adding brains to brawn

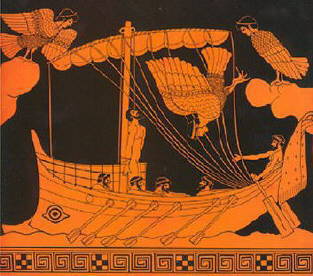

So many writers and filmmakers have paid homage to Homer's The Odyssey. There are, of course, the straight film renderings of the epic, but there are also more modern works that have taken the central ideas and patterns of the epic and reworked the material for modern audiences: James Joyce's Ulysses, William Saroyan's The Human Comedy, Nikos Kazantzakis's The Odyssey: a Modern Sequal, Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the recent Coen brothers' O Brother, Where Art Thou?

Homer's epic works on two levels; it's really two stories--a story of Odysseus's wanderings (adventure, danger, temptation, triumph), and a story of the restoration of a marriage and a home and a kingdom.

It's about beating the odds and, in the process, living life to the fullest. Unlike the often bitter and brutal world of The Iliad, where the hero Achilles alternates from brooding to raging, The Odyssey is about facing challenges and using human gifts (with a little help from the gods and goddesses every so often) to solve even the most extreme problems. Achilles is characterized by martial superiority; Odysseus is characterized by cleverness.

The ruse of the Trojan horse was Odysseus's idea. Stuck on the plain before Troy for years, it appears as though the Greeks will never defeat the Trojans. Pretending to be defeated, the Greeks sail off leaving behind a giant wooden horse as a tribute to the winning Trojans. The Trojans wheel the horse into the city and feast and drink and dance until they are exhausted. Late at night, the belly of the horse swings open; some Greek soldiers creep out and open the gates of Troy; the Greek fleet sneaks back ashore and the armies storm the city. Troy falls. In the end all of Achilles's strength does not win the war; Odysseus's cleverness does.

In addition to intellect, Odysseus is classically strong (he strings the massive bow at the end of the book when none of the usurpers can budge it). He has passion and energy. Above all, he loves life.

Here is the books's opening from our text:

Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story

of that man skilled in all ways of contending

the wanderer, harried for years on end,

after he plundered the stronghold

on the proud height of Troy.

He saw the townlands

and learned the minds of many distant men,

and weathered many bitter nights and days

in his deep heart at sea, while he fought only

to save his life (67)

Loving life is one thing, but all of Odysseus's shipmates die on the return trip. He often openly sacrifices some men so that others might live. Some readers might think this a bit selfish; what sort of leader would preserve his life at the cost of the community (that hardly agrees with the Greek notion that the community always takes precedence over the original)?

But really it's a quirk of our text that give us this impression. The opening (not included in our text) says more than this man fought only to save his own life:

...while he fought only

to save his life and to bring his

shipmates home.

He may not have controlled the fate (fate and luck and games of chance figure largely in this book) of his men, but he tried to save them, often from their own foolishness. For all its death, the book is a celebration of life. Late in his wanderings Odysseus descends into the underworld where he sees the great Achilles:

'But was there ever a man more blest by fortune

than you, Akhilleus? Can there ever be?

We ranked you with immortals in your lifetime,

we Argives did, and here your power is royal

among the dead men's shades. Think, then, Akhilleus:

you need not be so pained by death.'

To this

he answered swiftly:

'Let me hear no smooth talk

of death from you, Odysseus, light of councils.

Better, I say, to break sod as a farm hand

for some poor country man, on iron rations,

than to lord it over all the exhausted dead.' (241)

The wanderings of Odysseus (my interpretation)

Homer, borrowing from legends and tales popular in his time, used some familiar, some imagined, background locations for The Odyssey. I'm certainly not old enough to say "yes" or "no" that the epic is based on fact, but some of the settings are places around the Mediterranean that would have been familiar to Greeks 2800 years ago. Based on internal evidence and popular tradition, I've put together a fairly reasonable route for Odysseus's journey. There are other WEB sites you can visit that have other maps you might want to see, and although there are differences, many of the locations are very similar from map to map.

- The "A" (alpha) on the map indicates the best-guess location of Troy (in current-day Turkey)

Kikones (the cannibal race) was somewhere near Thrace; this gives us some insight into how the Greeks viewed their neighbors

The Land of the Lotus Eaters is likely on the coast of what is now Libya

The Cyclops on the island of Sicily where history (?) tells us there was a giant race (some scholars put the cave of Polyphemus on the west coast of mainland Italy, but the land description is more consistent with Sicily)

Aiolia (Island of Winds) was likely the Lipari Islands off the toe of Italy (based on internal information of navigation and weather)

Lastrygonians (here I'm stumped; there are two logical candidates) on the west coast of Italy (based on the description of Odysseus sailing east from Aiolia) -or- in northern Europe (based on the description of the Land of the Midnight Sun)

Circe on Aiaia Island (west coast of Italy not far from Rome; this is based on popular legend)

Hades in the North Pole (!?) (based on geographic description)

Sirens on the Prowling Rocks, the Planctae Islands (this was a shipping hazard, but it was tempting to sailors because it was a shortcut; ships were often destroyed on the rocks)

Scylla & Charybdis were likely in the Strait of Messina (another dangerous shortcut with sharp rocks on one side and turbulent waters on the other)

Cattle of Helios at Thrinakia on Sicily (based on navigation description in the story)

Calypso on Ogygia near the Strait of Gibralter (again, based on the navigation description in the story)

Phaecians were on Scheria (now Corfu; this is a historical location)

The Omega on the map represents the end of Odysseus's journey on the isle of Ithaca (Leucas Island) off the west coast of mainland Greece

Did a Greek commander take his shipmates through years of storm-driven adventures trying to return from a war against Troy? There is really nothing to suggest that any of the events of The Odyssey were litrally, historically true. But it's reasonable to assume that even the most fantastical works of literature are grounded, somehow, in the real world.

![[schedule]](butsked.gif)

![[discussion questions]](butdisc.gif)

![[writing assignments]](butpaper.gif)

![[readings]](butread.gif)

![[home]](buthome.gif)