first a quick timeline

A lot happens between the fall of the Roman Empire and the Rise of the Holy Roman Empire; here's a brief list of events leading up to and through the middle-ages (approximately 500-1500 A.D.):

(31 B.C. - 180 A.D.) - The Roman empire is floursihing

(32 A.D.) - Death of Christ; Peter becomes the "rock" of the Church; Christianity goes underground for about 400 years

(400's A.D.) - The Dark Ages; Germanic tribes invade and complete the dismantling of the Roman empire

(early 500's A.D.) - Europe becomes Christianized; Athenian philosophy schools founded by Plato are closed

(570 - 632 A.D.) - Mohammed; the Koran is transcribed 633 A.D.

(590 - 604 A.D.) - Pope Gregory establishes the temporal power of the Roman Catholic Church and institutes the Gregorian calendar

(700's A.D.) - Norse/Saxon/Danish conquests of England and France; the Heroic period

(1000's A.D.) - Rise in Norman French power

(1096 - 1099 A.D.) - The first Crusade for the Holy Land fought between Christians and Moslems

(1100's A.D.) - German and French romances

(1200's A.D.) - The gothic arch flourishes

(1300's A.D.) - The travels of Marco Polo open up new trade routes and new cultural contacts

(1311 A.D.) - Corpus Christi feast is established; plays are used to introduce Biblical material to the masses

(1320's A.D.) - Dante's Divine Comedy

(mid-1300's - 1400's A.D.) - Chaucer, Boccaccio, later romances; the Black Death wipes out much of Europe

(later 1400's and beyond) - The age of exploration which will eventually usher in the Renaissance

so much hinges on the middle ages

Although there is not a lot being written during the earlier centuries represented on this sketchy timeline (which is why these are called the Dark Ages--because the lack of information makes them dark to historians, not because they had little lighting), it's clear that Christianity was changing the nature of Europe. From a relatively secretive collection of followers and disciples scattered about the Mediterranean countries, Christianity became an increasingly powerful religious and political force; by Dante's time, it was the dominant force.

As much as people complain about the (real) violence of the Church Militant and the corruption that was often found in the huge Church Politic, the Christian Church did manage to civilize (with all of the positive and negative connotations that word may contain) a much larger empire than even the Romans imagined.

The message was that people should be heaven-centered, not earth-centered. The means of spreading the message were twofold: accomodation and intimidation.

If the Church were to move to an area where the popular religious customs somewhat paralleled orthodox Christian rituals, the native customs would be absorbed. For example, when people put Christmas trees decorated with lights and tinsel and colored baubles in their living rooms, they are re-creating the Western European custom of lighting a yule log (a pagan custom) which encourages the sun to find its way back to earth as the days grew darker and colder during the winter months. The eggs and bunnies associated with Easter are pagan fertility symbols (what once represented the rebirth of crops became a symbol of the rebirth of the spirit).

If the local people were intractable, then battles would break out. Violence may not be in keeping with the message of Christianity, but it was accepted by as a means of expanding the Church, unifying people, establishing order, saving souls. This may seem terribly ironic, and many are inclined to cast stones at the growing Church, but look around the planet before the rise of Christianity, and look again these days; much of the conflict comes from all-too-human followers of various pacifistic religions.

By the way, the violence and corruption is not lost on Dante (whose vision of the meaning of church doctrine and dogma is a fair reflection of the orthodox view of the time) who places several Church officials, including corrupt popes, in various circles of hell.

If the messangers were sometimes weak, the message was still clear: the things of the world can be dangerous distractions that blind an individual to spiritual growth. It's not a novel message; most major religions have much the same lesson just as they have some form of golden rule: "treat others the way you would like them to treat you."

And in his Divine Comedy Dante gives us an elaborate allegory (though some have taken it quite literally) of the sorts of things that derail humans from the right path and the consequences for being off or on "the way."

