trying to find value and meaning in life: "I know who I am and who I may be if I choose" (1181).

-- continued in next week's lecture

![[schedule]](butsked.gif)

![[discussion questions]](butdisc.gif)

![[writing assignments]](butpaper.gif)

![[readings]](butread.gif)

![[home]](buthome.gif)