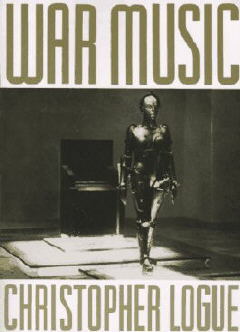

war music

I'm not necessarily endorsing Christopher Logue's 1997 poetic interpretation of Homer's The Iliad, but the title does capture the flavor of the book. At it's heart this is the story of a hero who shines with violence. Like the adept martial artist, Achilles's quest is to find harmony, a balance between his warcraft and a sort of inner peace.

The sub-title may be a tip-off to contemporary feelings about epics in general--perhaps we should chop out 2/3 of the story to satisfy the patience of modern readers. So much of the tales seem to be filler--long lists, repetition, things being described three different ways.

Some of the bits that modern audiences might consider filler are in large part due to the tastes of the target audience (Greeks from 8th - 6th centuries B.C.); they are also part of the conventions of the Oral Tradition in which these stories are rooted.

Homer (no, I'm not sure if Homer was one man, two writers, a woman; I'm not especially interested in the writer behind the works, just as I'm completely willing to believe that Shakespeare wrote his own plays and poems) wrote around the 8th century B.C. Twelve-hundred years earlier, Greece (Mycenae) had experienced a "Golden Age." These were the days of Minos of Crete (and later tales of the incredible labyrinth of the Minotaur). When this early Greek civilization fell, it ushered in a Dark Age (an age with no extant literature) that lasted until the time of Homer. Tales of ancient gods and heroes, of magical exploits and of historical events were passed along orally from generation to generation by storytellers.

Whoever Homer was, he did not invent the stories; he combined, edited, shaped, embellished, and put them into writing. So he borrowed heavily from these tales that had been preserved orally for hundreds of years. The writings of Homer and a new literacy formed basis for values and education in the next great era of Greek civilization located in Athens in the 6th century B.C.

Even though Homer's works were set down in writing, copied, circulated, most people during his time could not read. Storytellers continued to perform favorite bits of the epics to audiences. A competent story teller would have to know many, many tales; some of these stories were quite long and involved. To make his job easier, there were several conventions (by the way, these conventions are found in the epics of many cultures, not just those of the ancient Greeks).

Stock Items

The stock epithets (descriptive phrases used in place of names, often with three variations per character) allowed the storyteller to offer a little variety while extending the narrative. For us this can be confusing; we have to remember that the Achaians, the Daaneans, the Argives are all the Greeks). Zeus is sometimes called Cloud Gatherer, Storm Bringer, Thunder Shaker. Agamemnon is also knows as Atreides and Son of Atreas. There are also stock situations that are not realistic but which allow the storyteller to focus on a key event; for example, the armies often wait on the sidelines to watch single combat between two of the principles, and since one battle can be described in much the same way as another, the storyteller needed only to remember one plot idea and apply different names and a few different descriptive details to it.

Cataloguing

This was another opportunity for the storyteller to improvise. Whenever there was a list of weapons, a description of a feast, even a cataloguing of treasures (such as the description of Priam's loot or the detailing on Achilles's shield), the narrator can just describe whatever exotic thing might come into his head. The audience would have enjoyed hearing about all of the luxuries (most had precious few luxuries in their own lives), and the more elaborate the better.

Repetition

This is a plot device that creates continuity and emphasis. It's also a way for the narrator to extend the story while having to memorize less material. Read Zeus's instructions to Iris (155); then turn the page and see Iris's instructions to Priam (156). It's not deja vu; they are nearly word-for-word the same.

Elaborate Comparisons

As with the colorful, descriptive epithets, the poet and narrator used simile, metaphor, personification, conceits to add detail and extend the narrative. Short examples include "fish swimming sea," "winged words," "rosy fingered dawn," "yellow robed dawn." Some can get quite elaborate. Look at the extended description of light glancing off a shield (137), the nightmare image of Hector being stuck while hunted (143), and the scales of death (144). The detail is limited only by the invention and imagination of the poet.

epic proportions

The scope of The Iliad is huge. The stalemate siege of Troy lasts years; the Trojans want to be left alone; the Greeks ache to go home. The story extends beyond the human drama and involves the gods and goddesses who intervene, form alliances, display their own weaknesses. It's the judgement of Paris, after all, that has started this whole thing.

Hera, Athena, Aphrodite held a beauty contest and selected Paris as judge (not a very pleasant position for Paris to be in). The goddesses tried to bribe Paris; Aphrodite offered him Helen, the loveliest woman in the world, and Paris gave Aphrodite the apple signifying that she was the most beautiful.

Now the problems begin: 1) Helen is married, so she must be kidnapped from the Greeks; 2) Hera and Athena are ticked off! So battle lines are drawn in the heavens and on earth.

For all its scope, the epic centers around the basic human problem of feeling wronged and trying to atone for guilt. The Greeks really have been wronged by the interference of Aphrodite and the lust of Paris. Achilles is wronged when his prize (yes, captured women were prizes then) is taken from him by the head of the Greek troops. Achilles is wrong not to help his comrades, and he is transformed into a heartless animal when he drags Hector's corpse behind his chariot as revenge for the death of Patrocles.

The world of these ancient powers, of the gods and goddesses, of powerful nations is out of balance. The turmoil parallels the imbalance of Achilles who has lost his reason--he mopes and plots revenge and rages.

Students are often surprised not to find the Trojan Horse in this book. That story is told as a flashback in The Odyssey; it's an example of Odysseus's cleverness.

This book ends before the Trojan war is over. It is over when Achilles's wins his own emotional war. The book ends with his recognition of a father's pain; the last lines reveal that he is restored to humanity and community as he lets Priam, the Trojan, the enemy, bury his son:

They piled up the grave-barrow and went away, and thereafter

assembled in a fair gathering and held a glorious

feast within the house of Priam, king under God's hand.

Such was the burial of Hektor, breaker of horses. (172)

![[schedule]](butsked.gif)

![[discussion questions]](butdisc.gif)

![[writing assignments]](butpaper.gif)

![[readings]](butread.gif)

![[home]](buthome.gif)