Before looking closely at a few cantos of the epic, it's a good idea to get a general appreciation (an overview) of the work.

It's packed with symbolism!

There is the numeric structure of the work (lots of threes, thirty-three cantos times three books plus one extra canto to round the epic out to one-hundred--considered to be a numeric representation of perfection)

The circles and bolges contain punishments that symbolize the crimes (sins) committed--more on that later

The geography of hell and purgatory trace spirals (circles, cycles, perfection), and the trip through heaven moves increasingly toward the light along the dance or music of the spheres/planets)

The story involves characters from three different kinds of sources

Mythology (familiar stories from Greek and Roman antiquity that paralleled the sin or virtue being discussed; by the way, note how partial the Italian Dante is to Roman characters--he selects Virgil as his guide--and how the Greek figures are often villified)

The Bible (again, his readers would all be familiar with the stories from both the Old and the New Testaments)

History/Politics (a lot of the characters in the books are people Dante knew, and he again shows his bias by softening the treatment of those people from the real world he liked and heaping hardship and torture on those he didn't)

It's a comedy (?) Comedy in this case does not mean funny (though some parts of the book are funny). It referred to an unusual stylistic blending that Dante incorporated in the book

Formal, carefully-crafted cantos with richly-textured poetry and sublime comparisons

Common (for the time) vernacular sections with grim, graphic, sometimes even coarse detail; comedy meant common, and this is an unusual feature for a book about such lofty matters as eternal damnation or salvation of the soul. It's this mix, along with the mix of characters and literary references, that gives the book it's broad appeal and shows the depth of its application

The logic of hell (purgatory, heaven) in the book(s) is fairly straightforward: sin is punished in a means appropriate to that sin; virtue is rewarded in a way that parallels the virtue. As I said, it's possible to take the Divine Comedy absolutely literally (people who commit adultery are chained to boulders that are whipped around in darkened caverns), but it's more logical to examine the work allegorically (the adulterous sinners are chained to the unyielding weight of their own tempest-tossed emotions, doomed to the earthly sight of their earthly lovers but unable to break through to a more magnificent vision of God).

The sinners in Inferno are in hell not just for their behavior; they have consciously willed themselves into hell. "Consciously" may be a bit strong; some cases suggest "given into" is a better description. As the poets wind their ways into the narrower, deeper, more horrific circles of hell, they move from the regions where people give into animal urges (lust, anger) that mainly affect the sinner, to areas where the sinner has manipulated others (simple malice, fraud); finally, the coldest and darkest areas of hell are reserved for the crimes that show cold-hearted calculation such as betrayal (at the very bottom of hell, Satan in encased in the ice that symbolizes the coldness of his treason).

By the way, we certainly are not required to agree with Dante, but his "punishment fits the crime" motif is fairly logical on many levels. The work can even be read psychologically (for example, people steeped in rage maneuver themselves into situations of rage).

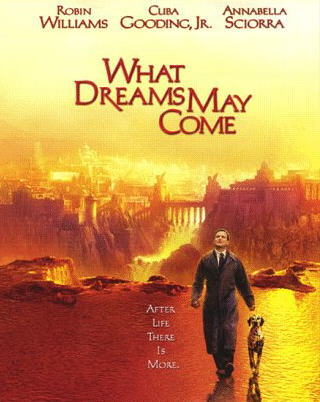

Why a person would willfully place him/herself in hell is a bit mystifying, but for a modern interpretation of this concept read Richard Mathesson's What Dreams may Come or rent the movie starring Robin Williams, Annabella Sciorra and Cuba Gooding, Jr. The movie's a bit long-winded in spots, but at its heart is the idea that one ends up on hell by willfulness, total immersion in some material obsession, giving in, giving up, despair.

-- continued in next week's lecture

![[schedule]](butsked.gif)

![[discussion questions]](butdisc.gif)

![[writing assignments]](butpaper.gif)

![[readings]](butread.gif)

![[home]](buthome.gif)